Across the globe, celebrations and exhibitions are marking the 100th anniversary of the birth of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo (1907–1954). In recent years, her popularity has soared to that of cult-like status, in part due to the 2002 Hollywood movie about her life, starring Salma Hayek. In contrast with the modesty of her art, the celebrity-style hype about her life has elevated the artist to iconic status — reminiscent of the Mexican religions icons and retablos (altarpieces) that she collected.

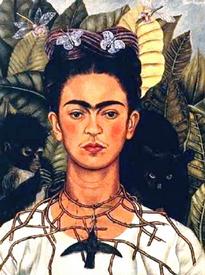

Kahlo is best known for her strikingly distinct image — her face framed by her faint mustache and trademark unibrow, her unconventional marriage to legendary Mexican artist Diego Rivera and her embrace of Communism. Critics claim that her art has largely been overshadowed by the work of her husband and her own mythical status. But as times and artistic sensibilities change, her work is being re-evaluated.

In the largest retrospective of Kahlo’s work to date, Mexico marked the centenary of her birth in grand fashion.

At the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, over 354 pieces went on display July 5, featuring many of her most famous self-portraits, but also lesser-known works, including still lifes, sketches, watercolors and sculpture.

At the Casa Azul (Blue House), Kahlo’s family-home-turned-museum, thousands of artifacts that had been locked away are now on display, providing a broad and intimate glimpse into Kahlo’s life, in an exhibit entitled “Treasures of the Blue House, Frida and Diego.”

The hallmark of both Kahlo’s life and her art was great physical and emotional pain. She suffered from polio as a child and later was injured in a streetcar accident that shattered her pelvis and spine, requiring a three-year convalescence and operations throughout her life. Her physical pain was only eclipsed by the torment of her husband’s many infidelities, including with her sister. Kahlo described her life in terms of two great accidents — the streetcar and Rivera, Rivera being the worse of the two. While his murals depicting the people’s struggle gained huge fame in his lifetime, Kahlo’s deeply personal work was largely overlooked — her first solo showing of her work occurred only a year before her death.

As fans take a closer look at Kahlo’s dreamlike images, unexpected details are revealed, as well as lessons about struggle that are very personal, yet highly relatable. While some critics say that Kahlo outmastered even celebrity-obsessed Pablo Picasso at cultivating her own image, one need not dig too deeply into her work to unearth the great conflicts that marked her life and work.

The duality often seen in her paintings mirrored that of her personal life. She often dressed in men’s clothes and embroidered Tehuana Indian dresses, and responded to her husband’s infidelities with many dalliances of her own — with both men and women. And while her image sometimes was glamorous, she led a fairly domestic life, surrounded by a house full of plants, pets and simple pleasures. Perhaps the genesis of her embrace of her inner paradoxes was the duality of her heritage — born to a Hungarian Jewish father of German descent and a Mexican mother.

Her work screams out the pain of abandonment and loss in an age where little is intimate anymore. Her style is instinctual, at times confrontational, yet surprisingly delicate and accessible. New tenderness is revealed in her portraits of children, particularly in the detailed use of color in a portrait of her baby niece, appearing as a servant girl. Frank sexuality and humor is evident in the still life “The Bride Who Is Frightened to See Life Open,” for which Kahlo posed a bride doll with sliced papayas and watermelons upon a table top.

As new fans have been drawn to Kahlo’s work, the celebrations have spanned the globe.

In Havana, Cuba, Frida is being honored with an exhibit titled “Desde la piel de Eva y con los ojos de Adan” (From Eve’s skin, with Adam’s eyes). In November, her centenary and the 50th anniversary of Rivera’s death will be marked with the program, “Frida y Diego, Voces de la tierra” (Frida and Diego, Voices of the earth).

In Chile, Kahlo’s centenary is being marked with a program entitled “Un abrazo para Frida y Diego” (A hug for Frida and Diego).

In the U.S., the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis has announced a show that will open in October and travel to Philadelphia and San Francisco, featuring 50 Kahlo paintings. The National Museum of Women in Arts in Washington, D.C., is memorializing her with the display of her painting, “Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky,” painted in 1937 for the Russian revolutionary and as a remembrance of their brief affair, along with a small collection of letters and photographs.

Europe and Asia have also joined in tributes to the artist. In Berlin, the anniversary was marked with “The 100 Years,” a photographic exhibit from the 1950s by artist Gisele Freund, and a series of lectures.

In the Philippines, film screenings, book launchings, dance shows and exhibitions celebrated the artist in a program entitled “We love Frida so much.”

In this age of reality shows and staged intimacy, the personal art of Frida Kahlo has arguably eclipsed that of her famous husband, although his heroic stature still resonates today throughout Mexico and the art world. The key to appreciating her art is the understanding that struggle and great progressive change begin first in our own minds and experiences, creating a ripple effect throughout our lives and the lives of others. In that way, we recognize that we all strive for change and engage in the fight — both within ourselves and in our world.

Valency Hastings (vhastings @pww.org) is a graphic designer at the People’s Weekly World.

Comments