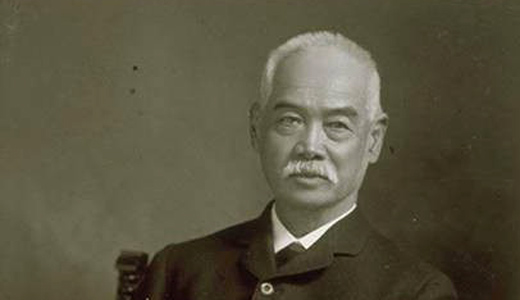

Educational pioneer Yung Wing (1828-1912) worked to bridge cultural gaps between the U.S. and China. He came to America under the sponsorship of a missionary and received his degree from Yale in 1854, making him the first Chinese student to graduate from a U.S. university.

We honor his achievements in connection with Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, which takes place each May, celebrating the culture, traditions, and history of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the United States.

In June 1977 Reps. Frank Horton (N.Y.) and Norman Y. Mineta (Calif.) introduced a resolution to proclaim the first ten days of May as Asian-Pacific Heritage Week. (During World War II the Mineta family was interned for several years in the Heart Mountain internment camp near Cody, Wy., along with thousands of other Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans.)

A similar bill was introduced in the Senate a month later by Daniel Inouye and Spark Matsunaga, both from the state of Hawaii. (Inouye fought in World War II as part of the famous 442nd Infantry Regiment, lost his right arm to a grenade wound and received several military decorations. Matsunaga became a U.S. Army Reservist in 1941, volunteered for active duty in July that year, and was twice wounded in battle while serving with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and the 100th Infantry Battalion.)

The month of May was chosen to commemorate the immigration of the first Japanese to the United States on May 7, 1843, and to mark the anniversary of the completion of the transcontinental railroad on May 10, 1869. The majority of the workers who laid the tracks were Chinese immigrants. President Jimmy Carter signed a joint resolution for the celebration on October 5, 1978.

In 1990, George H.W. Bush signed a bill passed by Congress to extend Asian-American Heritage Week to a month.

During this month, communities celebrate the achievements and contributions of Asian and Pacific Americans with community festivals, government-sponsored activities, museum exhibitions and educational activities for students.

Pioneer, reformer, refugee

Born in 1828, Yung Wing grew up in poverty near Macau, a Portuguese colony in China. He attended missionary schools there and in British-owned Hong Kong. (Both Macau and Hong Kong are now part of China.) When Rev. Samuel Robbins Brown, the headmaster of the school in Hong Kong, returned to the U.S. in 1847, he brought Wing and two other students with him.

Yung Wing lived with the Brown family and attended Monson Academy in western Massachusetts. In 1850, he enrolled in Yale College and just two years later became a U.S. citizen. In 1854 Wing earned his B.A. from Yale. Although other Chinese students had attended U.S. universities by this time, Wing was the first to graduate from one.

Wing maintained ties to China, hoping to modernize its technological infrastructure by educating its future leaders in New England. In 1872, in Hartford, he established The Chinese Education Mission (CEM) and soon after married Avon (Conn.) resident Mary Kellogg. He lobbied the Chinese government to establish a program allowing Chinese students to study overseas. The program sent 120 Chinese boys to the U.S. over a four-year period. Wing returned to the U.S. to oversee the program’s implementation.

Deteriorating diplomatic relations led to the Mission’s demise, however, and to Yung Wing’s removal to China. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 dealt his dream an abrupt and final blow. For its part, the Chinese government itself had concerns about the influences of Western culture on their students.

Wing and the students of the CEM returned to China years earlier than they had originally intended. An enthusiastic supporter of reform in China, Yung Wing found his life in danger after an 1898 coup d’état created a backlash against reformers in that country. The new government placed a $70,000 bounty on his head, and Wing fled Shanghai for Hong Kong. He appealed to the U.S. government to allow him back into America, but received notification that his citizenship had been revoked. Through the help of friends, Wing managed to illegally sneak back into the United States. He lived out his remaining years in poverty in Hartford, and died in 1912.

Sources: ConnecticutHistory.org. A earlier version of this article appeared in People’s World on May 21, 2015.

Photo: Yung Wing, Hartford, circa 1900. Connecticut Historical Society.

Comments