CULVER CITY, Calif.—Actor/director Tim Robbins is known for his longstanding social commitments through theatre and film. For the past 37 years he has directed The Actors’ Gang, and much of his work with the company has expressed a progressive outlook on the world.

So it is with The New Colossus.

“I live in Los Angeles,” Robbins says, “where one can only be struck by the contributions made to our city by immigrants and people who came here as refugees. The Actors’ Gang felt compelled to respond to the government’s anti-refugee and anti-immigration policies—and to tell a story that draws attention to the true nature of people that live in this country. Save for the Native Americans, all of our families came here as refugees, immigrants or slaves. The characters in the piece all seem different, from different parts of the world, traveling at different times—but the stories are remarkably the same: the common experience of all refugees is that they are fleeing some kind of oppression and moving toward safety and hopefully, freedom. Our hope is that we will be able to illuminate the courage, fortitude and humor of all refugees, and, perhaps, our own family.”

The New Colossus is, as many readers know, the title of a sonnet written by Jewish American poet Emma Lazarus in 1883 for an exhibit to raise funds for the pedestal for the Statue of Liberty, which opened in 1886. Even though the Statue of Liberty was not conceived as a symbol of immigration as such, the poem, written just as a massive new wave of immigrants started pouring into our expanding country, reconceived the statue’s purpose, turning Liberty into a “mother of exiles,” a symbol of hope to the outcasts and oppressed of the world:

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

According to the printed program, workshopping The New Colossus began two years ago, in the midst of the Syrian refugees crisis, when all that Americans could seem to think about was the potential for terrorists to infiltrate the refugee ranks. The United States ended taking in far fewer, both in absolute numbers and in proportion to our population, than many other advanced nations with adequate resources to accept them.

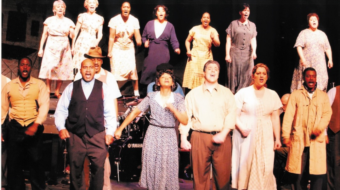

The 90-minute intermissionless production is as much about physical movement as it is about the use of words to tell its story. Twelve actors relate their ancestors’ journeys out of oppression, often employing the languages of their homeland. The evening is accompanied by live music performed by a cellist (Mikala Schmitz) and a percussionist/guitarist (David Robbins).

People who share no common language often turn to signaling and mime. The New Colossus affirms the common humanity of all by means of gesture and movement when words fail. Multiply twelve actors by 90 minutes of constant movement, and you have thousands and thousands of gestures which no single pair of eyes can take in comprehensively.

The babble of voices, often piled on top of each others, is incomprehensible except as a composite portrait of refugees. The New Colossus is better seen not as a play as such, but a pantomime pageant, a mural, a mosaic of where we came from as a nation. At least in part: for not everyone arrived to these shores or across our borders as a refugee—many others came for family reunification or for educational, professional or economic opportunity.

Still others, such as the play’s representation of Sadie Duncan by Quonta Beasley, tell of enforced African-American enslavement in Louisiana, post-Civil War Ku Klux Klan terrorism, and escape. That was a welcome complement to the cast, but otherwise, unfortunately, there was no example of refugees from the African continent.

The twelve actors, and their characters, three men and nine women, are as follows:

Pierre Adeli, playing his father Homeyun Dideban (Iran)

Onur Alpsen, his close friend Mehmet Fatih Tras (Turkey)

Quonta Beasley, her great-great-great-aunt Sadie Duncan, with added research on the Reconstruction Era (Louisiana)

Kayla Blake, her mother Anna Margaret Wong (Borneo)

Kathryn Cecelia Carner, her great-grandmother Elin Matilda Nylund (Finland)

Jeanette Rothschild Horn, her grandmother Yetta Rothschild (Germany)

Dora Kiss, her grandmother Aranka Markus (Hungary)

Stephanie Lee, Ly My Dung, based on her mother and grandmother (Vietnam)

Mary Eileen O’Donnell, Helga Schmidt, based on research (Austria)

Zivko Petkovic, his grandfather Mirko Petkovic (Yugoslavia)

Mashka Wolfe, her mother Tatyana Iosifovna Birger (Soviet Union)

Paulette Zubata, her mother’s friend Gabriela Mia Garcia (Mexico)

Incidentally, the initial promotion for this play mentioned 15 refugees from 15 countries, but in the course of production these numbers were obviously pared down. Missing from the final lineup are Italy, Chechnya, Spain, Japan, Ireland and Sweden.

The actors each carried a small to medium-size suitcase and were dressed in items of clothing that suggested their origin. In separate units of the presentation, they identified themselves by name, age, country of birth and the year they became a refugee. Each said some parting words of love, encouragement or warning to their loved ones left behind. They mentioned the primary causes of their problems in the home country: a petition signed, religious theocracy, no work, shortages, re-education camps, prison, the Klan, police, terror. They said what they did professionally—teacher, seamstress, engineer, baby nurse, art student, acrobat—and what they remember and miss from home. Their movements were silent interpretations of packing, washing, opening and closing doors, always with a fearful eye toward discovery or arrest.

And lots of walking. As actors learn in their first-year classes, along with their mime exercises, there are many kinds of walking—crouching, creeping, shuffling, skipping, striding, stooping, ducking, marching, running, fleeing, all the while moaning, crying out, sighing, breathing heavily. The 90 minutes turn into one big actors’ workshop on all the elements that go into the refugee theme: crossing a fence, fording a stream, keeping warm by a fire, drinking from various water sources, escaping the attention of overhead planes, hiding from gunshots, shivering from the cold.

Although the movements of the twelve performers are specifically choreographed, sometimes emphasizing their apartness, at other times showing them moving as a pack, there is little interaction among the characters. An argument might break out, but about what we can’t tell because each spoke their own language. Someone might sing a nostalgic song of their homeland, someone crying might be comforted by another. A troubling bug or rodent is found in someone’s coat. People tell a story or a funny anecdote, but no one understands.

Once, the group comes together to shout and wave, trying to call the attention of a passing ship or truck.

Curiously, despite certain longueurs such as the scenes huddling around the water and the fire, there is also a lot missing from the show. No one smokes, no one eats, no one sleeps or collapses from fatigue. No one is toting a child, no one is traveling with a spouse or friend, no one lightens their burden by tossing a heavy item away, no one relieves themselves.

Also absent: Explanations, or even a hint of how our own U.S. policy created some of the conditions refugees are fleeing. That certainly was the case with those running from the chaos in Syria, and how about Iran, Vietnam, Mexico, Germany and elsewhere?

Watching this docu-theatre unfold felt at times like peering into a microscope and seeing a colony of cells agitating randomly across the specimen glass. No developed characters emerge, so it is almost impossible to emotionally bond with anyone in particular, just the collective aggregate, faces in a crowd, similar to the projections of “huddled masses” throughout the performance.

Ultimately, we are prompted to ask, Who are we as a nation right now? Where do we come from? What values moved us to get here, and which ones hold us together? Are we still indeed the “mother of exiles?”

After the performance, the cast and the director conduct an open discussion with the audience, inviting them to share their stories or their families’ stories as refugees or immigrants.

The theme is highly important and contemporary, the staging somewhat academic.

The New Colossus plays Thurs., Fri. and Sat. at 8 pm through March 24 at the Ivy Substation, 9070 Venice Blvd., Culver City 90232. For more information and tickets call (310) 838-4264. Thursdays are pay what you can nights.