“Shine! Shine!” That cry rang out in downtown Waterbury, Conn., in the mid-1950s. A group of working-class youth, shoeboxes in hand, plied their trade, usually for a quarter a shine.

Little did they know, less than a century earlier and many years before that, a similar cry—”Sweep! Sweep!”—could be heard on the streets of London. Those youth, many just children, toiled under much more dire circumstances.

The movie, Mary Poppins, is a light, fun-filled fantasy. Sweepers pop out of chimneys. Dick Van Dyke sings and dances on rooftops.

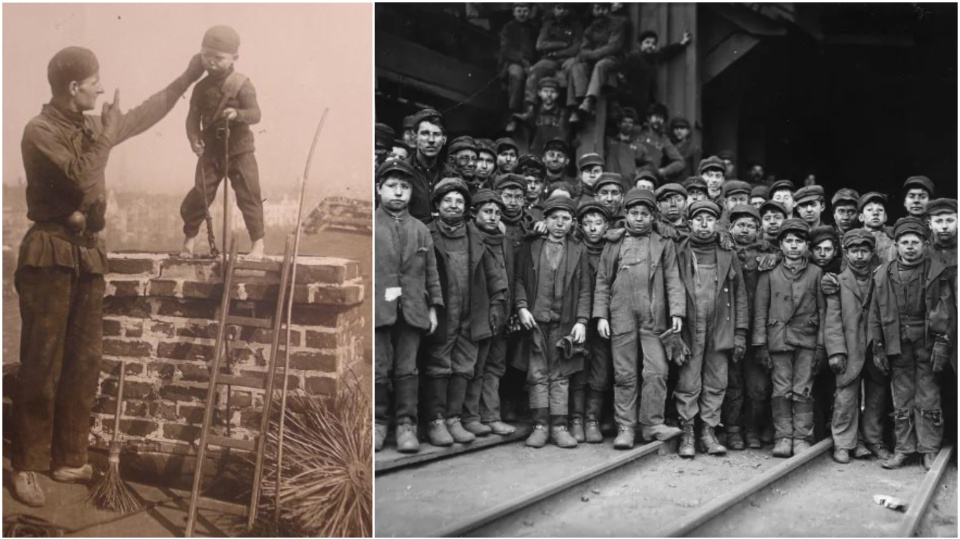

The real story behind chimney sweeps, as they were called, is neither light nor fun-filled. One worked in dark, soot-filled flues and chimneys. The caked carbon along those tunnels could very well be hot.

And it was all done by children as young as six-years-old. Burns and cuts were common. Some would die in those tunnels. Many would die from disease before adulthood.

Who were these children? Where did they come from? What parents allowed their children to do such work?

They were from uniformly poor, working-class families. Quite often a boy, occasionally a girl, was “sold” to a businessman. He would house the young sweeps under horrible conditions and provide them with all too little food. Orphans and children in poor/workhouses were also easy targets.

The little ones were purposely kept emaciated in order to fit into small, tight flues. A jingle, almost assuredly by the business class, was “Little Boys for Little Flues.”

A relatively new book casts a light on the more than two centuries of vicious, deadly exploitation of working-class children.

Infants of the Brush: A Chimney Sweeps Story, a 2017 novel by A. M. Watson, exposes what was not so merry in merry old England.

Just how vicious was this exploitation? The children had to strip to underclothes as they entered a flue or chimney. If they were new, they were often quite reticent about making the dark entry. The “boss” would stick a pin into their feet. If that didn’t make for a full entry, he would start a fire and let the heat drive the little ones upward.

The most dangerous houses were those with many flues over and above the number of chimneys. The wealthy owner would save money this way as it reduced the chimney tax. Unfortunately, this would necessitate many twists and turns in the flues. The chances of being stuck and suffocating were ever-present.

If a sweep came back short of the daily monetary goal set by the boss/owner, he was beaten.

The origin of sweeps goes back to the fire of London in 1666. When the wealthy rebuilt, displaying many chimneys was an indication of the extent of their riches.

The enclosures, and further privatization of land, drove peasant families into London and other major cities. Many of these families, left at bay to the vicissitudes of capitalism, would sell children into the hands of vicious sweep bosses/owners. Many sweeps would never see their families again.

The summer downtime in the sweep business was no exception to the exploitation. The youngsters were then typically employed to clean the streets of horse dung. Their toils and troubles were described by Frederick Engels in his 1844 book, The Condition of the Working Class in England.

In the 19th century, the call to reform the sweep exploitation of young children in England was gaining steam. Concurrently, there was the rise of a new movement calling for both the freeing of slaves and their equal treatment. At abolitionist meetings, in an attempt to split and retard the new movement, someone would raise, “What about the sweeps?”

In reality, there was a need for unity between the two movements. For example, slave children were used as sweeps in New York. It was African American children who suffered the same indignities, diseases, and early deaths as their counterparts in England.

The most effective law curbing the use of children sweeps was passed by Parliament in 1875. It required a police presence when child sweeps were employed. Even this last legal effort was not fully enforced. It was only the widespread change to oil and gas for heating that finally ended it.

Ripping children away from parents and relatives continues in different ways in different places. Immigrant families at the U.S. border have experienced separation. Despite the recent Supreme Court ruling affirming the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), Indigenous children are still four times more likely to be put into foster care in their first court appearance at a child welfare hearing than white children.

And in state after state across the U.S., Republicans are rolling back child labor laws to provide cheaper labor for the owners of restaurants, bars, slaughterhouses, and more.

Watson, the author of Infants of the Brush skillfully based the core of this historical fiction on English case law, Armory v. Delamirie, a case dating back to 1722. In that situation, a young sweep found a jewel. He brought it to a goldsmith’s workshop to be evaluated. The goldsmith’s apprentice promptly stole the jewel from the youth.

The case resulted in the “finder’s keepers” law involving personal property. The law is still with us today. Even with a successful ruling, it is doubtful the young sweep was able to keep the valuable jewel. All monies went to the owner/boss.

What hasn’t been resolved generally are the private property laws that ensnared these children. Here’s what one self-interested private property owner—Lord Sydney Smith—had to say about the effort to reform or end the use of children in the chimney sweep trade in 1847:

“Such a measure we are convinced from the evidence, could not be carried into execution without great injury to property.”

In 2023, the class whose self-interested profits flow from exploitive property, are desperate to maintain their advantages. Promulgating war is its mainstay. Stopping that class from its fascist, iron heal solution for dealing with threats to its profits is the first order of the day.

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today. Thank you!

Comments