The news likely received little attention at the time, coming as it did the day after the assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., but 50 years ago, on April 5, 1968, the Saugus Iron Works was added to the National Park Service system and renamed the Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site.

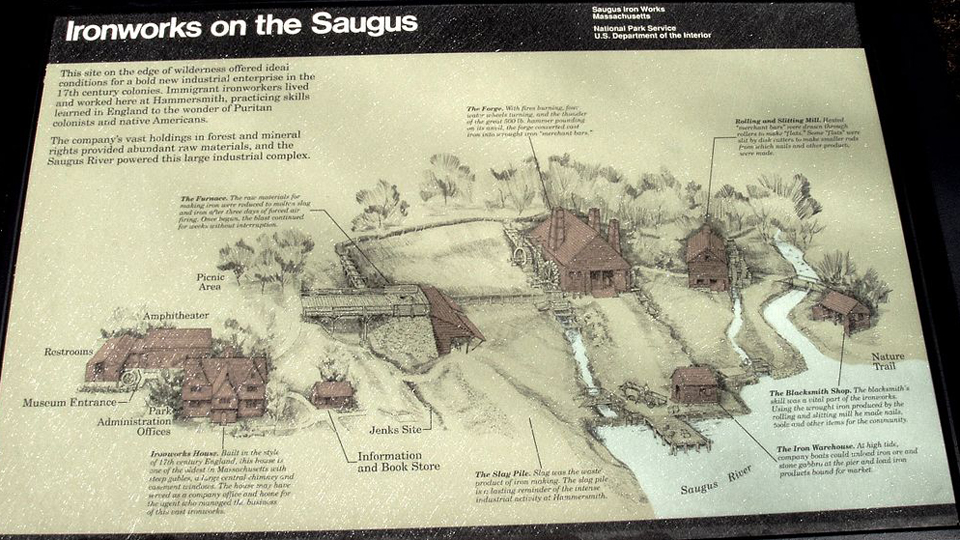

Saugus Iron Works is about 10 miles northeast of Boston in Saugus, Mass. It’s where the first integrated ironworks in what would become the United States was founded by John Winthrop the Younger. It was in operation between 1646 and approximately 1670. The site includes the reconstructed blast furnace, forge, rolling mill, shear, slitter, and a quarter-ton drop hammer.

The facility is powered by seven large waterwheels, some of which are rigged to work in tandem with huge wooden gears connecting them. It has a wharf to load the iron onto ocean-going vessels, as well as a large, restored 17th-century house.

During the 17th century, iron was used to manufacture a number of indispensable goods, including nails, horseshoes, cookware, tools, and weapons. The production of iron required a complex manufacturing process that could only be done by an industrial enterprise. This process was not available in North America during the early years of English colonization, which meant that all iron goods had to be imported. As it took at least two months to sail to the nearest foundry, iron goods were very expensive.

Winthrop believed that because the colonies had a cheap and abundant supply of raw materials, an iron works in Massachusetts could produce goods that could be sold profitably in the New England and Chesapeake Colonies as well as in England itself. In 1641, Winthrop sailed to England to get the capital he needed. The Company of Undertakers for the Iron Workes [sic] in New England was founded to finance the project. Winthrop originally selected a site in Braintree, Mass., and construction was completed in 1645. But the site proved unsuccessful due to a lack of iron ore in the area and an inadequate supply of water.

In 1645, the Undertakers informed Winthrop that Richard Leader, a merchant from East Sussex, England, who knew the ironmaking process, would replace him as manager. Leader chose another location in Lynn, Mass. (part of present-day Saugus) on the Saugus River. The river was navigable for shallow draft vessels and could be dammed to power machinery. The surrounding forests could be used to make charcoal. Bog ore could be mined from nearby ponds, swamps, and riverbeds. Limestone, which was normally used for flux, a chemical cleaning agent, was not available, but it was found that gabbro, which could be mined nearby, would work as a flux.

The new iron works, called Hammersmith, began operations in 1646. It consisted of a blast furnace for producing pig iron and gray iron (the latter was poured into molds to make firebacks, pots, pans, kettles, and skillets), a forge where pig iron was refined into wrought iron, a 500-pound hammer used to make merchant bars, which were sold to blacksmiths for manufacture into finished products, and a rolling and slitting mill where flat stock that could be used to manufacture nails, bolts, horse shoes, wagon tires, axes, saw blades, and other implements was produced. At the time, it was one of the most technologically advanced iron works in the world. Once functioning, the iron works ran for thirty weeks of the year and produced one ton of cast iron a day.

Skilled ironworkers were brought over from England. Many of them did not fit in with the local Puritan society. They often ran afoul of its laws, getting arrested for crimes such as drunkenness, adultery, gambling, fighting, cursing, not attending church—and wearing fine clothes. The less experienced local men who worked there suffered frequent and sometimes fatal accidents. Another source of labor was indentured servants, who typically worked at Hammersmith for three to seven years for little or no pay in exchange for their passage to Massachusetts and the provision of food, clothing, housing, and other necessities.

In 1650, Leader left the iron works to go into the sawmill business. John Gifford and William Aubrey assumed management, Gifford serving as ironmaster and Aubrey doing the accounting.

Although the factory produced a respectable quantity of iron, due to labor costs, financial mismanagement (and possibly embezzlement), and a number of lawsuits, it seldom operated at a profit. It closed around 1670.

Reconstruction and restoration

After the iron works closed, the site fell into disuse and became hidden by underbrush. In 1898, the Lynn Historical Society erected a historical marker near the site which read:

“The First Iron Works. The first successful iron works in this country established here. Foundry erected in 1643. Joseph Jenckes built a forge here in 1647 and in 1652 made the dies for the first silver money coined in New England. In 1654 he made the first fire engine in America.”

Eventually, the plaque too became obscured by the underbrush and remained camouflaged until it was discovered during the restoration project.

In 1915, antiquarian Wallace Nutting purchased the Appleton-Taylor-Mansfield House, a 1680s farmhouse near the iron works site which was believed to be the former home of the ironmaster. He renamed the home Broadhearth and undertook an extensive, albeit embellished, restoration of the home. Nutting used it to showcase his collection of antiques, photographs, and reproduction furniture. In 1917 he added a blacksmith’s shop to the property and hired a blacksmith to manufacture and sell reproductions of early ironwork.

Running into financial troubles, Nutting sold the house and it changed hands several times. The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) purchased a piece of the property. Eventually, William Sumner Appleton, president of the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, created a nonprofit, called the First Iron Works Association (FIWA), to purchase and maintain the property. In 1943 FIWA purchased the farmhouse as well as the DAR’s piece of the property.

Quincy Bent, a retired executive of Bethlehem Steel residing in Gloucester, Mass., was interested in the property’s slag pile, which indicated that the site could contain the remains of an iron works. Bent eventually convinced the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI) to fund the restoration of the iron works.

In 1948, FIWA approached archaeologist Roland W. Robbins, who had discovered the site of Henry David Thoreau‘s cabin on Walden Pond, about trying to find the site of the iron works. Robbins was intrigued by the idea of digging at an over 300-year-old site where there was little information, and no plans or sketches, yet may have been the first iron-manufacturing plant in the American colonies. His excavations uncovered the major manufacturing units of the factory, including the foundations of buildings, remains of the blast furnace, holding ponds and canal, the 500-pound hammer used in the forge, and a waterwheel that powered the bellows for the blast furnace, along with its wheel pit. The wheel was saved by biologists from Harvard University, who developed a process to preserve it.

In total, more than 5000 artifacts were found, but in 1953 Robbins left the project, believing that FIWA was more committed to base the reconstruction of the iron works primarily on documentary evidence instead of archaeological evidence.

The Boston architecture firm of Perry, Shaw & Hepburn, Kehoe & Dean, which was responsible for the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg, was hired to reconstruct the iron works. The reconstruction was based on archeological evidence and historical documents, as well as partially on conjecture.

The Saugus Iron Works was opened on September 18, 1954, the first day of Saugus’ three-day 325th anniversary celebration. Benjamin Franklin Fairless, chairman of U.S. Steel, served as master of ceremonies at the dedication. Also participating were Sen. Leverett Saltonstall, Gov. Christian Herter, FIWA President J. Sanger Attwill, and Inland Steel Company Chairman Edward L. Ryerson.

Becoming a National Park

After it opened to the public, Saugus Iron Works operated as a private museum run by FIWA and funded by AISI. In 1961, the AISI announced that it would no longer pay its annual maintenance subsidy, which left the future of the site uncertain. That is when the National Park Service became involved. The park is open seasonally, spring through fall, surely a destination for travelers interested in labor and social history. Free ranger-guided tours are offered May 1-October 31. The official National Park Service website for the Saugus Iron Works can be found here.

Sources: National Park Service and Wikipedia.

Comments