WASHINGTON—The Black Youth Project 100 (BYP100) D.C. Chapter and the Claudia Jones School for Political Education, based in Washington, D.C., came together online on the evening of May 18 to co-host an event regarding the twin ideas of freeing political prisoners and prison abolition. The event featured elders from the Communist Party USA who were involved in the United Committee to Free Angela Davis and the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression to talk about experiences in those campaigns and also their own personal experiences around criminalization of youth, mass incarceration, and related topics.

BYP100 D.C. organizer Nnenna Amuchie led the conversation by first giving the history of the Washington, D.C., jail from when it was first built in 1872. Notably, during the 1972 Attica prison uprising that happened in New York, inmates in the D.C. Jail followed suit by taking guards hostage and presenting their demands. Amuchie’s timeline concluded with how D.C. officials have recently approved a $700 million bill, on the grounds of “unsanitary, inhumane” conditions, to construct a new jail. BYP100 DC organizer, Naiya Speight-Leggett was the moderator for the discussion with the panelists.

The presentation sparked discussion among the audience about whether, regardless of a new facility, jails are humane and sanitary to begin with. The racial and health demographics of those behind bars were also a key theme. As of 2018, 89% of those incarcerated were Black, 59% met criteria for a chronic health condition, 54% met criteria for a substance abuse disorder, and 35% indicated a history of serious mental illness.

Now, in the time of COVID-19, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) guidelines suggest physical distancing in order to slow the spread of the virus. Jails, prisons, and immigrant detention facilities do not lend themselves to inmates physically distancing, leading to calls to release inmates who are at high risk throughout the country.

In the D.C. Jail, 186 inmates have tested positive while one person has died; another 791 are in quarantine (which means isolation in solitary). In the D.C. youth jail, ten youth have tested positive, while 44 are in quarantine. BYP100’s #NoNewJailsDC campaign demands:

-

That D.C. officials release all people from D.C. Jail and help stop the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

That D.C. officials stop the flow of people into the jail during the COVID-19 crisis. Incarceration carries an unacceptable risk to incarcerated people and to public health, and no one deserves a death sentence in a pandemic.

-

Health care and dignity for our most vulnerable communities: a) Guaranteed free health care access for anyone remaining in the jail. b) Eliminate punitive measures, such as solitary confinement or further restrictions on people’s mobility, which are not a replacement for adequate healthcare measures. c) Eliminate forced labor for incarcerated people in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

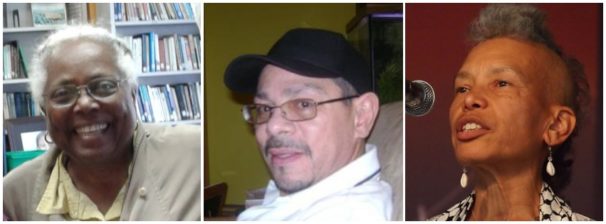

The next segment of the program focused on the panelists, with a leading introductory song by Luci Murphy of the D.C. Labor Chorus, “We Who Believe in Justice Cannot Rest Until It Comes,” also known as “Ella’s Song.”

Cassie Lopez, who was a former member of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the W.E.B. Du Bois Clubs, and then a lead organizer in the Free Angela Davis campaign in the early 1970s, spoke of her youth when she was in Detroit. She also touched on experiences around police brutality, specifically about her father, who was arrested for being a suspect in a robbery, which terrified her as a kid.

“I always thought I had to fight injustice,” Lopez said. “I joined my first picket line at ten years old, and at 75, I’m still joining picket lines and organizing. Capitalism is not working for us and it never was working for us.”

She spoke about her time as a key organizer for the original 1968 Poor People’s Campaign and the March on Washington and when eventually heard of Angela Davis’s case. She went to some meetings of the Nitty-Gritty Club in North Oakland, Calif. (at the time, an all-Black club of the Communist Party), and said that when Davis was underground hiding from the FBI, “The Communists protected her so she would not be murdered.”

Lopez and others eventually opened up a small headquarters in North Oakland, not far from where the Black Panther Party organized and ran a Free Angela Campaign. Henry Winston, then CPUSA national chair, pushed for bail for Angela so it could broaden the movement to free her. Eventually, Roger McAfee, a dairy farmer in California, paid her bail, ending her 16-month incarceration. The Communists and others stood guard for his family.

Lopez’s particular role in the campaign was organizing the Black community to get involved, and they held marches and concerts to fundraise for the cause. She said she visited the jail every day to visit Angela and made sure she was getting the medical treatment she needed. She added that “one of the most beautiful architectures was the jail where she was incarcerated, and inside it was still a jail where people were incarcerated.”

Lopez elaborated on the struggle in that campaign, speaking of the spirit of Black people at the time, and reminded the audience that there were millions of people around the world, especially in the socialist countries but including capitalist ones as well, who supported Angela’s freedom.

Jaime Cruz, Jr., who was involved in the Young Workers Liberation League and the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression during his youth, spoke of the Wilmington Ten case in 1971. The Wilmington Ten were wrongfully convicted of arson and conspiracy after a grocery store was firebombed.

Rev. Benjamin Chavis, Jr., was a part of this group, who were sentenced to a total of 282 years in prison. Cruz joined the campaign in the mid-1970s and recalled with joy the fact that Amnesty International got involved in the case in 1976. The convictions were eventually overturned due to the violation of the defendants’ constitutional rights, but not before they spent almost a decade behind bars.

In the NAARPR, Cruz was involved in organizing and leafleting and was deeply involved in other cases involving Puerto Rican political prisoners. He worked with the solidarity committee in freeing the Puerto Rican political prisoners and for the decolonization of Puerto Rico. Cruz also organized youth around legislation regarding youth unemployment, which was 15% nationally at the time and higher for nationally oppressed minorities. He joined the Venceremos Brigade in Cuba, spent ten weeks there, and learned more about what a socialist project looks like. At the time, he was relatively idealistic and believed “the revolution” was around the corner.

The current climate

A question was posed to the panel asking what the current climate of prisons in the U.S. demands from organizers today. “We need to go deeper into our communities…organize around the issues like jobs, housing, and education,” Lopez responded. She also spoke of organizing her students into the group Youth Power, which gets students to the city council to speak out for their rights.

Cruz spoke about how people need to be educated, and how youth are the “shock troops” and can bring about the change in a short period of time. He wants to inculcate that spirit of struggle and solidarity to take this world back for “ourselves”—the working class and oppressed. He further spoke of gentrification and how it is affecting urban demographics: The communities that are abandoned by those with higher incomes are being over-criminalized, suffering as a result of public schools defunding and the increase in housing costs. “We’ve always been fighting back, and that is the history we need to capture and share with people, so they feel empowered,” he said.

The question of how should youth communicate with their elders in the movements for social change was also taken up by the panel. Lopez spoke of how Black elders have all too many experiences with the criminal justice system. She also told about how her grandson was thrown on the hood of a cop car and how they got the community to stop the police from harassing him.

“Elders are worried about the future of their youth, and they need some kind of organization that will speak to that need. It’s one thing to say ‘abolition of prisons’, but we need to be able to keep our kids out of the jail,” said Lopez. Jaime Cruz added, “There is a need for a ‘daycare center’ for the elderly to take care of each other, to bond and deal with loneliness, and to connect to issues like abolition.”

Lopez ended talking about the need for unity. “In terms of resolve, we need everybody on board to support some of these issues being espoused. We need to all stand together around the issue of justice of our race, the social upliftment of Black people is a major agenda item…. The one thing that makes it complex is that we become distant among ourselves in our own community…. Neighborhood building is important. You cannot be an activist without the community being part of you and you being part of your community, so people know you.”

The event closed with another song by Luci Murphy, “None of Us Are Free,” which was recorded by Ray Charles and written by Brenda Russell.