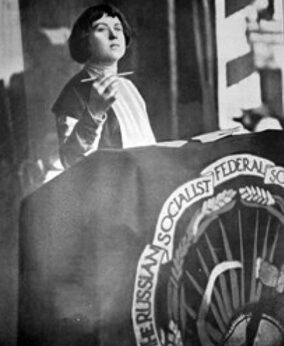

Born 150 years ago, Alexandra Kollontai was an outstanding figure in the Russian communist movement. As People’s Commissar for Social Affairs in Soviet Russia, Kollontai was the first woman in history to serve in a government cabinet.

Alexandra Kollontai, born 150 years ago on March 31, 1872, was an outstanding figure in the Russian communist movement. In exile, she was internationally active as a speaker and author. In Germany, she became friendly with Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, and Clara Zetkin. As People’s Commissar for Social Affairs, Kollontai was the first woman in history to serve in a government cabinet. From 1922, she was the USSR’s first ambassador to Norway and Sweden.

Kollontai came from a wealthy St. Petersburg family. Her father was descended from Ukrainian landowners and later became a general in the Imperial Russian Army. Her mother was the daughter of a Finnish timber merchant and a Russian noblewoman. As a child, Alexandra (Shura) spent many summers on the family estate in Finland. She was fluent in Russian, Finnish, English, German, and French, language skills that not only benefited the revolutionary movement but later also the Soviet diplomatic service. Within the Russian communist movement, she fought for women’s rights and was also instrumental in the social legislation of the early Soviet republic.

Kollontai’s active political work began when she gave workers evening classes in St. Petersburg in 1894. Through this, she became part of the Political Red Cross, an organization supporting political prisoners, which worked partly underground. August Bebel’s Woman and Socialism left a deep impression in 1895 and influenced her future thinking and work.

In 1896, Kollontai experienced her first direct encounter with capitalist industry in a large St. Petersburg textile factory. Shortly afterwards, she participated in leafleting and fundraising campaigns in support of a mass strike in the textile industry. The 1896 strikes consolidated her certainty of the need for proletarian revolution. In 1899, she joined the illegally operating Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP).

In 1905, she began to turn actively to the women’s question. Her work The Social Basis of the Woman Question was the first major exposition by a Russian Marxist on the subject. In it, she not only advocated the overthrow of the capitalist system, but she also explained the need to restructure the family itself in order to achieve true emancipation.

Between 1905 and 1908, Kollontai organized women workers in Russia to fight for their own interests against capitalists, against bourgeois feminism, and against conservatism and patriarchy in the socialist organizations. She thus laid the foundation for a mass movement.

Like many Russian socialists, Kollontai remained neutral during the split between Bolsheviks and Mensheviks in 1903. In 1904, she joined the Bolshevik faction and gave courses on Marxism for them. In 1905, she joined Trotsky, leaving the Bolsheviks in 1906 over the question of boycotting the elections to the undemocratically-elected Duma, where she believed it was nevertheless possible to stand up for left-wing demands and expose the government’s machinations.

Between 1900 and 1920, Kollontai was considered the RSDLP’s leading expert on the “Finnish question.” She wrote two books, numerous articles, and was an adviser to RSDLP members in the Tsarist Duma as well as a liaison with Finnish revolutionaries. In 1908, when she advocated Finland’s right to armed insurrection against the Tsarist Empire, she was forced into exile.

From the end of 1908 until 1917, Kollontai lived in exile. In the period before the First World War, she traveled to the U.S., Britain, Denmark, Sweden, Belgium, and Switzerland. Her autobiographical sketch Autobiography of a Sexually Emancipated Communist Woman reads:

“I lived in Europe and America until the overthrow of Czarism in 1917. As soon as I arrived in Germany, after my flight, I joined the German Social Democratic Party in which I had many personal friends, among whom I especially numbered Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Kautsky. Clara Zetkin also had a great influence on my activity in defining the principles of the women-workers movement in Russia. Already in 1907, I had taken part, as a delegate from Russia, in the first International Conference of Socialist Women that was held in Stuttgart. This gathering was presided over by Clara Zetkin and it made an enormous contribution to the development of the women-workers movement along Marxist lines.”

Long before the war, Kollontai began to agitate tirelessly against the threat of war. At a speech in Stockholm on May 1, 1912, she declared:

“The capitalists always say: ‘We must arm ourselves because we are threatened by war!’ And they point to their sacred symbols: militarism on land, militarism on the high seas, and militarism in the air. They summon the specter of war in order to put it between themselves and the red specter. They call for war in order to free themselves from the specter of social revolution.

“But the International answers them with one united call: ‘Down with war!’ The workers know that behind the threat of war there stands the capitalist state that wants to burden the people with new taxes, there stands the war industry that wants to increase its profits.”

She also became involved in the anti-war movement in Germany and Austria. She was in the Reichstag when the war credits were voted for in August 1914:

“Only Karl Liebknecht, his wife Sofie Liebknecht, and a few other German Party comrades, like myself, espoused the same standpoint and, like myself, considered it a socialist’s duty to struggle against the war. Strange to say, I was present in the Reichstag on August 4, the day the war budget was being voted on. The collapse of the German Socialist Party struck me as a calamity without parallel. I felt utterly alone and found comfort only in the company of the Liebknechts. With the help of some German Party friends I was able to leave Germany with my son in August of 1914 and emigrate to the Scandinavian peninsula.”

In Sweden, she was imprisoned for anti-war propaganda. After her release, in February 1915, she went to Norway where, together with Alexander Schlapnikov, she served as a link between Switzerland, where Lenin and the Central Committee were staying, and Russia. In June 1915, she broke with the Mensheviks and officially rejoined the Bolsheviks. In September 1915, she was centrally involved in the organization of the Zimmerwald Peace Conference. Her paper Who Needs the War? (1915) was translated into several languages and circulated in countless editions and millions of copies. She made two lecture tours of the USA, attended a memorial service for Joe Hill in Seattle, and spoke from the same platform as Eugene Debs in Chicago.

With the outbreak of the February Revolution in 1917, Kollontai returned to Russia and advocated a clear policy of non-support for the provisional government. She was elected a member of the Central Committee of the Petrograd Soviet. Kollontai continued to agitate for revolution in Russia and began her involvement with the Bolshevik women’s newspaper Rabotnitsa (Работница, Woman Worker), urging the Bolsheviks and the trade unions to pay more attention to the organization of women workers. In May 1917, she took part in the strike of women laundry workers demanding the communalization of all laundries. The industrial action lasted six weeks, but the Kerensky regime failed to meet the workers’ demands.

After the revolution, Kollontai was elected Commissar for Social Affairs in the new Soviet government. Kollontai’s description in the Autobiography gives a vivid impression of her work in the complete transformation of the first revolutionary period:

“My main work as People’s Commissar consisted in the following: by decree to improve the situation of the war-disabled, to abolish religious instruction in the schools for young girls which were under the Ministry (…), and to transfer priests to the civil service, to introduce the right of self-administration for pupils in the schools for girls, to reorganize the former orphanages into government Children’s Homes (…), to set up the first hostels for the needy and street-urchins, to convene a committee, composed only of doctors, which was to be commissioned to elaborate the free public health system for the whole country.

“In my opinion, the most important accomplishment of the People’s Commissariat, however, was the legal foundation of a Central Office for Maternity and Infant Welfare. The draft of the bill relating to this Central Office was signed by me in January of 1918. A second decree followed in which I changed all maternity hospitals into free Homes for Maternity and Infant Care, in order thereby to set the groundwork for a comprehensive government system of prenatal care. (…)

“A special fury gripped the religious followers of the old regime when, on my own authority (the cabinet later criticized me for this action), I transformed the famous Alexander Nevsky monastery into a home for war invalids. The monks resisted and a shooting fray ensued. The press again raised a loud hue and cry against me. The Church organized street demonstrations against my action and also pronounced ‘anathema’ against me…”

In 1918, Kollontai opposed the ratification of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and resigned from the government so as not to jeopardize the unity of the Commissariat by her opposition on such a crucial question. The treaty meant the loss of large European territories, including Finland and Ukraine, for Soviet Russia. With this position, she opposed Lenin, for whom peace was a priority.

She remained active as an agitator and organizer, however, and played a key role in organizing the First All-Russian Congress of Women Workers and Peasants, serving in leading posts and founding the Women’s Committee (Zhendotel/Женотдел) of the Communist Party in 1919 together with Inessa Armand and Nadezhda Krupskaya. This body directed its work towards improving the living conditions of women throughout the Soviet Union, combating illiteracy, and educating women about the new marriage, education, and labor laws. In Soviet Central Asia, the Zhenotdel sought to improve the lives of Muslim women through literacy, education, and ‘unveiling’ campaigns.

The Zhenotdel also introduced abortion legalization for the first time in history, in November 1920. In one of several writings on the status of women, Kollontai wrote in 1919 in Sexual Relations and the Class Struggle about her vision of a truly free society in which equality is not solely legislated, but is only achieved:

“when their psyche has a sufficient store of ‘feelings of consideration,’ when their ability to love is greater, when the idea of freedom in personal relationships becomes fact and when the principle of ‘comradeship’ triumphs over the traditional idea of inequality and submission. The sexual problems cannot be solved without this radical re-education of our psyche.”

In 1921, she came into conflict with the Communist Party and Lenin directly when she publicly declared her support for the Workers’ Opposition, a grouping against party centralism. The grouping was dissolved and Kollontai remained in critical opposition within the party.

In 1922, at her own request, she entered the Soviet diplomatic service first in Norway, then in Mexico, then again in Norway and Sweden. She comments:

“Naturally this appointment created a great sensation since, after all, it was the first time in history that a woman was officially active as an ‘ambassador.’ (…) Nevertheless, I set myself the task of effecting the de jure recognition of Soviet Russia and of re-establishing normal trade relations between the two countries which had been broken by the war and the revolution. (…) On February 15, 1924, Norway in fact recognized the USSR de jure.”

Alexandra Kollontai also acted as a negotiator of the 1940 Finnish-Soviet peace treaty and served the USSR with great sensitivity. Until her retirement in 1945 on health grounds, Kollontai lived abroad as a diplomat. Thereafter, and until her death on March 9, 1952, she served the Soviet Foreign Ministry as an advisor.

Comments