LOS ANGELES — Western (i.e., Caucasian) artists have a seemingly irrepressible urge to fetishize, generalize, and stereotype all other cultures and people—Indigenous peoples, Asians, Latinos/as, Africans—and even some now regarded as “white” but who were once “othered” such as Italians, Irish and Jews.

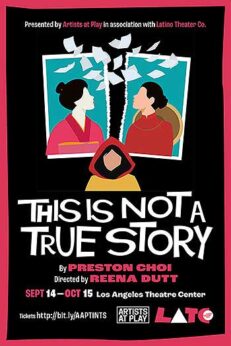

Artists at Play, in association with Latino Theater Company, is currently staging the world premiere of This Is Not a True Story, written by Preston Choi and directed by Reena Dutt. The long one-acter is a full-frontal examination of anti-Asian racism in blatantly Orientalist works that uses surrealist hilarity and preposterousness to tackle the often implicit, invisible prejudices theatrical audiences are so accustomed to seeing and loving, never realizing how hurtful they are.

Artists at Play, in association with Latino Theater Company, is currently staging the world premiere of This Is Not a True Story, written by Preston Choi and directed by Reena Dutt. The long one-acter is a full-frontal examination of anti-Asian racism in blatantly Orientalist works that uses surrealist hilarity and preposterousness to tackle the often implicit, invisible prejudices theatrical audiences are so accustomed to seeing and loving, never realizing how hurtful they are.

At the same time, the play raises the intriguing question of what might ensue if some of the fictional characters we accept as seminal to our understanding of the world come to life as real people. After seeing the play (Sept. 21) it occurred to me that the current runaway success of Greta Gerwig’s film Barbie owes in great part to that conceit as well. Is this the start of a new thematic vogue?

The play is set in some kind of Orientalist purgatory, where three Asian “tragic heroines” are forced to reenact their woeful deaths over and over again, almost as if every time someone in the world sees Madame Butterfly, for example—and that could be 3000 people in a big opera house for any given performance—poor CioCio San in eternity must reenact her suicide by hari-kari, bidding farewell to her Japanese-American son as she chooses to die with honor rather than live in shame. The enthusiastic sound of audience applause is blasted into the theater—hundreds of thousands, millions of operagoers expressing appreciation for this iconic death scene. The looping doesn’t become tiresome, as it might on film, because this is live theater and there are always some amusing variations. Also, if she strays too much from the word-for-word retelling of the story, a manly voiceover like some satanic stage director tells her, “That is not in the script” or “That is not your line.”

I am reminded of the mordant joke about Bono, the world-famous singer-songwriter, global activist, and philanthropist, appearing in an African relief concert in Israel. “Every time I clap my hands,” he says, doing so at two-second intervals, “a child in Africa dies of hunger.” A voice rises up from the audience, saying, “So stop clapping!”

CioCio (Julia Cho) is one of the three characters subject to tired old racist tropes about romantically doomed women unable to control their fate as their white male lovers who desert them escape guilt-free. The other two are Kim from Miss Saigon (Zandi De Jesus) and Kumiko/Takako from the 2015 film Kumiko the Treasure Hunter (Rosie Narasaki).

Only once they meet in this literary purgatory and compare notes can they begin to reclaim their human agency and break the cycle to which they’ve been condemned. Learning for the first time to read and write, they can alter their futures in scripts of their own making. “Why am I rhyming my trauma?” Kim is finally able to ask.

“Preston has created a hilarious and nuanced take on how the Asian heroine has been historically represented on stage and screen,” says director Reena Dutt. “Theatergoers will never again look at Madame Butterfly or Miss Saigon the same way. Through the comedy that ensues from CioCio and Kim’s self-revelations, it’s a surprise to find out Kumiko’s truths considering she’s based on a real person, Takako Konishi, who was unfortunately misrepresented in film. Who knows, maybe CioCio and Kim were based on real people who were twisted as well?”

Madame Butterfly, the opera house standard by Italian composer Giacomo Puccini, is the story of Cio-Cio San, a 15-year-old Japanese geisha (the soprano). She gives up everything, including her religion, becoming nominally Christian, to marry American naval officer B.F. Pinkerton (the tenor). The American, part of a naval visit to start “opening” Japan up to Western investment and trade, is a heartless cad who by the second act has abandoned her and their young son, considering his “marriage” to the child-woman (do we smell a pedophile here?) an exotic, non-American sham of no legality.

The opera is based on the play Madame Butterfly: A Tragedy of Japan by David Belasco (1853-1931), which he adapted from John Luther Long’s 1898 short story “Madame Butterfly.” Some scholars have suggested that the original story might have been based on an actual incident. Belasco’s play premiered in 1900, and Puccini saw a production of it in London later that year. The play and the short story served as the basis for the libretto of his 1904 opera. Belasco was the San Francisco-born son of Sephardic Jews, and must have been conscious of the powerful push for Jews—like his tragic heroine—to convert, change their names, and disappear into the great American melting pot.

Miss Saigon (1989) is the world-renowned musical (by composers Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil, with lyrics by Boublil and Richard Maltby Jr.) based on the opera. Kim is a beautiful 17-year-old orphaned Vietnamese bar girl in love with an American G.I. who abandons her during the fall of Saigon, leaving their son Tam behind. The play’s Kim is completely taken aback when she’s finally convinced that her very life is nothing but a reincarnation of a Japanese girl invented by an Italian composer and impersonated by countless generations of middle-aged operatic divas. Curiously, the most successful performers in the role of Kim have been Filipinas (including here), which itself may be a telling commentary about the history of the U.S. occupying the Philippines and regularly intervening in its affairs. “I actually grew up with that show since I was 10 years old,” said De Jesus in the talkback after the play. “I didn’t understand what was so wrong with [it].”

The title character in Kumiko the Treasure Hunter is based on an urban legend about a real-life person, Takako Konishi, who was found dead after traveling from Japan to North Dakota. According to the myth, Konishi believed that the Coen Brothers film Fargo was a true story and went looking for buried cash. The real story was much grimmer: Takako went to Fargo, a place she had previously visited with her former married American lover, to commit suicide by freezing to death after losing her job following 9/11. As a character in the play, she recognizes she is at least partly true and partly fictional, unlike her new friends CioCio and Kim, who are both characters invented by European men. “I chose to kill myself,” she says proudly, while the other two were written to kill themselves.

“I wanted to search for the more well-rounded people underneath these stereotypical, suicidal Asian women, all written by White men,” explains Choi. “Critiquing racist tropes in a fun, dark way weakens their power so that they can’t haunt us as before.”

Snippets of recognizable arias and songs stream through the production, reminding the audience just how universalized—and beloved—this brand of Orientalism has become.

Anti-Orientalists have always wondered if the problems in these works couldn’t be resolved by underscoring Western imperialism more, to show not just how racially “doomed” the Asian women are but how invasion, occupation, oppression, discrimination, war, rape, pillage, and genocide necessarily dominate the script. That would entail actual resistance on the Asian side, however, and basically a new script with an anti-imperialist ending. The new Beijing operas developed by Madame Mao and her circle during the Cultural Revolution in China did exactly that. “Dying made me important,” CioCio says. “They didn’t care about me when I was alive.” What if upon Pinkerton’s return to Nagasaki three years later, with his American wife Kate, CioCio skewered his guts with her father’s suicide knife instead of her own?

The creative team for This Is Not a True Story includes scenic designer Yuki Izumihara; lighting designer Henry Tran; sound designer M. Glenn Schuster; projections designer Vanessa D. Fernandez; costume designer Jojo Siu; props designer Naomi Kasahara; and dialect coach Kurt Sanchez Kanazawa. Katherine Chou serves as both associate director and dramaturg. The stage manager is Yaesol Jeong.

Audiences are invited to laugh at the exaggerated “traditional” stage accents assumed by the three characters. It’s one of the delights of the play to hear how the actresses flit back and forth between their role accents, their conversational accents as their characters, and their “real-life” accents; and turn on a dime between the histrionic performance of their endlessly repeating death scenes, their more casual action (still as their characters) in the underworld present, and then in the emerging consciousness of themselves as natural human beings liberated from the scripted page. The imaginative staging is especially playful: A big part of it has to do with how babies appear and what happens to them.

This Is Not a True Story plays on Thurs., Fri., and Sat. at 8 p.m. and Sun. at 4 p.m. through October 15. The Los Angeles Theatre Center is located at 514 S. Spring St., Los Angeles 90013. For more information and to purchase tickets, call (213) 489-0994 or go to www.latinotheaterco.org.