ALEXANDRIA, Va.—In November, the state of Virginia and Amazon announced that the massive corporation is going to build huge headquarters centers in Alexandria and Arlington, just across the Potomac from Washington, D.C. A similar center will be built in New York City, and a smaller one in Nashville, Tenn.

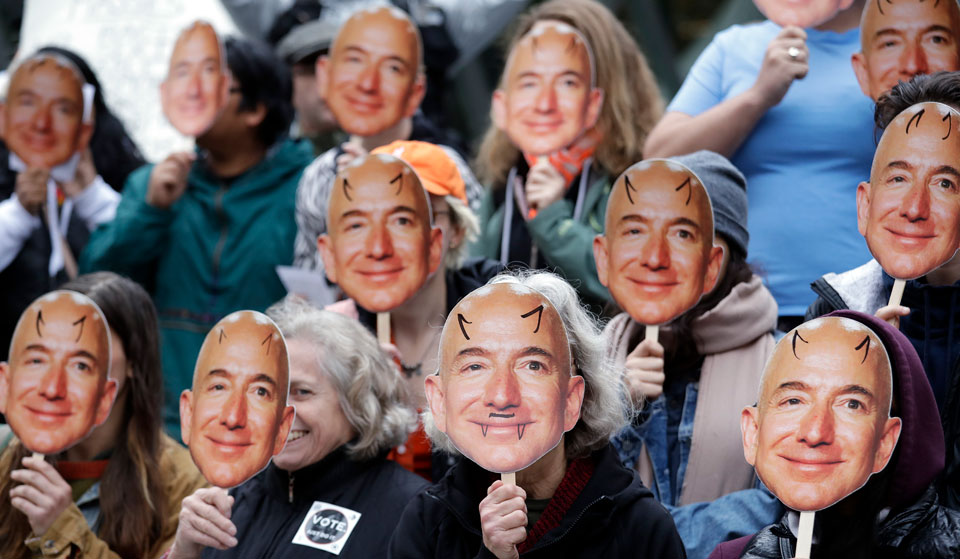

Various cities across North America had been bidding for these projects, in the usual way: Offering millions of dollars in “concessions” to Amazon, a company worth a trillion dollars, which registered $3 billion in net profits last year. Amazon’s founder and chief executive officer, Jeff Bezos, has a personal fortune estimated by Forbes at $124.8 billion, making him the richest person in the world by far, and by some calculations the wealthiest individual who has ever lived.

Bezos is also the owner of the Washington Post, the most influential newspaper in the D.C. metropolitan area. So Amazon has a built-in media support system for the project.

Local and state governments tout increased tax revenues and more “jobs” coming into the area as benefits from the Amazon move. Supposedly, New York and Metro Washington, D.C., will each see 25,000 new jobs created.

But in both New York and the Washington area, the coming of the new Amazon operations is seen as ominous by organizations and individuals working with low- and middle-income constituencies.

Besides the complaint that local governments negotiated the Amazon deal behind closed doors and without public input, the biggest worry is about skyrocketing housing costs and the probable displacement of large numbers of working-class families.

In the case of Washington and its Maryland and Virginia suburbs, the arrival of the Amazon headquarters project, called HQ2, comes on top of an existing pattern of severe increases in rental housing costs. By some calculations, renting a two-bedroom apartment in Washington itself may already cost over $30,000 per year and necessitate a household income of over $100,000.

A recent study by the Urban Institute serves as a warning to low-to-middle-income residents of the area on how such a project could affect them. The area encompassed in the study, Washington and its closest suburbs, has had a strong population increase in recent years, from 4.8 million in 2000 to 6.2 million in 2017. Unemployment is relatively low. So the Amazon project is not likely to provide jobs for existing residents of the area, but rather attract workers from outside. Without an increase in low- and moderate-income housing, this is certain to drive up housing costs, especially for rental units. This, in turn, will intensify an already existing dynamic whereby residents, especially renters, are pushed farther and farther away from Washington itself. This will mean longer commutes, and will greatly stress the area’s already problem-plagued public transportation system.

African-American and Latinx working-class residents especially already find themselves being pushed ever farther out from jobs and amenities near Washington, D.C., even as the overall Latinx population has increased.

The Urban Institute study cheerfully concludes, “Working together, the jurisdictions that make up our area have the capacity and resources to respond to accelerated job and population growth, strengthening the housing market so it better meets the needs of households across the income spectrum…. Whether they do so will go a long way toward determining whether we are building a prosperous and inclusive region for all our residents.”

Indeed. But what will motivate these varied jurisdictions to do the right thing, or to do anything at all, to offset the predicted jump in housing costs?

Those jurisdictions vied with each other, and with other cities, to attract Amazon—that’s why they were willing to use taxpayer money to make the concessions.

Local officials are shrugging their shoulders at the probable inflationary impact of HQ2 on rental housing costs, saying that these were rising anyway. Big business interests in the region trump those of low- and middle-income renters.

So if action is to be taken to counter the negative impact HQ2 is likely to have, it has to come from the base.

There are stirrings among local organizations. In the Chirilagua neighborhood in Alexandria, whose residents are largely immigrant families from Central America, the Amazon HQ2 project will be just down the street and is seen by community leaders as a looming menace. A local organization, Tenants and Workers United, based in Alexandria but with regional outreach, is raising the alarm. Tenants and Workers United has been very active in dealing with the issues that affect the population, which range from school quality, immigrants’ and workers’ rights to housing issues. Representatives of the organization are working to inform their neighbors of the danger of displacement caused by gentrification that the Amazon project is likely to cause unless action is taken.

At a Nov. 17 meeting of the County Board in Arlington County, just north of Alexandria, residents expressed annoyance at the secrecy whereby negotiations to bring in the Amazon project were carried out. Members of the Board responded that they had been minimally involved, and as yet had not seen some key documents on what exactly the state and Amazon agreed to. As County Attorney Steve MacIsaac put it, “the state has been very close to the vest on a lot of this stuff.”

Some residents were not having this. Evidently, Arlington itself had offered $51 million in incentives to bring Amazon in, without any public hearings. Tim Dempsey of the Our Revolution Arlington organization, one of several which showed up at the meeting, said, “We’ve come before this board on several occasions to express our concerns about the wisdom of incentive packages for large corporations and the potential negative impacts on the most vulnerable communities in our county.” What exactly will be done by the state, by Arlington, or by other local jurisdictions to offset the pressure on housing costs in the area remains a mystery.

In Virginia, the General Assembly must vote to approve the Amazon deal in February. Delegate Lee Carter, a Democrat and open socialist, represents a Northern Virginia district in the House of Delegates. Carter was elected in 2017, part of a Democratic wave that came within a millimeter of costing the Republican Party its majority in the chamber. He vows to play a leading role in fighting the impact of the Amazon HQ2 deal in 2019.

Carter points out that the hype put out by the deal’s promoters, that it is going to bring jobs into the area, is misleading. The “jobs” the project is supposed to create are not likely to go to needy local residents but will represent new employees coming into the area. This will create competition for housing, which will drive up the already high cost of housing. “It’s going to displace people out of their homes, and it’s going to make life quite a lot worse for quite a lot of people.”

There are legislative elections in Virginia in 2019, for all 100 members of the House of Delegates and all 40 members of the state Senate. Carter and others are hoping that the defects of the Amazon deal can be dealt with in that context. Whether a region-wide coalition strong enough to fight on this issue can be built remains to be seen.

Comments