WASHINGTON – Sexual discrimination on the job, including sexual harassment, is much more rampant, and takes many more forms, than is generally realized, a new report from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research says.

“A substantial portion of employers each year are subject to a charge,” under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act editorial, the nation’s basic and wide-ranging civil rights law, the 160-page report explains.

“One recent study, covering 1990 to 2002, found that 13 percent of establishments had at least one charge of sex discrimination and 20 percent had at least one charge of racial discrimination. Another found that during a 30-year period, more than a third of employers faced a charge of discrimination.”

The catch is that only one-fourth of those charges ever wind up in court, and even fewer result in court orders against the offending companies and money for the injured workers, the report notes. That’s because the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the main enforcer of the law, first tries to solve the conflicts out of court, through mediation, and most are settled that way.

Nevertheless, the EEOC wound up with 735,293 charges of employment discrimination from 2000-2008: 36 percent on racial discrimination, 30 percent on sex discrimination, 23 percent age discrimination, 20 percent disability discrimination, 11 percent national origin discrimination and three percent religious discrimination. Some cases involved more than one type of bias.

The findings left two panels on the issue discussing the problem and what to do about it – and unions are a key anti-discrimination weapon, said Coalition of Labor Union Women Executive Director Carol Rosenblatt. CLUW co-sponsored the report.

“Unions have anti-sexual harassment policies in place” within many contracts they bargain with firms, Rosenblatt said. “And we have shop stewards to carry them out.” And many unions have “various tools” women can use to combat discrimination.

But sometimes even with the union sticking up for the female workers, its remedies don’t work if the employer is obstinate – refusing to address the problem – or the harasser is in the power position where he can make the decision. That’s when even union women have to turn to the courts or the EEOC, Rosenblatt said.

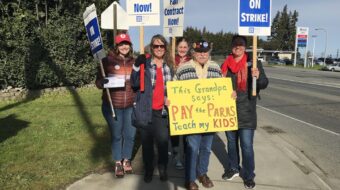

One union, the independent United Electrical Workers, even had to strike when the firm involved retaliated against UE stewards who were fighting sexual harassment.

Unions have other potential remedies for sexual harassment, Rosenblatt added: Firstly, unions should make woman workers aware that the union will fight to stop sexual harassment on the job. That will benefit the women, and the union.

Also – “Make the harasser, not the victim, pay.” Rosenblatt noted that too often the victim leaves her job and the harasser stays in his – and that should change.

The American Federation of Television and Radio Artists uses media its members work in and on – radio, TV, Facebook, Twitter, etc. – to raise consciousness about sexual harassment and discrimination on the job.

The Steelworkers’ Civil Rights department developed a guide for all the union’s locals to deal with sexual harassment issues. It also established a special committee within its department to investigate all sexual harassment complaints it receives from locals when their members are harassed.

Even though the nation’s schools have a female majority among their faculty, schools “are not required to provide anti-sexual harassment training” on the job, Rosenblatt pointed out. But Connie Cordovilla, the American Federation of Teachers’ vice president for civil rights, developed contract language for locals to use when bargaining with school boards. And she’s also told them to warn the boards that “those districts found guilty are viewed more harshly by the courts.”

IBEW also created anti-sexual harassment contract language, Rosenblatt said.

The Transport Workers, who represent the nation’s bus and subway drivers, have taken another tack by developing an anti-sexual harassment course and offering it to employers. The course covers not just sexual harassment within a transportation company, but also teaches female drivers how to deal with harassing passengers.

“A driver faced with a flasher has to know how to respond,” Rosenblatt said.

“But the one constant in all this is that sexual harassment is part of the overall pattern of violence against women. Not all women know about sexual harassment on the job and not all women know where to go when it occurs, so CLUW will continue its education campaign to combat this most ugly form of discrimination,” she pointed out.

In the end, “sexual harassment is about power” and the tools and the stewards can help woman workers battle it, Rosenblatt said.

MOST POPULAR TODAY

Zionist organizations leading campaign to stop ceasefire resolutions in D.C. area

Communist Karol Cariola elected president of Chile’s legislature

Afghanistan’s socialist years: The promising future killed off by U.S. imperialism

High Court essentially bans demonstrations, freedom of assembly in Deep South

Comments