DETROIT—Sara, a part-time community organizer for a non-profit here, often treats her depressive symptoms—intense sadness and anxiety, insomnia, irritability, and decreased interest in her prior hobbies—as well as her head and stomach aches with incense, crystals, herbal teas, bath bombs, and meditation.

Sara had a lot of past trauma, which often manifests itself in thoughts of suicide and sometimes actual attempts, but she considers therapy out of the question. She says she has neither the time nor the money to get into treatment. She spends most nights at an art studio she rents with other local artists, and she would have to consider drastic lifestyle changes to make relief through psychotherapy a possibility in her life. So she’s left with the choice: Take any “free” time and excess funds and put it all into years of therapy, or enjoy her passions in that “free” time. The view supposedly popular among the young healthy set today is clear: If she opts for the latter, she’s being selfish and not working hard enough to “fix” herself to succeed.

Situations like Sara’s provide an ever-increasing market for novel “mental health” remedies today. Nearly 60% of adults with mental health concerns do not seek treatment. The costs for mental health care are cited by many as the biggest deterrent. Most of those who don’t pursue care but who’d like to do so say it’s simply too expensive. Prescription costs alone for psychiatric medications are all over the place, ranging from an extra $4 to hundreds of dollars per month, depending on what works best.

“Finding the right medication for someone may take several trials and dose adjustments. The best treatment is individualized to the person, and this can be time consuming,” says Dr. Flavio Casoy, a public psychiatrist in New York City. Most workers don’t have sick leave for weekly therapy and treatment, and attaining good mental health care is requires a major time commitment.

Addiction treatment costs are even higher. For example, the National Institute on Drug Abuse estimated in 2017 that the cost of methadone was $4,700 yearly; standard inpatient addiction treatment facilities can cost between $14,000 and $27,000 for a 30-day program.

But the costs that deter people from getting treatment are far less than the costs that eventually come from untreated mental illness: Average hospital bills for readmitted patients with mood disorders is $7,100. The human toll is even higher. In 2019 alone, there were over 70,000 drug overdose deaths in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nearly 50,000 Americans died by suicide last year, according to American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. How many of them were related to untreated mental illness?

Mental health novelty: Goop and “wellness” products

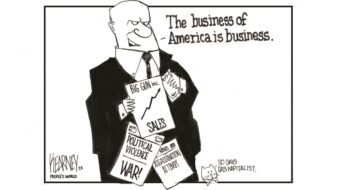

In a capitalist economy where no “need” or want goes unfulfilled if there is a profit to be made, it’s no surprise that “wellness”—a new marketable substitute to costly mental health care—has flourished recently. “Mental health” and wellness are becoming synonymous with more affordable alternatives to expensive medical practices and medications. It’s a market estimated in 2020 to be valued at $4.5 trillion. The new treatments on offer are things like yoga, meditation, “mindfulness,” and pseudo-spiritualist products and services.

Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop “Wellness Shop,” for example, offers for sale a wide selection of products for better diets, beauty, “the art of sleep,” style, and even traveling. Across the internet, there is no shortage of advice columns and lists for ways to relax and reduce anxiety. There are classes for “grounding” or “centering” oneself. You can buy endless amounts of candles, crystals, teas, incense, supplements, light masks, or acupuncture kits to help you on your “wellness journey.”

Paltrow is far from the only one capitalizing on the acute shortage of affordable mental health care. Wellness stores—from crystal peddlers to herb shops—are popping up everywhere. Retailers Neiman Marcus and Anthropologie have opened up their own branded wellness lines, relating one’s health with one’s fashion. Mobile apps, like HealthJourneys, teach people to breathe and relax via guided meditation, so long as they pay monthly subscription fees.

Such “wellness products” are actually within reach to working-class people like Sara, unlike expensive and time-consuming therapy and medication. Considering their novelty, they seem to be much easier and more accessible solutions to health problems than confronting the uncertainties of illness.

Positivity and “self care” as medicine

The focus on “positivity” as medicine in lieu of real care plays into the capitalist culture’s myths: Sara is led to believe her lack of personal accountability is the primary cause of her “failure.” She believes that she herself fully caused all her mental health problems through her lack of the right attitude. The truth is that her recourse to self-treatment in the marketplace is actually due to her inability to access the health system itself.

In the final analysis, concerns of mental health get boiled down to the market logic of today: They put the responsibility for success or failure fully upon the individual. That is to say, the individual is the sole point of blame for any and all failures. “Health” is so often put into terms of how much one has “earned” or the “hard work” one has put into achieving it. “Self care” has become a buzzword that perpetuates the stigma around any mental illness by suggesting anything less than complete health and happiness is rooted in personal failure.

However, there are organizations across the nation, many working at the local level, that are putting in the work to bring awareness and more affordable services to the mental health world. Michigan Mental Health Association, for example, advocates on a state level for funding for services for all who need them. In 2004, it drafted state law on open access to medications in the Medicaid program for mental illness—the type of work it carries on to this day. This author is one of many volunteers who have personally worked with the Association to conduct seminars on suicide and mental illnesses, as well as help write legislation to propose to the state.

The danger with the growth of the wellness market, which treats people in need of mental health care as potential customers rather than patients, is that the focus on struggles at the local and state levels will fade, and our collective health will be another thing we try to repress.

It’s hard not to empathize with Sara when she complains how hard it is to stay positive.

Comments