On June 28, 1914, exactly a century ago, a Serbian nationalist, Gavrilo Princip, shot and killed the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and his wife, the Duchess of Hohenberg, in Sarejevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina. It triggered the outbreak of World War I – one of the deadliest conflicts in history – just one month later.

Franz Ferdinand was a disagreeable man, abusive to the peasants on his estate in Bohemia. He had a chip on his shoulder because the emperor’s court snubbed his wife for not being of royal birth. Ironically, Franz Ferdinand was one of the few people in the Austro-Hungarian ruling class who did not want war and was working to prevent it. This made him enemies in the ruling class and the army, who were spoiling for a fight with neighboring Serbia. But it did not make him any friends in Serbia. Serbia’s leaders were afraid that Franz Ferdinand’s idea of conciliating the Slavs in the empire by giving them a federated state (alongside Austria and Hungary) would ruin the plan to break off south-Slavic areas and create a united kingdom of southern Slavs.

So when Austrian security in Sarajevo, where the archduke had gone to inspect troops, practically delivered him to the waiting assassins, there were few tears, and the Austro-Hungarian leadership eagerly jumped at the opportunity to crush the Serbs forever. After making sure that Germany would back them, they presented the Serbian government with an ultimatum deliberately designed to be rejected. The rest is history.

The killing of the archduke and his wife, however, was not the “cause” of the First World War. In the years leading up to Sarajevo, tensions were building to such a degree that everybody could see that some small incident could set off a huge conflagration. To imperialist rivalries over colonies, trade and markets were added ideological factors including extreme nationalism and militarism. Furthermore, not only the Austro-Hungarian Empire but also the Russian and Ottoman ones were suffering such extreme stresses that their demise was regularly predicted, and their leaders were capable of doing anything to save their thrones.

This is why the socialist parties of Europe and beyond put the issue of preventing war as one of the major points on the agenda of the 7th Congress of the Second International, which took place in Stuttgart, Germany, in August 1907. This event, attended by 886 delegates from almost all major countries of Europe plus the United States and India, brought together the most outstanding leaders of the socialist movement at that time, including V. I. Lenin, Max Litvinov and Anatoly Lunacharsky from Russia, Rosa Luxemburg, August Bebel, Eduard Bernstein, Karl Kautsky, Franz Mehring, Karl Liebknecht and Clara Zetkin from Germany, Jules Guesde, Jean Jaures, and Eduard Hervé from France, and Daniel DeLeon and Morris Hillquit from the United States. Both sides of the growing left-right split in world socialism were amply represented.

In his brief report on the conference, Lenin’s sketches on matters of women’s suffrage, colonialism, immigration and the relationship between political work and labor unions show clearly how much progressive humanity and the working class today owes to the left-wing socialists, and not to the so-called moderates. Lenin, Luxemburg, Zetkin and other “lefts” took clear stands against colonialism, for complete voting rights for all women, and for rights of all immigrant workers.

The leftist delegates prevailed in passing a resolution that denounced militarism as “the chief weapon of class oppression,” called for anti-militarist campaigns among the youth, and insisted that socialists unite not only to oppose war, but also to use a war crisis to advance socialist revolution.

However, when war actually broke out in August 1914, the apparent anti-war stance of the socialist movement fell to pieces. Major sectors of the socialist movement forgot the Stuttgart resolution and lined up behind the war aims of their ruling classes and governments. Several very prominent socialist leaders stayed firm, including Debs in the United States (who later did hard jail time for speaking out against U.S. involvement in the war), Jaures in France (who was assassinated by a right-wing nationalist for opposing the war) and James Keir Hardie in Britain (whose death was supposedly hastened because he could not stop the war). Only Debs was able to carry his party with him. Yet this did not stop the U.S. from plunging into the war in 1917.

Irredeemably split on the war issue, the leadership of the Second International ceased to function. A year into the war, the left wing of the socialist movement organized another conference, in Zimmerwald, Switzerland, but by that time it was evident that the left-right breach in the socialist movement could not be healed. In Stuttgart, the socialists tried to unify to put an end to war, but the war put an end to socialist unity instead. The “Zimmerwald left” became the nucleus of the future world communist movement.

Why did Sarajevo negate the high hopes of Stuttgart? First of all, because the commitment to working class unity was not strong enough to override national prejudices. Once the war started, in most countries those who spoke out against it faced prison, and the opposition was weakened by enhanced repression.

The lesson for us today is that we must spare no effort to build international working class unity against war, militarism and imperialism, starting with a firm opposition to war plans of our own ruling class.

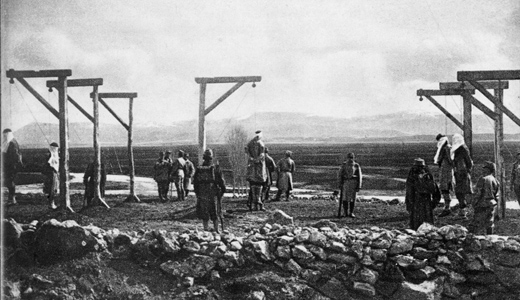

Photo: Austro-Hungarian troops killing Serbian civilians in Herzegovina in the aftermath of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, 1914. Wikimedia (CC)

Comments