WASHINGTON – “If we don’t tell our own story it will not be told,” says Dr. Frank Smith, founder and director of the African American Civil War Museum and Memorial here.

Regiments of African American soldiers, called at the time United States Colored Troops (USCT), were key in winning every major victory during the last two years of the Civil War. They captured Charleston, the cradle of secession, and Richmond, the capital of the confederacy. Yet their crucial role has been largely ignored.

According to Smith, writing black troops out of Civil War history helped lay the groundwork for almost 100 years of segregation and Jim Crow.

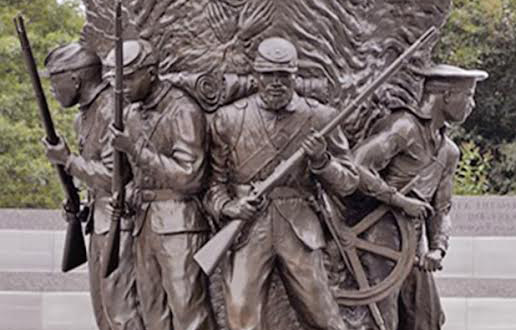

To this day, only two places in America are devoted exclusively to honoring the USCT: the Museum and the Memorial, which stand across the street from one another. The Memorial is a nine foot high sculpture called The Spirit of Freedom encircled on three sides by the Wall of Honor which shows the names of all who fought with the USCT.

“Without us, nobody would know who these soldiers were,” Smith says.

Three out of every four black soldiers in the Civil War had risked their lives to escape from slavery in order to risk their lives as soldiers fighting to end slavery altogether. They knew that the Confederacy had passed a law stating that all blacks captured in uniform would be treated not as prisoners of war, but as slave insurrectionists. The penalty was death.

Moreover, the Union Army barred blacks from becoming officers.

Despite all, close to 179,000 African Americans volunteered for the USCT. Nineteen thousand more were sailors. (Unlike the Army, the Navy was not segregated until Woodrow Wilson became president.)

Eighteen African American soldiers and five sailors won the Medal of Honor.

Banned from the Grand Review

Measures to remove from memory the victories of black regiments began thirteen days after the Civil War ended.

President Andrew Johnson staged a two day Grand Review of the Armies on May 23 and 24, 1865. All the armies of the Union paraded proudly down Washington, DC’s Pennsylvania Avenue to the cheers of ecstatic the crowds.

All the armies, that is, except for the regiments of the USCT. They were banned.

“This was a key event in American history,” Smith explains. “The whole nation saw no black soldiers, only pristine white troops. The message sent to both the white and black communities helped create the racial divide.”

To help counter the damage done long ago, this past May the African American Civil War Museum staged a re-enactment of the Grand Review as part of the sesquicentennial commemoration of the Civil War’s end. This time, black troops were front and center.

Black were not only banned from the celebration at the end of the War; they were also banned from the Union Army at the beginning.

“We are ready … to go.”

When the Civil War began, Frederick Douglass urged Lincoln to recruit blacks into the Army. He wrote: “We are ready and would go. … Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters, U.S., … and a musket on his shoulder … there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.”

But Lincoln would only allow blacks to be hired as ditch diggers and such like.

Even so, many African Americans were eager to fight. In 1862, blacks formed Union regiments in Louisiana, Kansas and South Carolina.

“As victims of brutal oppression, blacks had been de-humanized and humiliated,” Smith says. “Despite this, they took their lives in their hands and ran through deadly Southern territory to escape slavery and join the Union Army. After escaping, some even went back to their plantations and recruited others to join up.”

The official ban against blacks joining up ended almost two years into the War.

It became clear to Union generals that slave owners were forcing slaves to work for the Southern war effort. In response, Congress declared that it had become an “indispensable military necessity” to free enslaved persons. It passed a series of “confiscation” acts which contained the assumption that enslaved blacks were “property” but also that slaves in the South were war materiel and thus legitimate targets of confiscation.

In this way, Congress encouraged enslaved people in the South to join the Union Army. The regiments that had been formed previously became “official” and new fighting units were organized.

The last “confiscation” measure was an executive order, the Emancipation Proclamation. The War Department publicly authorized the recruiting of African Americans by establishing the Bureau of Colored Troops.

The tradition of fighting for freedom

Today, black families can learn whether or not their ancestors fought in the Union Army by using a computerized registry at the African American Civil War Museum.

One soldier in the registry, Caesar Cohen, is Michelle Obama’s great-great-grandfather.

If they want to do so, families can express their pride by making audio recordings through a program run jointly by the museum and the National Park Service.

Along with the registry, the museum has many ways to bring history alive. It showcases re-enactors and has displays of photographs, documents, and artifacts. The museum also sponsors lectures, seminars and special programs for students from pre-K to the 12th grade.

Smith says he got the idea for the museum and memorial when he was an organizer for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Mississippi. Local leaders who were risking their lives fighting to exercise their right to vote told him they were inspired by the fact that their grandfathers had been soldiers in the Civil War.

Several of these leaders had themselves been soldiers in World War II and had returned home determined to bring to Mississippi the freedom they had fought for in Europe.

Smith says that these leaders were following a tradition begun in the Civil War:

“Soldiers in USCT regiments had gone through the crucible of war,” Smith says. “They had mastered the weapons and skills they needed to defend their new-found freedom.”

For more information about the African American Civil War Museum and Memorial, go to www.afroamcivilwar.org.

Photo: Larry Rubin/PW

Comments