On Friday, June 17, the Oakland A’s will hold their second annual “Glenn Burke Pride Night.” The A’s were the first major league baseball team to hold a “Pride Night” recognizing Burke as a transformational figure in the struggle for equal rights for the LGBTQ community. (The Los Angeles Dodgers, the first team he played for, finally celebrated a “Pride Night” dedicated to Burke on June 2.)

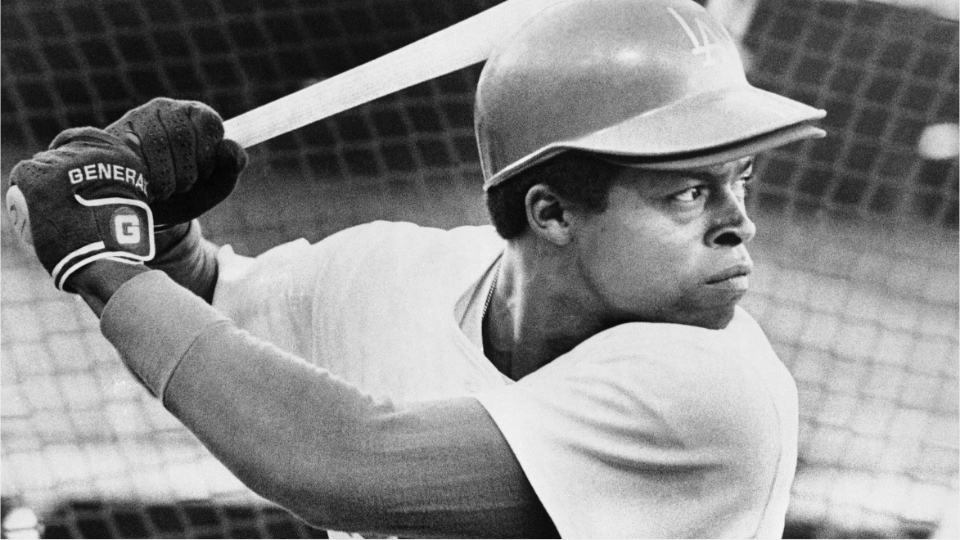

Who was Glenn Burke? Andrew Maraniss’s superb biography, Singled Out: The True Story of Glenn Burke, gives a full and insightful account of the life of the first openly gay professional baseball player. Uplifting, yet ultimately tragic, we learn about an athlete equally skilled in basketball and baseball.

The first time I saw Glenn Burke was in 1970 at the TOC—Tournament of Champions—the Northern California boys high school championships. The TOC featured the top eight basketball teams from NorCal, and Berkeley High was undefeated entering the tournament. Their point guard was 5’10” Glenn Burke. He was so dominant that he made an impression on me, and I thought he could possibly end up playing in the NBA. (Oakland Tech had a pretty good point guard as well named Rickey Henderson.) Berkeley High won the tournament and Glenn was named the Northern California Player of the Year, averaging 23.5 points and 11.5 rebounds per game.

At the playgrounds in Oakland and Berkeley, and in midnight pickup games against college players at Cal’s Harmon Gym, Burke continued to hone his game, and the University of Denver offered him a scholarship. But the cold weather didn’t agree with him, and he returned to the East Bay. He played hoops at two community colleges, and at the third—Merritt College in Oakland—he excelled not only at basketball but baseball as well, and the Los Angeles Dodgers took notice. The 19-year-old Burke signed with them and he was off to their low minor league team in Ogden, Utah.

Ogden in 1972 was not the most welcoming place for African Americans. On one occasion, Burke sat in a largely empty restaurant for 30 minutes before a waitress took his order. Realizing that Glenn needed to face better competition, the Dodgers sent him to their Spokane farm team, where he hit .340. His continued success resulted in his being promoted to Waterbury in 1974. While there, Glenn proved to be ahead of his time. Teammate Marvin Webb said, “We used to practice this dance where you’d clap your hands up and down, the hand jive…. Nowadays, players have all these elaborate routines they do before games. Glenn and I used to do that in 1973 and 1974.”

Burke was not afraid to be in the spotlight. He instigated a brawl with the Quebec team where he punched their pitcher, and a number of players were almost knocked out. This was hardly the stereotype of a submissive gay person that had dominated American society for years.

In the offseason, Glenn had his first gay relationship with a former teacher. “For the first time,” Maraniss wrote, “he affirmed his sexuality and felt the rush of falling in love. ‘This was who I was,’ Burke recalled, ‘the whole me at last.’”

On April 8, 1976, Glenn was called up by the Dodgers. Second baseman Davy Lopes, whose injury prompted the Dodgers to promote Burke, said that he had “unlimited potential.” Coach Jim Gilliam said, “Once we get him cooled down a bit, we think he’s going to be another Willie Mays.” Burke played well, but when Lopes was healthy again, he was sent back down to Albuquerque.

On June 2, Burke returned to Los Angeles and soon proved that he belonged there. He had a terrific first five games, with 5 hits in 10 at bats and 2 stolen bases. Glenn was very popular in the clubhouse. He brought in a boom box, danced before games, and was a jokester who made his teammates laugh. “He was the most lively personality I ever covered in forty-five years in sports,” journalist Lyle Spencer recalled decades later. “It’s hard to even compare him with anybody. He was this electric personality.” Former major leaguer Tito Fuentes agreed: “I would describe Glenn as like a glistening mirror ball at a discotheque when the light hits it and all of these different reflections and colors flash all over the room.”

But rumor began circulating that Glenn was gay. Former teammate and now Houston manager Dusty Baker said, “He was the life of the party. He was the most fun-loving dude, and he could dance like James Brown or Michael Jackson… The girls would flock to him and ask him to dance. But at the end of the night, he’d go home by himself every time.” When Davey Lopes heard the gossip, he said “I don’t give a shit. He was an integral part of the ball club as far as I was concerned. He added a lot to the chemistry of the team, the way he could make you laugh.”

Burke increasingly felt the pressure of trying to keep his sexuality a secret. He later said, “Straight people cannot know what it’s like to feel one way and pretend to be another. To watch what you say, how you act, and who you’re checking out.”

It all came to a head when Dodgers executive Al Campanis met with Burke at the end of the 1977 season and asked him to get married. If he did, he would get a $75,000 bonus. Glenn recalled, “He also began to make it clear that my career with the Dodgers was in jeopardy if I didn’t follow through with his wishes.”

Burke was right. On May 7, 1978, he was traded to the Oakland Athletics. In the Dodgers clubhouse, Lopes confronted Campanis: “Glenn? Why? What? You traded our best prospect. Not to mention the life of the team.”

Unfortunately, his reputation followed him to Oakland, and the stress finally caused him to explode. At one game, he had been heckled by someone who called him a “fairy,” and Glenn had had enough. After the game, he confronted the man in the parking lot and almost choked him to death. And on June 4, 1979, after a poor game at the plate, he decided it was time to move on from baseball. But a few months later, Glenn decided to give it one more try.

Billy Martin, another Berkeley High grad, had been hired to manage the A’s for the 1980 season. Burke was ecstatic: “Billy’s style will help me. I like to fight, too.” But unknown to Burke, Martin was a virulent homophobe, and he was sent to the minors. Glenn had little success, and after 25 games, he quit baseball for good. Without baseball, Glenn began spending a lot of time socializing with other gay men in San Francisco’s Castro district and began playing in the Gay Community Softball League. But he was doing cocaine and it wasn’t long before Glenn had spent all the money he made playing professional baseball. So, what to do now?

Without baseball, Glenn began spending a lot of time socializing with other gay men in San Francisco’s Castro district and began playing in the Gay Community Softball League. But he was doing cocaine and it wasn’t long before Glenn had spent all the money he made playing professional baseball. So, what to do now?

Burke met Cloy Jenkins, who owned a resort for gay men in Guerneville, a town on the Russian River 60 miles north of the Bay Area. He moved there and began to get his life and his health back. He was persuaded by his boyfriend to go public with his story. Glenn appeared on NBC’s The Today Show, where he acknowledged his sexuality, hoping against hope that he might get another shot at the major leagues. But no team contacted him, and he slid back into an addiction to cocaine. A car accident that devastated his legs and six months at San Quentin for drug possession seemed to sap what was remaining of his will to live. And on May 30, 1995, 42-year-old Glenn Burke died from AIDS.

At Friday’s “Glenn Burke Pride Night” in Oakland, Burke will be remembered as a pioneer of the LGBTQ movement who saw his career cut short by anti-gay prejudice. While the majority of baseball fans undoubtedly don’t know Glenn’s story, if they read Andrew Maraniss’s biography, they will have a better understanding of the struggles of gay and lesbian athletes. They will also realize that at probably every game athletes and fans alike will do something that Glenn Burke invented: the high five.

On Oct. 2, 1977, Dodger teammate Dusty Baker crossed home plate after hitting a home run. Burke was there to greet him with his right hand raised up, prompting Baker to slap it. “Glenn gets the credit for that one,” Baker said. “He was from the Bay Area, and everything starts there before it gets to the rest of the world. It was a moment of jubilation. If he had slapped me across the head, I would have done the same.”

Comments