The recent Supreme Court decision on the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) addressed the most pressing, immediate issue facing Indigenous children and Tribal sovereignty, but it left some serious loopholes. The important point is that it left the ICWA intact, while not addressing a number of important questions, which is par for the course for the American judicial system in regard to Indigenous nations. U.S. law is largely chaotic in regard to Indigenous peoples.

It has been best described by prominent ACLU attorney Steven L. Pevar in the introduction to his book The Rights of Indians and Tribes, where he stated:

“The subject of Indian rights is complex and terribly confusing. There are tens of thousands of treaties, statutes, executive orders, court decisions, and agency rulings that play integral roles. Indian law is a subject unto itself, having few parallels.”

Adding to the confusion is the just-issued Supreme Court decision on Navajo water rights. The Court ruled, in a legal sleight-of-hand decision, that the United States does not have to provide access to water for the Navajo Nation. What makes this confusing? Long-established federal Indian law under the Winters Doctrine, known by a case of the same name decided in 1908 in which the Court ruled that Congress has the power to reserve water for federal lands, and by implication exercises that power every time it creates an Indigenous reservation.

The Winters Doctrine, also known as the “implied reservation of water” doctrine, has been without exception upheld, for over a hundred years, in case after case, by the Supreme Court—until now. This has been the law in treaties, statutes, and executive orders irrespective of whether water was mentioned or not. Indigenous reservations are created by Congress with the intention of making them livable, habitable, and productive, and whatever water is necessary to realize these objectives is reserved by implication for tribal use.

It is the duty of the Court to carry out this Congressional mandate. Further, all of the enactments creating reservations must be interpreted liberally in favor of the tribal nations. Here again, we have justices who either don’t know the long-established canons of federal Indian law or have elected to ignore them for political considerations.

Another way

That said, this article delves into an area of political discourse that is much more straightforward—Marxism and the National Question—and its relationship and relevance to the Indigenous nations of the United States. What follows is by no means exhaustive of the subject, for that would require a treatise in itself, but it will touch upon some of the more salient points as a starting reference for future reflection.

V.I. Lenin famously said of Czarist Russia in the early 19th century that the regime was “the prison house of nations.” This so aptly applies to the relationship of the federal government to the 574 Indigenous nations within the borders of the United States.

Native nations have limited internal sovereignty and no external sovereignty and are subject to the tyrannical rule of Congress under the dictatorial concept of plenary power. This simply means that Congress can do whatever it wants, whenever it wants, up to and including legally dissolving the very existence of any given Indigenous nation. What stands in the way of such draconian measures is the political strength of the Indigenous movement and international oversight.

This plenary power was referenced by Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett in her ICWA opinion, although in a way that ironically held at bay the racist challenges to the Act. Nonetheless, plenary power remains the rule of insufferable tyranny.

For centuries, the legitimate sovereignty of the Indigenous peoples has been ruthlessly suppressed, confining tribal nations in a virtual political jailhouse of national and racial oppression under the thumb of a capitalist oligarchy quite similar to the tyrannical autocracy of Czarist Russia prior to the October Revolution. The parallels are unmistakable.

The environmental racism of the pipelines crossing tribal treaty lands, racist police harassment of tribal citizens, racist imposed poverty levels, deadly health issues, racist imprisonment of tribal members, the threatened existence of Native languages, and corporate robbery of reservation resources—all of which are tied into the suppression of tribal sovereignty which should not be repressed under the generally-accepted principles of international law.

All of the above is amplified by the successful struggle to defeat the racist attacks on ICWA. The lack of the free exercise of Indigenous sovereignty is one of the hallmarks of the “prison house of nations” to which Native peoples are subjected by the imperialist government of the United States.

The right of nations to self-determination

Lenin spoke of the “right of nations to self-determination,” up to and including the right of secession. Under U.S. capitalism, the sovereign rights of Native peoples and nations were brutally and genocidally suppressed from the very inception of the United States right up to the present day. In Czarist Russia, the same political situation obtained until the October Revolution. There are so many parallels between Czarist Russia and the U.S. system in relation to oppressed nationalities that only the most salient shall be touched on in this article.

The same brutal history of domination was the lot of both the Indigenous peoples of the U.S. and the peoples of Czarist Russia and in particular those of the Central Asian Republics and Siberia. In particular, the Russian invasion, conquest, and colonization of Siberia with its multiplicity of Indigenous peoples has been compared to the European invasion of the present-day United States.

The Siberian peoples resisted the Czarist incursions with a martial response reminiscent of the Indigenous wars that raged in the U.S., a prime example being the Chukchi conflict of the 18th century. Similarly, as in the Americas, the Czarist forces conducted a campaign of genocide, calling for the Native people to be “totally extirpated.” These campaigns were pursued with mass slaughters the same as in the U.S.

Some nationalities were literally wiped out, while others experienced an 80% population decline due to introduced diseases such as smallpox. Again, this is another parallel to what happened to Indigenous peoples in the U.S.

Lenin led the resistance in Russia and, aware of this historical legacy, foresaw that the success of the revolution depended upon the unity of the working class with the long-oppressed nationalities.

Lenin led the resistance in Russia and, aware of this historical legacy, foresaw that the success of the revolution depended upon the unity of the working class with the long-oppressed nationalities.

In Czarist Russia, there were nomadic peoples in Siberia who had their own identity and had not reached the stage of nationhood. There were different levels of economic development and, as a result, various levels of national consciousness. Many of the nationalities had no written language.

In his stellar work, The Right of Nations to Self-Determination, Lenin addressed the oppressed European nations and nationalities. But in Czarist Russia, Lenin further developed Marxist theory to deal with the many peoples who were at differing and lesser stages of national growth. These included nomadic nationalities who lacked a broad centralized authority.

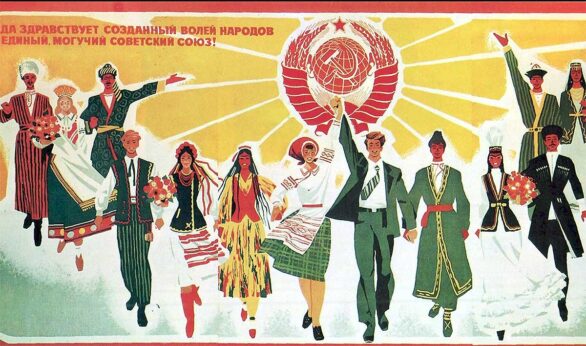

The Soviet government embraced the Leninist concept of national self-determination, allowing these many nations, nationalities, and peoples to develop various forms of nation-state development. The Soviet government formed with the voluntary consent of the differing peoples—the rise of socialist nations, fully sovereign—with the right to secede if they so desired.

Looking to the Soviet experience

It must also be noted that the National Question is a class question and an integral part of the struggle for socialism. The concept of self-determination is a class weapon in the arsenal of the proletariat. Under the Soviet state, all of the former subject peoples of Czarism proceeded on the path of national-state development in various forms. At its height, the USSR was composed of 15 sovereign Union Republics and included 20 Autonomous Republics, eight Autonomous Regions, and ten National Districts. All of these formations were free until the overthrow of the Soviet Union in December 1991.

With no available and reliable data on the current state of the Central Asian Republics and Siberia and the restoration of capitalism in the former USSR, it can only be assumed that the peoples of those geographic entities are once more the subjects of national and racial oppression.

As of late, there are reports that the Russian forces fighting in Ukraine are largely composed of national minorities. An account from the Buryat Republic states that for every “Moscow region” soldier killed, 625 Buryat soldiers have lost their lives. Another Buryat spokesperson said “genocide” was being committed, with his people being used as cannon fodder. It is unclear whether the Buryat soldiers were volunteers or conscripts. Consequently, this article will only address the National Question while the Soviet system was extant.

Under Czarism, the peoples of these republics were the victims of brutal domination and hideous exploitation by the regime and their own homegrown bourgeoisie, where such existed. Lenin realized that Marxist theory had to pose the issue of national determination in a new way to meet the demands of the times. Following his leadership, the emergent Soviet state realized the need for the development of the peoples along national-state lines. The National Question in Russia was extremely complicated.

The path of the liberation of the formerly oppressed nationalities, of 200 distinct peoples each with their own language, traditions, and culture, was started upon post-haste with the rise of the USSR and was begun by the issuance of decrees that were put into immediate action by the elimination, in fact with concrete measures being taken, of all oppression that had been the lot of these toiling masses. The Bolsheviks actively fought all forms of oppression.

The right of self-determination was not just an afterthought or a last-minute measure after the revolution. Even prior to the October Socialist Revolution, the Bolsheviks held that the Right for Self-Determination was an all-important condition for the success of the revolution and the future development of the socialist state. This demand was set out in 1903. In fact, the Bolsheviks in 1915, led by Lenin, were the very first to demand that this right be available to all the nations of the world.

Immediately following the revolution, the Soviet state began implementing the principles of national-state development laid out by Lenin. The national self-consciousness of the non-Russian populations was promoted and encouraged. Each officially recognized ethnic population, no matter how small, was granted its own national territory where it exercised autonomy with national schools and the development of national leadership.

A written national language was crafted, national language preservation and planning, a native-language press, the training of native teachers, the formation of national theaters and literature written in the native language, along with the national territory was a constituent part of social, political, and economic development.

The advancement of formerly nationally and racially oppressed peoples was unheard of in the annals of world records. The rapidity with which living standards were raised, medical advances achieved, illiteracy wiped out, and poverty erased is unparalleled in the history of humanity.

There was also a great emphasis placed on language rights. This began with the right of children to be taught in their own native language and the use of Indigenous tongues in the national administrations of the various peoples.

The national cultures of all the formerly nationally and racially oppressed peoples flourished as never before in the Soviet state. There were schools with courses in the different Indigenous languages and literature prolifically produced in the Central Asian and Indigenous Siberian tongues.

Another foundation of Soviet state policy was the Declaration of the Rights of the Peoples of Russia, adopted by the Soviet government in November 1917, immediately after the October Revolution, which recognized the sovereignty and equality of all the distinct peoples of the former Czarist empire. This recognized the right of free self-determination. The promptness with which this right was enacted and recognized attests to the importance of this measure to the Bolsheviks and to the sincerity and seriousness with which it was done. It was a concrete step with far-reaching consequences.

During the Soviet years, this policy produced many gifted writers, poets, artists, and actors from among the Central Asian and Siberian nationalities and peoples.

Tearing down the prison house

Contrast this with the continued national and racial oppression of Indigenous nations in the United States. The U.S. has long been the bedrock home of racism, the foremost exponent of worldwide oppression.

But in a socialist America, there would be an exponential development of Indigenous life. The Native peoples would decide their own destinies, with full sovereignty available to be chosen. The Soviet model of national-state development, in all its diverse forms, could be studied for ideas. The Leninist principle of voluntary consent with the right of self-determination is a major one.

The prison house of Indigenous nations in the U.S. would be torn down and full national sovereign development realized. The reservations could function as truly independent countries with full sovereignty. It’s a future to work toward.

As with all op-eds published by People’s World, this article reflects the opinions of its author.

Comments