Just in time for the holidays is a family movie that intertwines fun with a message targeting greed and capitalist monopoly. While the movie isn’t shouting “Down with the system!” from the chocolate rooftops, dominant themes throughout Wonka are the battle against corrupt wealthy businessmen and the plight of the poor. The new musical fantasy film that tells the origin story of the popular Willy Wonka character has good laughs, a relevant message, and a few memorable songs to boot.

Directed by Paul King, who co-wrote the screenplay with Simon Farnaby, Wonka shows the early days of Willy Wonka—a lead character in the 1964 novel Charlie and the Chocolate Factory by Roald Dahl—before he became a successful chocolatier.

Young Willy, an aspiring magician, inventor, and chocolatier, arrives in a European city to open a chocolate shop. The young idealist faces several challenges, though, not least of which is the “Chocolate Cartel” of greedy candy capitalists, who have law enforcement in their pockets. In addition, when seeking shelter on his first night in the city, Willy is forced into indentured servitude by a shady couple who trick working people into taking on huge amounts of debt in order to turn them into laborers.

From there, audiences are taken on a journey of Willy beating the odds with the help of the friends he finds along the way. The film manages to make the Wonka character relatable in a way that doesn’t necessarily require audiences to identify and sympathize with so-called rich “geniuses.” To understand the significance of this accomplishment, one must familiarize oneself with the original book and the much-loved 1971 film adaptation, Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory.

In the original book, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Wonka is a wealthy, successful chocolatier recluse. He had closed his factory three years before the events of the book due to his chocolate adversaries spying and attempting to steal his recipes. He eventually reopens the factory but with no workers from the city. His workforce is now made up of the mysterious Oompa Loompas—a race of people tiny in stature who seem entirely devoted and dependent on Wonka.

We learn in the book that, although Wonka is a genius inventor, many of his experiments have proven dangerous for the lives of the Oompa Loompas, on whom he tests his creations. Not to mention, the children whom he gives a tour of his factory after they each win a golden ticket are put in some deadly situations whenever they don’t behave. Wonka shows little sympathy when each child has a bad accident in the factory. He’s a genius looking for a potential morally sound heir to his business, but something sinister is mixed with his character.

When the 1971 adaptation came out, it was renamed Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, much to writer Dahl’s dismay. And when looking at the way he characterizes Wonka in the book, it becomes evident why he wouldn’t want to put more importance on Wonka over Charlie.

Charlie is a young working-class boy attempting to provide for his starving family (in the book, his father had been recently laid off from his job) and potentially help them financially. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory wasn’t about glorifying an eccentric millionaire with unconventional tendencies. One could argue that Gene Wilder’s performance as Wonka was a little too lovable (and, as writer Dahl once noted, lacked edge), as popular culture would come to elevate his character over that of the working-class Charlie.

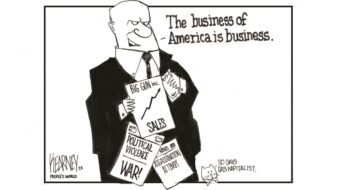

Although contemporary popular culture and corporate media have a tendency to put weird rich men on pedestals lately—think Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Mr. Beast, and Mark Zuckerberg, to name just a few—there’s also a reckoning emerging. Among many in the general public, increasingly rich people aren’t seen as ones to envy, but rather people want to know why they are allowed to hoard their wealth.

So how—in 2023, when the wealth gap is widening and many working people are demanding better from their employers—do you make an origin story about a future millionaire?

It would appear, as Wonka has, you make him the “Charlie” of his story. Emphasizing his working-class roots, his variety of friends who represent different aspects of working-class society, and you make his enemies the corrupt robber barons of the Chocolate Cartel. The result is a relevant and engaging story that makes you root for Willy as you pray for the downfall of the greedy capitalists.

Of course, this means the prequel takes liberties regarding Dahl’s original character, but it’s clear that it’s the only way this film can be as enjoyable as it is.

Timothée Chalamet does a fine job as the idealistic Willy. He conveys a Wonka who wants to share his chocolate with the world. He has dreams, ideas, and a lot of love in his heart. This Wonka doesn’t have an edge underneath but a naivete when it comes to the rough happenings in the world. He’s likable and welcoming. In this regard, he seems to channel Wilder’s Wonka more than Dahl’s book version. Yet, the film is an ensemble piece, as many characters bring the story to life.

Calah Lane as Noodle, an orphan girl who becomes Willy’s assistant, stands out in her performance. She’s even more of a Charlie-like character, as she’s lived a hard life, not knowing her real family and working for the shady couple to whom Wonka is also indentured. It also seems like a fitting nod that the young Lane is a Black actress, as Dahl’s widow gave an interview claiming that her late husband originally wanted Charlie to be a young Black boy in the book, but his publishers pushed back against the choice.

Paterson Joseph, Gerald Prodnose, and Mathew Baynton play the Chocolate Cartel that viewers will love to hate, just as much as the characters vocally admit to hating the poor. Joseph emerges as the most entertaining baddie as his villainous role of Arthur Slugworth exudes charm and menace with finesse.

Some viewers may hold the 1971 classic film (or even the Johnny Depp 2005 version) so dear that it’s hard to imagine a new story with a new kind of Willy. Yet, Wonka delivers a good installment with fun new characters in the Chocolate Factory lore. While Wilder’s film leaned more toward a morality tale against misbehaving children, Wonka takes aim at corruption by adults and businesspeople, which seems a lot more fitting given our current socio-political climate.

And while that is a heavy concept, Wonka remains fun and vibrant. The film is a few minutes short of two hours but never feels like it goes on for too long. Viewers will leave the theater possibly humming a new song after receiving a dose of positive reinforcement around the idea that greed does not benefit society. Wonka is an overall fun holiday treat.

Wonka is currently playing in theaters everywhere.

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today. Thank you!

Comments