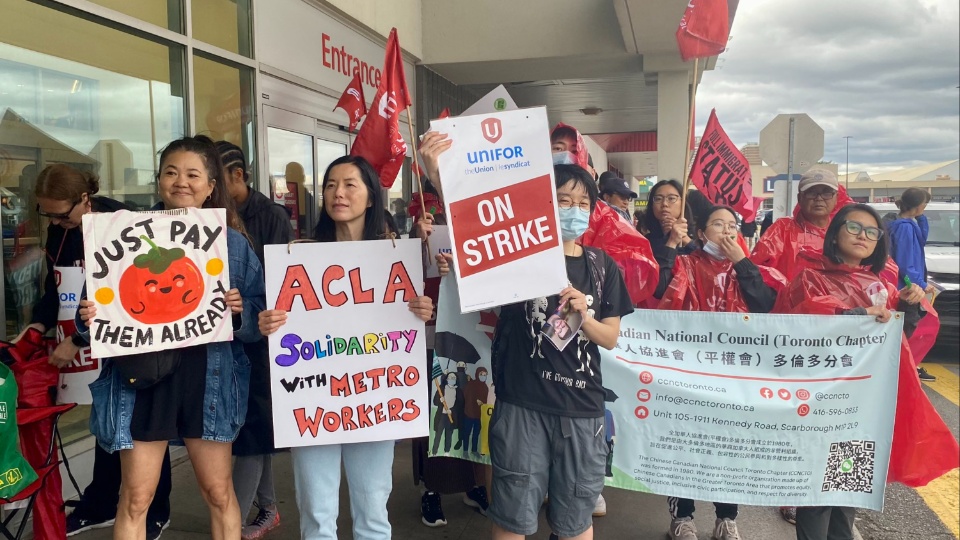

TORONTO—Striking grocery workers in Toronto and surrounding suburbs say they cannot afford to shop at the very stores they work in.

The 2,300 workers at 27 Metro grocery stores have been on strike since July 29, having turned down a tentative collective agreement that had been unanimously approved by their union leadership.

“I can’t afford to shop here, it’s true. And they don’t give us an employee discount either,” said one employee on a picket line at a north end Toronto store. Metro is a mainstream grocery store, not a high-end store like Whole Foods, but that sentiment has been echoed by many strikers.

The head cashier, who did not want to give her name, said she buys most of her food goods at stores like Walmart or No Frills, a chain carrying mostly economical, no-name products.

Although the official inflation rate is reportedly below 3%, the inflation rate for food products, out of control since the start of the pandemic, is still over 9% and many items are out of reach for wage earners just trying to play catch up and earn a living wage.

Montréal-based Metro is one of three mega-corporations that have a monopoly hold on the Canadian food retail industry. Along with Loblaws and Sobeys, the “big three” own 60% of the market, with sales over $100 billion last year. They also exert significant control on the supply chain, which affects many independents.

Striking full-time employees earn on average just under $23 an hour while part timers, who make up 70% of Metro’s workforce, earn $16-17, just above Ontario’s $15.50 minimum wage. In the collective agreement rejected by the rank and file, the full-time rate was proposed to rise by $1.05 in the first year and 90 cents per year in the following three years of the four-year contract; part timers would see a 70 cent raise each year.

The cost of living in Toronto is higher than most metropolitan centers in North America. It’s estimated an hourly wage of $26 is the minimum needed to afford a one-bedroom apartment.

In the second quarter of 2023, Metro’s net earnings shot up 26% to $346.7 million from a year earlier, based on over $6 billion in sales from its grocery and drugstore chains. Its top five executives raked in over $13 million in salary and bonuses for 2022, so when their Metro negotiators were offering the people who stock the shelves and work the checkouts a spartan wage increase for their contract renewal this summer, employees were not impressed.

The rank and file sent their union leadership back to the bargaining table in a scenario not uncommon in labor history. An anonymous source inside the union admitted the workers’ demand for the reinstatement of hero pay seems to have caught union negotiators “off guard.” The leadership failed to read how resolute its rank and file felt.

In defying their leaders, are union members signaling the start of a more militant workforce in the private sector? Some analysts believe a victory for the union in this labor conflict “could embolden front-line employees in other sectors to advocate for their rights, thus potentially setting in motion a chain reaction that could reverberate across the entire retail industry.”

Paul White, a spokesperson at Unifor, told People’s World he believes “this is an interesting time for workers. They’re rightfully frustrated, especially in the grocery sector when you’re hearing about the wild profits” the corporations are raking in.

“There’s an increased level of militancy and worker power that we haven’t seen in some time and this is a really important time for unions to direct some of this energy. We’re seeing more and more workers are fighting back and demanding their fair share.”

The current strike is an impactful microcosm of the labor struggle for grocery workers across Canada. It represents the first in a series of negotiations over the next couple of years with thousands of unionized workers of the big three grocery chains.

These workers realize they’ve amassed a supply of goodwill from the public, having worked in what many during the pandemic would agree was a risk-filled environment, even with mandatory masking. They served on the front line of what was suddenly deemed at the start of the COVID pandemic an essential service.

The public and media were recognizing any and all front-line workers as “heroes” and recognition went beyond the healthcare sector. Grocery retail employers in Canada and the U.S. complied with public sentiment in the chaotic, early days of the pandemic in the Spring of 2020 when they introduced “hero pay.” In Canada, this resulted in a $2 hourly wage boost for most grocery workers.

These factors now carry weight when calculating the union’s bargaining power. Unifor refused to confirm but several workers on the line say reinstatement of the hero pay alone won’t be enough to halt the strike. They feel more empowered than they have in decades.

Proof of the new playing field is the recent negotiation, resulting in what Unifor National President Lana Payne had called “a milestone agreement,” with Metro offering wage increases significantly higher than what the union had experienced in the past. One union source labeled previous contract offers from Metro as “absolute minimal improvements for wages and benefits.

“The only reason (Metro) is offering this now is everyone fucking hates them. If they didn’t foresee they would get destroyed in the media, they wouldn’t be playing ball with us.”

Metro has stated in a recent letter addressed to workers, “We look forward to welcoming you back to our stores soon” but has canceled their health benefits for the duration of the strike and has started an ad campaign proclaiming “We’re open!” in reference to its 300 other stores in Canada. Those workers are either represented by different unions or are not unionized. Unifor is covering the workers’ benefits and providing strike pay, which is just a fraction of their regular paycheck.

Stephanie Bonk, communications manager for Metro, refused to answer questions from People’s World, sending a statement saying, “We would like to let you know that the proposed wage increases are above the inflation rate for 2023 and future increases are above the projected inflation rate.”

One picketing worker in a central Toronto store is not soothed by that claim. “I’m worried about inflation going higher again in the future and we’re stuck with 90 cents a year” for an agreement that goes until 2027.

Metro’s official line from day one of the strike claims, “The agreement with the union provided significant increases for employees in all four years of the agreement.” They evidently portray the annual 4% wage hike as “significant.”

The rank and file’s thumbs down on the contract may signal a newfound militancy in the labor movement after decades of setbacks. And reports of job shortages in the industry help give the union the upper hand.

Grocery workers have a long memory when it comes to the “hero” pay boost, which lasted about four months in the first half of 2020, the start of the pandemic when most businesses had shut down. In June 2020, when COVID’s first wave began to wane, the industry’s big three corporations simultaneously rescinded hero pay, admitting soon after they had consulted each other. The resulting uproar pressured the federal government to pass anti-wage-fixing legislation two years later.

Virtually all groceries rejected calls for its reinstatement, even when workers pleaded when the pandemic reared its head again, with the Omicron wave in early 2022. Ignored was the fact the work was more difficult during the pandemic, with more stringent cleaning requirements, and keeping shelves well stocked while the public would sometimes panic shop some items. (Who can forget the run on toilet paper?) Not to mention increased employee absenteeism from stress and illness during COVID, which left workers still on the job picking up the slack.

The union rejected a Metro request a week ago to appoint a provincial government mediator as a “typical pressure tactic,” according to a union source, who said they will hold out until the employer shows readiness to discuss genuine improvements to the contract offer.

Picket lines are “rock solid” so workers are confident holding out will elicit a better offer from Metro. One picketer confirmed that sentiment, refusing to put a time limit on the strike, saying, “We’re holding on, going strong.”

Unifor is Canada’s largest private sector union, with more than 315,000 members. It was formed in 2013 when the Canadian Auto Workers merged with other unions. The name is not an acronym, but a bilingual term signifying “a union for everyone” in English and “united” (unis) and “strong” (fort) in French. They hope this current battle will be a harbinger of things to come in the grocery industry as well as other parts of the private sector, where unions are picking up momentum.

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today. Thank you!

Comments