GLENDALE, Calif.—The Antaeus Theatre Company’s Southern California premiere production of Nambi E. Kelley’s theatrical adaptation of Richard Wright’s 1940 novel Native Son (seen opening night, April 19) reveals how this work becomes more powerful, more relevant and more disturbing with each passing year.

Two previous theatrical adaptations, as well as two films (one of them with the novelist himself playing the lead role of Bigger Thomas), have been made from this iconic work. Kelley’s 90-minute whirlwind premiered in 2014 in Chicago, the setting of Wright’s novel. It is a stupendous coup de théâtre.

Book, play, film: In any form this story is a coruscating indictment of racism and poverty in America, themes that rush like a polluted river through our history, across the headlines of our newspapers and our media monitors. They are made to seem indelible and ineradicable, except we know they are not: Other countries have overcome such historical scourges that tarnished their history, and if it ever gathers the will, the U.S. can do it too.

One step people here in Southern California can take is to run, run, run and get tickets to this riveting piece of stagework.

Many readers will already be familiar with this story. The Wikipedia refresher might be helpful. For purposes of concision and theatrical punch, Kelley’s version draws a tight focus down on the Bigger Thomas character, who appears in virtually every scene, as he struggles with his memories, his doubt, his questions, and his slowly evolving consciousness. Only 20 when we meet him, he is the scared and scarred bully of his neighborhood, a product of the penurious slums, of fatherlessness, of the subservience that is expected from him by white society in Chicago no less than in the Deep South, and his all-consuming but understandable rage at the world.

If the good Christians in his family believe they can “Steal away, steal away to Jesus” as the familiar spiritual/escape fantasy has it, Bigger sees the airplanes flying overhead and imagines he could be a pilot one day and go wherever he likes.

W.E.B. Du Bois, as early as 1897, identified the crushing sense of “double consciousness” that all Black people in America have to live with, a concept he incorporated into his 1903 book The Souls of Black Folk. He described it as the “sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness, an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder…. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of opportunity closed roughly in his face.”

In Kelley’s adaptation, this mirroring effect between the “two souls” is achieved by Bigger (John Chaffin), dressed in humble work clothes, always being shadowed by “The Black Rat” (Noel Arthur), Bigger’s better angel, conscience and alter ego, wearing a crisp fedora, neat tie and vest, an idealized version of the Black man as urbane Chicago boulevardier.

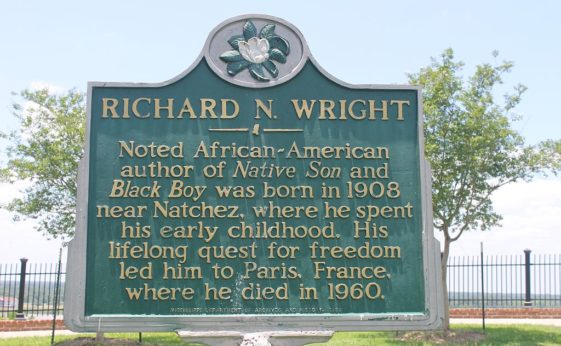

A native of rural Mississippi, Richard Wright (1908-1960) started writing stories as a teenager. When he migrated north to Chicago in 1927, he joined the Communist Party’s John Reed Club to develop his writing skills, and in short order joined the party. In 1937 he moved to New York to write for the Daily Worker, predecessor of the People’s World. His first book, published in 1938, was Uncle Tom’s Children; and with Native Son he became famous. Wright remained in the Communist Party until 1944, and later in life was drawn to the Pan-African movement.

Wright was obviously influenced by writers such as Emile Zola, Victor Hugo and Theodore Dreiser, whose sense of hyperrealism in the naturalist school with which they are identified predicated that human behavior results from a person’s surroundings and influences. Mix that with the socialist realism of Wright’s own Communist environment, and we get characters whose actions can almost be predicted just from studying the place and class they come from.

That does not mean that Wright draws caricatures or shallow people. Some of the most intriguing characters, as we meet them in Kelley’s play, are the “liberals” who support the NAACP, hire Black people, even a reform school graduate such as Bigger, and profess somewhat progressive ideas, while at the same time owning rat-infested slum housing and determining where in Chicago certain kinds of people should and shouldn’t be living. The classy Mrs. Dalton (Gigi Bermingham), the blind mother of Mary (Ellis Greer) whom Bigger inadvertently kills, is such a person.

Mary has traveled somewhat further left in her thinking, involved romantically as she is with Jan Erlone (Matthew Grondin), a Communist Party recruiter who tries to befriend and educate Bigger, finding him in the end too damaged a person to be moved by Marxist ideas. The novel expands on the role of the CP in supplying a Jewish defense attorney for Bigger, Boris Max, but this role has been excised from Kelley’s distilled treatment. She does, however, include the party’s leading role in defending the nine Scottsboro youths falsely accused in 1931 of raping two white women on a train, and saving them from death sentences, if not prison. The play shows how racism and anti-Communism were consistently paired to drive a wedge between American people and distract them from the larger issues of class privilege.

The program contains useful essays on Native Son, one of them by dramaturg Dylan Southard on the “Character of Chicago” in the play, bringing out facts about the Great Migration northward after World War I that carried some six million African Americans toward jobs and futures denied to them in the rural South, among them the Thomas family.

Director Andi Chapman’s note ties the Native Son story to the larger narrative that screams out at us every day:

“Skittles, I can’t breathe, Philando, Brown, had my cell phone in grandma’s backyard, Oh no, not Bland, and the list goes on and on and on—. My prayer Lord is that it would STOP—this—identification of this man, this black man, this woMan as something other than huMan—. I pray Lord it must STOP.

“No one’s life is perfect. An accident, sometimes small, sometimes in great magnitude, can change the very trajectory of one’s life. Sometimes those mistakes are made because one believes that they entered this world dead on arrival, and every day that belief is tragically reinforced. This belief invites more tragedy until there is no catching this train.”

In her direction, every gunshot is a new Black man murdered. Some in the angry white mob calling for Bigger Thomas’s death carry tiki torches (read: Charlottesville). Every newspaper peddles racist scandal and fear. Every police raid spells intimidation and violence if you’re not obsequious enough to your armed masters.

The artistic directors cite the enduring relevance of staging this play now, more than 75 years after Wright’s novel first appeared: “The crushing vise of institutional racism, economic barriers and the continued lack of opportunities for people of color continue to create modern-day Bigger Thomases throughout our nation.”

Edward E. Haynes, Jr.’s scenic design for the “labyrinth of Chicago’s black belt and surrounding areas as it appears in Bigger’s mind” is a large wooden construction, seemingly made of charred timbers as if after a raging fire. It captures the depressing substandardness of the Windy City while also providing smaller spaces representing the Thomas and the Dalton homes, a neighborhood grocery store, a movie theatre that screens the fashions and figures of stylish white women, and the cold, snowbound streets. Everywhere the pall of race awareness colors the air: This place you can go, that place you can’t, this apartment can be taken from you, that elegant home you may enter humbly only by the gracious leave of the seigneur. Grainy video depicts a Chicago of brick factories and rolling trains.

At a reception following the opening, the producers stated that they had been awaiting the right moment to stage this play, which involved the opening of the new space for Antaeus in Glendale, and the availability of this particularly strong cast. Aside from those named above, other actors in the superb nine-person cast include Victoria Platt as Hannah Thomas, the deeply religious matron of the family; Brandon Rachel as Bigger’s younger brother Buddy; Mildred Marie Langford as sister Vera and as the alcohol-dependent girlfriend Bessie; and the menacing Ned Mochel as the private investigator Britten who pursues Bigger with a passion like that of the obsessive Inspector Javert in Les Misérables.

In a word, theatre doesn’t get any better than this. It’s a requiem for an America that’s still very much alive.

Native Son plays through June 3 on Fri. and Sat. at 8 pm, Sun. at 2 pm, Thurs., May 31 at 8 pm only; and Mon. at 8 pm, April 30, May 7, 14 and 21 only. The Kiki & David Gindler Performing Arts Center is located at 110 East Broadway in downtown Glendale. For tickets and other information call (818) 506-1983 or visit the company website.