Co-chaired by Rev. William J. Barber II and Liz Theoharis, the Poor People’s Campaign began in May 2018 with 40 days of coordinated action at statehouses across the U.S. to confront systemic racism, poverty, ecological devastation, militarism, and the war economy.

Now mobilizing for a massive June 18th “Mass Poor People’s and Low Wage Workers’ Assembly,” today’s Poor People’s Campaign is reviving the work of the original Poor People’s Campaign led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1968.

Billed as a “moral march on Washington and to the polls” for the November elections, the event next weekend will target lawmakers and push them to address what the Poor People’s Campaign calls the “moral, economic, and political crisis” facing the nation.

From the west coast to the east and at all points in between, people are signing up for spots on buses and joining in the organizing. And they’re bringing co-workers, family, friends, and neighbors with them to the nation’s capital. The massive march will occur, appropriately, on Juneteenth weekend, which celebrates the democratic revolution that ended slavery and established Black Reconstruction in the South.

The original Poor People’s Campaign was the last big effort led by King before his assassination, the capstone to all his work on behalf of the racially and economically oppressed. King was instrumental in bringing together the labor and civil rights coalition that defeated key planks of the Jim Crow counterrevolution after Reconstruction. Then, as now, the forces of democracy and the extreme right were in sharp confrontation.

When King declared, “I have a dream!” to more than a quarter-million people in D.C. in August 1963, KKK and police terror in Alabama was still a fresh wound. As many as 1,000 children in Birmingham had walked out of school the previous May to protest segregation, only to be greeted with fire hoses, police dogs, batons, and arrests. But that action forced the Birmingham Truce Agreement, a set of anti-segregationist measures, followed by white supremacist bombings, civil unrest, and heavy repression.

“We have…come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now,” King declared then. “Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy.”

The current Poor People’s Campaign says it’s that time again. Today’s demands have echoes of the past.

By the time of King’s 1963 speech, President John F. Kennedy had already been pushed to propose the Civil Rights Act. But it was blocked by a filibuster in the Senate. By November—three months after the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), NAACP, United Auto Workers (UAW), Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and other civil rights and labor organizations had gathered along the Lincoln Memorial reflecting pools—Kennedy had been assassinated.

Nonetheless, one year later, the movement behind King won the Civil Rights Act and anti-poverty “Great Society” legislation. In August 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act. But ten days before pen was put to paper launching the War on Poverty, Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, escalating the U.S.’ war on Vietnam. That’s when King increasingly began to highlight the connection between racism, poverty, and militarism.

“It seemed as if there was a real promise of hope for the poor, both Black and white, through the poverty program,” he said in 1967. “Then came the buildup in Vietnam, and I watched this program broken and eviscerated.”

In November 1967, King announced the Poor People’s Campaign, with a plan to descend on Washington the following May. The campaign demanded $30 billion for a program of full employment, guaranteed income, and more low-income housing.

Four weeks before the scheduled mobilization, King was assassinated in Memphis. He was there for a march with mainly Black sanitation workers, striking against unequal wages and working conditions after a horrific incident in which two sanitation workers were crushed to death.

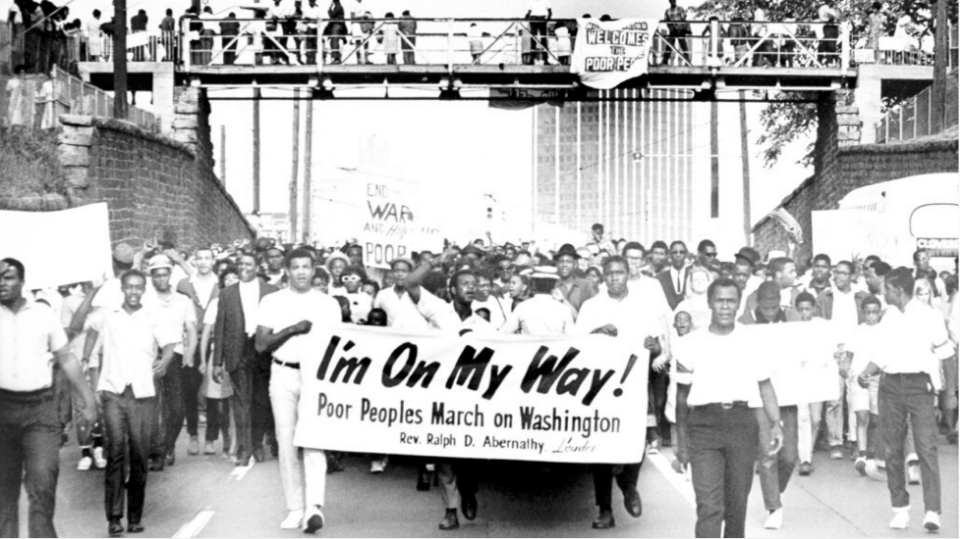

The movement mourned, but it pushed forward. The Poor People’s Campaign carried on under the leadership of King’s successor at the SCLC, Rev. Ralph Abernathy.

Corretta Scott King led a Mother’s Day protest in D.C., beginning two weeks of demonstrations for an Economic Bill of Rights. A six-week tent encampment named “Resurrection City” was built on the national mall. The UAW brought 80 busloads out for the 50,000-strong protests on “Solidarity Day,” held on June 19th—Juneteenth.

On June 4th, as thousands occupied the national mall, Robert Kennedy, the candidate most aligned with the civil rights movement, won the California Democratic Party primary. Later that night, he was shot and killed. Twenty days later, over one thousand police came to the national mall to evict Resurrection City, arresting hundreds of people. Six months later, the ultra-right forces behind Nixon, who railed in his campaign against “rioters” and promised more policing and to protect segregated schooling, would come to power following the November elections.

Four decades later, organized labor and civil rights organizations across the country united to elect the nation’s first Black president, Barack Obama. What followed was both the racist Tea Party reaction that gridlocked Congress in 2010 and brought Trump to power six years later.

But a broad labor and left-wing struggle also arose to push a democratic agenda forward—from Occupy Wall Street in 2011 and the #Fightfor15 and a Union to Black Lives Matter, the 2017 Women’s March, and more recent fights to defend abortion rights. LGBTQ equality struggles have escalated, especially in defense of trans people, and a new rising militancy in the labor movement, increasingly led by young workers, is pushing forward union drives across the ountry. The small-d democratic and socialist-oriented electoral struggles that supported Bernie Sanders, AOC, and Stacey Abrams are a part of that mass democratic movement, too.

That’s the context for today’s Poor People’s Campaign.

Its leaders come by their activism naturally. Barber was born two days after the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. His parents moved to North Carolina when he was in kindergarten to participate with the school desegregation movement, and he’s been a fighter ever since. The church he pastors, Greenleaf Christian Church Disciples of Christ, is a “123-year-old congregation founded by former slaves.”

“If you follow the James River from this city down to the sea, you will find the place where my African American ancestors first set foot on these shores,” Barber told marchers in Richmond, Va., in 2016 for the Fight for $15 convention. They were in “the capital of the former Confederacy,” he reminded the crowd.

Behind him loomed a statue of Robert E. Lee statue, since removed and cut up in pieces after the enormous 2021 Black Lives Matter demonstrations. “My African American ancestors were brought here to work the land, to build this nation, but they were paid nothing for their labor.”

He spoke of the reversal of the democratic gains of Black Reconstruction after the Civil War: “When African Americans served in the Southern legislatures for the first time, they built a movement with poor whites. … They rewrote the constitutions of every southern state,” and “banned work without pay, demanded equal protection under the law … This wasn’t in the 1960s, this was in the 1860s!” Barber noted that they wrote into those constitutions the right “to the enjoyment of the fruit of your labor.”

“They knew that labor without living wages was nothing but a pseudo form of slavery.”

Theoharis began her activism in college fighting homelessness in Philadelphia after moving there from her hometown of Milwaukee. As a student she became involved in a group called Empty the Shelters, a local affiliate of the National Union of the Homeless. After leading the establishment of the Kairos Center for Religions, Rights, and Social Justice, together with Barber she became a co-chair of the Poor People’s Campaign in 2017.

“We cannot return to normal,” Theoharis wrote in a statement to President Trump and Congress amid the early days of the COVID-19 emergency. “This is not the time for trickle-down solutions. We know that when you lift from the bottom, everybody rises. There are concrete solutions to this immediate crisis and the longer term illnesses we have been battling for months, years, and decades before,” she said.

“We will continue to organize and build power until you meet these demands. Many millions of us have been hurting for far too long. We will not be silent anymore.”

The massive mobilization in Washington, D.C., on June 18th will be proof of that refusal to remain silent.

Join the CPUSA’s “500-Strong” Delegation in D.C. on June 18th. Sign up here.

Comments