NEW YORK—Armed with Paul Bowles’s theatrical translation and a bust of Lenin for a prop, the New York Young Communist League (YCL) is reinvigorating Jean-Paul Sartre’s most renowned play with a distinctly red subtext.

No Exit (Huis Clos) is the French writer’s major contribution to the existentialist art movement. The one-act play observes three people trapped in a purgatorial afterlife, forced to contend with the mistakes they made in life that landed them together in a hell that denies them the satisfaction of the “fire and brimstone” cliché. No Exit contends with the cultural contradictions brought about by World War II through an up-close and personal exploration of its selfish, vindictive, and viciously self-conscious protagonists.

The YCL’s performance uses American author Paul Bowles’s translation, which was written less like a philosophical treatise and more like an actual stage script. After all, what originally popularized existentialism was not the work of academicians but Sartre’s play, which speaks directly to the uncertainty and grief left in the wake of the war’s atrocities.

Both Sartre and Bowles were of a communist persuasion, although their relationships to their respective countries’ communist parties were complicated. Nonetheless, their sympathies for radical thought can be found throughout their works, which reflect the debates among Marxists and anti-imperialists of their time.

Against the criticisms of many leftist philosophers, Sartre defended existentialism as an optimistic and humanist methodology that might actually complement Marxist theory.

Sartre famously wrote in No Exit that “Hell is other people”—but the larger argument contained within this phrase is that our conditions of existence, good or bad, heavenly or purgatorial, are what we make of them. Neither God, machines, nor money is the ultimate arbiter of our destiny. As humankind, we can and must rely on the possibilities contained within person-to-person relations to determine our futures. Comparatively, Marxist philosophy calls for the ultimate unification of the people in class struggle, against the shackles of individualism, isolation, and self-imposed exile from historical processes.

Thus, No Exit is ripe for a Marxist interpretation—and in fact, was originally written with this subtext. The New York YCL brought this subtext to the fore in both obvious and subtle ways. The imposing statue on the mantle representing the characters’ conception of hell is a bust of Lenin, leading the audience to wonder: perhaps what matters more than the judgment of God is the judgment of history itself. What might matter more is what we do to other people, rather than for an unidentifiable higher power, or even just ourselves.

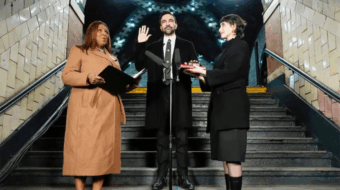

Chloé Stebenne (Inez), Nick Moseley (Cradeau), and Lizzy Wilburn (Estelle) bring an overarching compassion to their portrayals of No Exit‘s deeply flawed characters. The tone of Sartre’s Marxist humanism carries through in the intimate way Inez and Estelle fuss and fight over each other, and in the desperation in Cradeau’s voice as he defends his acts of cowardice. The final climactic eruption is as harrowing as it is cathartic, thanks to the slow buildup of emotion developed by the three actors throughout the play.

Meanwhile, the actors’ theoretical underpinning is the Bowles translation, which reveals a commitment to accessible and livable theatre—that is to say, art which can be enjoyed by everyone, regardless of education level or familiarity with existentialist philosophy. That the YCL chose this version, and explicitly paid homage to the translator in the play program, speaks to a similar artistic intentionality. The actors use this script to embody their characters as not just philosophical mouthpieces, but as free subjects, an idea integral to Sartre’s thought.

We have a lot to learn from No Exit today, especially when we embrace its radical origins through radical performance. Sartre’s idea of the free subject, rather than lionizing the liberal conception of the human individual, places a collective of people at the forefront of history-making. Sartre asserts that we are nothing but our lives and that participating in history is an active choice we must make again and again. The character of Cradeau attempts to escape history by crying pacifist in the face of Nazi occupation. Estelle rejects any commitment to her working-class background by marrying rich and seeking fleeting pleasures. And Inez manipulates her way into intimate relationships without regard for the human costs.

All three of these characters represent moral and social pitfalls we may all fall into if we become too jaded, too isolated. Sartre’s existentialism, rather than condemning humanity to a purgatory of apathy and disconnection, calls upon the audience to honor their commitment to other human beings and shape a radical future through action.

The unofficial motto of the YCL is “Education, Action, Recreation.” One of the primary ways young people build community connections is through cultural production, like music, theatre, and art. Why not infuse these practices with revolutionary politics? As was seen with the New York YCL’s performance of No Exit, which featured an after-party filled with discussion, books, and wine, the arts can create a foundation for organizing based on creativity and self-expression.

The Young Communist Leagues and other youth-led political organizations across the country should consider cultural activity and recreation an important part of their political work. It is a means for making political action fun, engaging, and welcoming for newcomers. When we engage with others across disciplines and in different cultural contexts, we deepen our understanding of each other and develop the kind of multifaceted solidarity necessary to produce effective, long-lasting organizing.

No Exit is directed by Nick Moseley and Gabe Gonzalez, with design by Kara Fan. Performance times are Sat. May 24th at 2:30 p.m. and 7 p.m. at 235 W. 23rd St., Manhattan, New York. Tickets are $10-20 at the door.