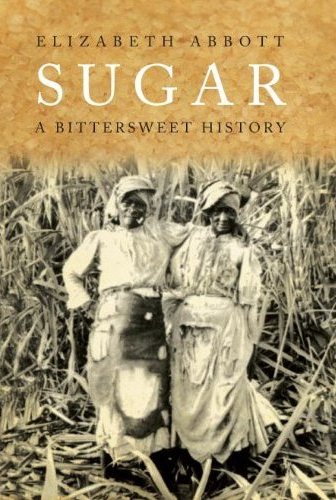

Book review

“Sugar A Bittersweet History”

By Elizabeth Abbott

Penguin Group, 2008, 453 pp

I liked the book “Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World.” There was something fascinating to me in learning about world history and development through the many threads that led to and stemmed from one specific fish.

That’s why “”Sugar A Bittersweet History” by Elizabeth Abbott caught my eye on the “new nonfiction” library shelf recently. And I wasn’t disappointed. The history of sugar, as researched and told by Abbott, is a fascinating, complicated and ongoing journey that takes us through the brutal depths of slavery and racialized society to the heights of resistance and abolition, to the ingenuity of invention from Hershey’s milk chocolate to Brazil’s biofuels.

Abbott, a Canadian with roots in Antigua, is a research associate at Trinity College, University of Toronto, where from 1991 to 2004 she was dean of women. She has also written other books, including “A History of Marriage” and “A History of Celibacy.”

The book is divided into four parts. Abbott devotes much of the history to the complexities and brutalities of slavery, the African slave trade and the effects of a racialized society. The book’s primary focus is on Britain and its Caribbean island colonies, plus Haiti and Cuba.

In her treatment of this topic, she delves into not only the brutality of the sugar plantation system with its forced labor and control of human beings, of which there are most vivid examples, but also other aspects like the role of slave women, family structures, resistance and revolution, and the various interests behind the abolitionist movement in the Caribbean and United Kingdom.

Also woven into sugar’s story are the introduction of sugar to Europe from its South Pacific and Asian origins; sugar and the development of Western diet; cane sugar’s rivals: sugar beet and now corn; indentured labor of Indian, Chinese and other peoples; and the impact of sugar today on the environment, public health and otherwise.

I found the history of the movement to abolish slavery and the African slave trade most interesting. Abbott says the movement, like a “hybrid spider propelled by unmatched legs” formed a coalition of mutual anti-slavery interests.

She writes, “Each leg was formed by members of the following groups: men and women of the [British] working class; black residents in England; West Indian slaves, free blacks and coloreds; renegade West Indian missionaries; Quaker and religiously motivated non Quaker men; Quaker and religiously motivated non Quaker women; politically minded reformers; and anti-protectionist free traders and East Indian sugar interests. From time to time over the more than half century of anti-slavery effort, a leg would shrivel away or be cut down and then regenerate.”

This is the movement that propelled such figures as British parliamentarian William Wilberforce into prominence.

Abbott makes a point of separating the men’s and women’s movements because they had separate organizations, tactics and focuses. In the 1790s, the world’s first use of a boycott as an economic weapon for social justice was launched, and it was the first time such a campaign “enlisted women as participants” by acknowledging women’s power in buying, using and serving sugar.

Years later, after the abolition of the slave trade, but not slavery, women abolitionists revived the sugar boycott, and pushed for immediate emancipation as opposed to gradualism that many men, like Wilberforce, preferred.

I was happy to see that Abbott borrows from the Marxist tradition, quoting extensively from Eric Williams’ “Capitalism and Slavery” and “From Columbus to Castro.” Williams, a political and intellectual giant from the Caribbean, was the first prime minister of Trinidad and Tobago. Another well-known Marxist source she uses is E.P. Thompson’s “The Making of the English Working Class.”

And for those who enjoy trivia and pop culture as well as the big picture, Abbott doesn’t disappoint, with lots of fun facts throughout the book. For example, she informs us that the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis introduced “fast food” into the American diet; and the word “tips” comes from the early British tea gardens, where locked wooden boxes with a slit in which to place money sat on tables with the sign, “To Insure Prompt Service” (TIPS).

As to the United States, Abbott outlines sugar’s role in U.S.-Cuba relations, Louisiana’s industrial agricultural development, California’s multi-racial labor organizing, upper Midwest sugar beet farms, overthrow of the sovereign state of Hawaii, and creation of Hershey, Pa.

Parts of the book were so engrossing, I could fly right through it. Other parts were either so dense or uninspired that it took me longer. All in all, I had to renew the book four times before I finished it. But it was well worth the overdue charges and library trips.