During the heyday of American trade unionism, the local, regional and national influence of the Teamsters Union loomed large. At its peak the union neared two million members largely in transportation, a strategically significant sector of the economy.

Additionally, prominent figures like Teamsters’ International President James R. Hoffa became larger than life personalities, often seen socializing with celebrities and movie stars. Newspaper, radio and TV interviews, as well as hostile Congressional hearings, for example, served to bolster Hoffa’s – and his lieutenants’ – reputations and influence.

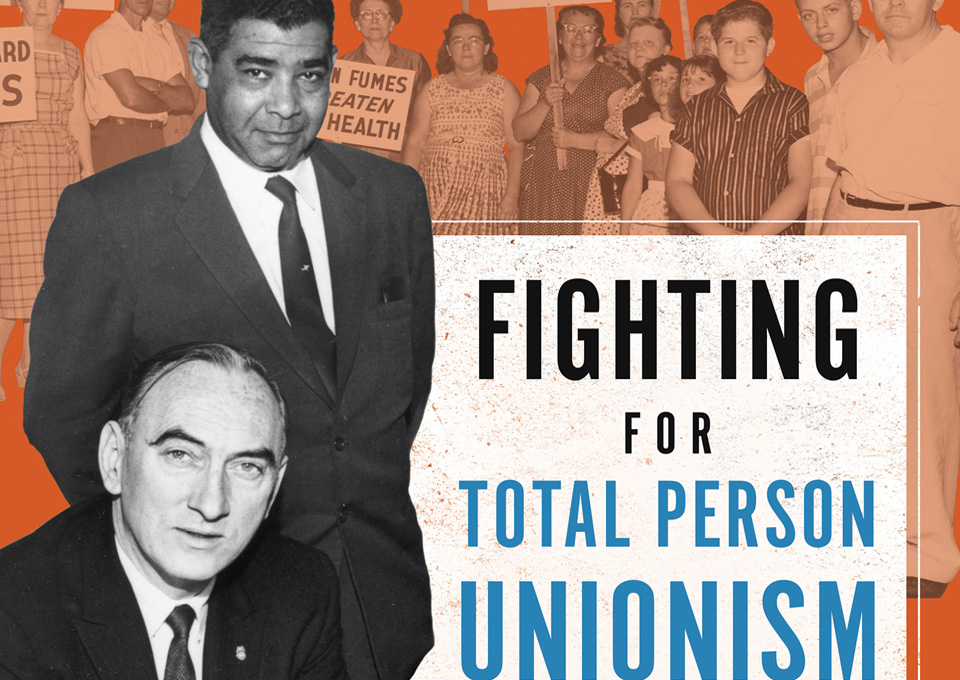

Interestingly, while the Teamsters’ commitment to and support for racial and gender equality was often spurious, especially on a national level, opportunities did emerge for local leaders to flex Teamsters’ muscle outside of the traditional confines of the workplace or contract. In fact, some local Teamsters, like St. Louis based Local 688 leaders, Harold Gibbons and Ernest Calloway, struck a delicate balance between a highly centralized, often undemocratic, mob-influenced union and an emerging, community-based, African American led civil rights movement, thereby articulating a type of civic trade unionism worthy of continued research and understanding.

Robert Bussel’s Fighting For Total Person Unionism: Harold Gibbons, Ernest Calloway, And Working Class Citizenship is a welcomed addition to our understanding of the Teamsters’ Union, two of its most important local leaders, Gibbons and Calloway, and the ever-changing dynamic of labor-community collaboration.

Both sons of working class miners, Gibbons was born into an Irish immigrant, working class family, while Calloway, was an African American one generation removed from slavery.

Arguably, their upbringing mirrored the experiences of many working class Americans raised during the Great Depression. However, while both Gibbons and Calloway articulated and fought for an expanded view of unionism, a total person unionism, they also made many compromises along the way, often mimicking the tactics of their patron, the Teamsters’ President, Hoffa.

In short, Gibbons and Calloway were simultaneously pragmatic and idealistic. They embodied many of the contradictions of a trade unionism struggling to gain legitimacy among business elites, while advocating for socialist-like programs initiated and administered by the union – programs that directly benefited the union’s membership, treating them as total persons, not just workers in a shop.

They dramatically expanded Local 688’s role into the sphere of civics, health, education and housing and created a community bargaining table, led by Teamsters and their allies, while unfortunately employing the internal, traditionally conservative, top-down, business union tactics that all too often disempowered rank-and-file union members.

Additionally, Gibbons and Calloway both held a special antipathy towards communists and the Communist Party, USA, often shortsightedly supporting center-right forces in an anti-communist crusade that not only harmed unions lead by communists, but also weakened the Teamsters at the community bargaining table.

Bussel does a great job humanizing both Gibbons and Calloway, providing personal depth of understanding and pragmatic political insight as these two remarkable trade union leaders attempted to construct a dynamic labor-community partnership demonstrating – in practice – the potential for an expanded, robust role for unions in the larger life of St. Louis’ majority Black population.

Unlike many other union leaders, Gibbons and Calloway championed African American participation in the Teamsters’ Union. As Bussel writes, “With a 10 to 15 percent African American membership…Gibbons sought to set an example within his own ranks, pursuing a multi-pronged approach to persuade his members that discrimination and intolerance were unacceptable.”

“The union sought to negotiate non-discrimination clauses in its contracts and succeeded in abolishing racially based pay differentials…the union also insisted in holding integrated recreational programs and social events. [Gibbons] recruited African Americans, Jews, and Asians for his staff…,” policies that often put Gibbins and Calloway at odds with their majority white, and often racist, membership.

Interestingly, Gibbons and Calloway’s efforts at constructing an inclusive, labor-community partnership meant that they usually had more in common with communist led unions – like District 8 of the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers’ Union lead by William Sentner, an open communist – than their AFL or CIO counterparts.

Additionally, Calloway’s leadership in the St. Louis NAACP provided Teamsters Local 688 access to African American community and business leaders, but also served to limit the union’s radicalism, placing it and Calloway at odds with the emerging Black Power Movement.

Later in life, as the political winds shifted and as the Teamsters International sought to consolidate power, Gibbons and Calloway were ousted. And their experiment in total person unionism was jettisoned by the union they had helped build.

Bussel paints a vivid portrait of two very complex – and often contradictory – union leaders. Fighting For Total Person Unionism: Harold Gibbons, Ernest Calloway, and Working Class Citizenship holds many important lessons for unionists today, and deserves to be read widely.

Fighting for Total Person Unionism: Harold Gibbons, Ernest Calloway, And Working Class Citizenship

By Robert Bussel

University of Illinois Press, 2015, 272 pages