It’s that time of year again. Public companies have sent out their financial statements ahead of their spring annual general meetings. Reporters are reading them, gasping at the continued enormity of CEO pay—as they have been doing for 40 years—then reporting them in tones of outrage.

Equilar reported that CEO pay in 2021 increased 20% from 2020 while median worker pay decreased 8%.

Ohio’s just-defeated Democratic Congressional primary candidate Nina Turner summarized the situation well in a tweet this past April 22:

Elon Musk 2012: $2 billion, 2022: $266 billion

Jeff Bezos 2012: $18 billion, 2022: $180 billion

Federal Minimum Wage 2012: $7.25, 2022: $7.25

But this fury against CEO pay excessiveness has been going on since the 1980s. At that time, shareholder activists formed “say on pay” groups, demanding that they get to vote on executive compensation. After decades of trying, they couldn’t even get CEO pay as an item on the agenda for corporations’ annual general meetings.

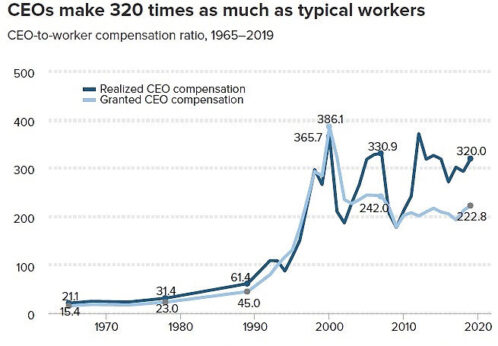

By 1990, voter indignation at the rising CEO-to-worker pay gap swelled to the point that Bill Clinton made it a major promise of his “Putting People First” campaign that if he was elected, he would put an end to it. Clinton got elected in 1993 and immediately said he would keep his promise. Let’s look at a graph prepared by the Economic Policy Institute that shows the rise in CEO to worker-pay ratio from the mid-1960s to 2018. Notice how after Clinton’s reform, the ratio skyrocketed.

Here’s why: Clinton proposed that CEO pay be capped at $1 million for tax deductibility by the corporation. Anything over that could not be deducted as an expense. Then, according to Robert Reich in his documentary Saving Capitalism, Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin, a former CEO himself—of Goldman Sachs, no less—convinced Clinton to make an exception for compensation that was related to performance. The Board of Directors could award additional compensation but only in the form of stock or stock options in the corporation, based on the Board’s view that the CEO’s performance merited it.

The big bump you see for compensation in the graph in 1993 is mostly in stock and stock options.

Although Clinton stayed in power until 2001, no thought was given to correct a policy that was obviously doing the opposite of what he had promised. Nothing was done in the next two G.W. Bush terms either, of course. When Obama took office in 2009, he faced a similar voter cry of outrage. Bankers who had screwed up so badly that they had put the entire financial system in jeopardy were taking huge bonuses for their incompetence during that time, that was bad enough in itself—but out of the bailout money!

Obama, calling this conduct “shameful,” vowed to take “the air out of golden parachutes” and put a cap on their bonuses at $500,000 until the bailout was repaid—unless, yes, you guessed it, they were related to performance and taken in stocks or stock options.

It’s hard to restrain making a seriously sarcastic comment, but given the evidence over some 16 years of the complete failure of the Clinton solution, why did Obama adopt it? And I suppose, a better question is, why did the American voters not understand that this solution was no solution? Could it be that there are important ways that the corporate system works that are kept from the education system so that the voters don’t have the scaffolding to understand what is happening when it comes to corporate reform that affects the upward transfer of wealth?

Then in 2010, the Democrats declared another solution by including a provision in the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill answering the say-on-pay movements to finally require that corporations place the item of CEO compensation on the agenda of the annual general meeting—albeit for a voluntary vote.

So let’s look again at the graph above. Another reform that did nothing over 10 years! And why?

Bust the myth of shareholder control

The structure of a public corporation appears to be based on a democratic model. Shareholders elect the Board of Directors, and the Board of Directors has the power to hire and fire the CEO. The CEO runs the company and has the power to hire and fire everybody else.

If the shareholders think that the Board of Directors is setting the CEO pay too high, they could simply vote for members who will do what the shareholders want. But that can’t be true because shareholders have been trying to get some restraint put on CEO pay since the 1980s. So what is the real situation, and why is it never explained?

In practice, the theoretical model is completely subverted. The CEOs actually (s)elect the Board of Directors; so if the members want to keep their lucrative directors’ fees, they do the CEO’s bidding. Here’s how the CEOs do it.

When the corporation sends out the notice of the annual general meeting, it includes a proxy form. This form allows the shareholder to nominate someone else to vote on behalf of their shares. A lot of shareholders have diverse portfolios that may include a manufacturing company, a tech company, a medical devices company, and so on. They have no idea of how to run any particular company or who the candidates are for the Board of Directors, and they aren’t going to travel to the head office for the meeting.

They are only interested in getting the best dividends and capital gain on the value of the shares. They do one of two things: They sign the proxy form giving an employee controlled by the CEO—sometimes it is the CEO himself or herself—the right to vote their shares, or they just ignore the form.

So now the CEO and the executors have their own shares to vote and also the proxies sent in by dutiful shareholders who want to be responsible and have no idea of the power they are giving to the CEO.

It doesn’t take a lot of shares to actually control a public company. There is a widespread acceptance that a common benchmark for control is 10%, which means enough shares to elect the directors; but there have been occasions where even 3% was enough.

So after the Clinton reform, the CEOs and executives got even more shares and even more control.

And what about equity funds and hedge funds? They can buy a huge number of shares, enough to have a significant influence. These funds have been increasing their holdings in public companies since the 1980s. But as the graph shows, they don’t care about executive compensation. Most fund managers will vote for any CEO who will strip the corporation of its yearly earnings by paying the highest dividends for the benefit of the fund members and their own commissions. Many have no long-term interest in corporate fiscal health.

Need more outrage?

- In his bestseller, Capitalism in the 21st Century, Thomas Piketty gave us the evidence that the high executive pay, especially in the financial sector, that began in the 1980s was a primary driver of the economic inequality that began at that time. The resulting economic frustration is causing the rise of disenchanted voters looking for a savior in an outlier like Donald Trump.

- The financial sector executive pay is directly subsidized by the U.S. taxpayers. A full 30% of bank tellers are so low paid that they qualify for food stamps.

- To top it off, according to Fortune magazine, the highest paid CEOs actually run some of the worst performing companies.

The way forward

It’s impossible to remake the corporate structure and eliminate the proxy. All reforms that try to give shareholder control will continue to be totally ineffective. Some states have begun taxing corporations above a specified ratio, but that is likely to have very little effect.

The CEOs don’t care about how much tax their corporation pays. The tax will raise funds for the local government and ensure adequate salaries for the politicians and top administrators, but nothing will trickle down to the workers.

Even if the tax or other solutions reduced executive pay, none of that would result in better worker pay. The savings would be stripped out in dividends and buybacks.

The only solution is to give workers more power—and that will only come from supporting unions. The entire country has an interest in this. For, if executive pay decreased and worker pay increased, that would greatly reduce the present extreme of inequality that is causing the rise of the right-wing populist movement and its search for a leader who will bring it economic relief.