Jack London’s journey as a socialist and a writer is a story of dramatic ascent and tragic decline, one in which personal contradictions ultimately eclipsed profound political convictions. Born in San Francisco in 1876, probably the illegitimate son of the astrologer William Chaney and the spiritualist Flora Wellman, he rose from exploited wage labourer to the most widely read writer of his generation. His socialism arose from childhood poverty, casual employment, hunger, and back-breaking labour in a cannery, jute mill, and power plant—experiencing the exploitative logic of capitalism firsthand.

This education was crystallised during his time as a hobo in 1894. On what he called “The Road,” travelling with Coxey’s Army and enduring the horrors of the Erie County Penitentiary, London ceased to see himself as an isolated victim. In boxcars and around campfires, he recognised that most wanderers were casualties of social injustice, their numbers growing as capitalism’s contradictions deepened. It was here that he first heard people discuss socialism, Karl Marx, and Frederick Engels.

Upon his return to Oakland, London sought theory. Reading The Communist Manifesto confirmed what experience had already taught him: the reality of class struggle, the opposition between private ownership and popular interests, and confidence in the eventual emergence of socialism. At the same time, he immersed himself in a vast programme of self-education, reading widely in philosophy and natural science. His worldview took shape at the intersection of Marxism, Darwinism, and the social evolutionism of Herbert Spencer, alongside the ideas of Malthus and Nietzsche—tensions that would never be fully resolved in his work.

This fusion of lived experience and intellectual conviction launched London into his period of greatest power as an activist and writer. A committed member of the Oakland socialist local, he became a regular and unpaid lecturer, renowned for his ability to explain complex economic ideas with clarity and force. His ventures into literature became weapons for the cause. His immersive journalism, The People of the Abyss, delivered a searing indictment of capitalism, documenting starvation and misery in London’s East End and earning him legendary status within the international socialist movement, and inspired Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London (1933).

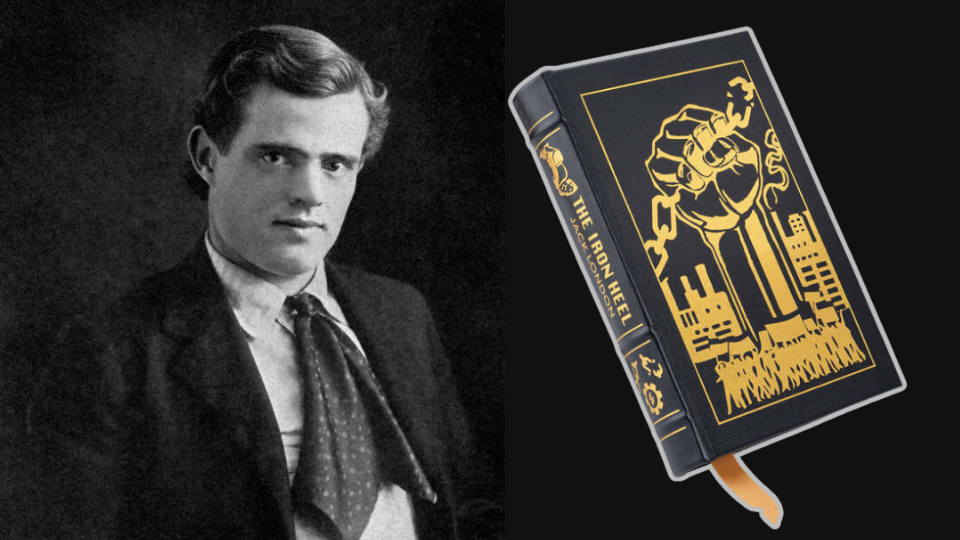

As his fame grew, London leveraged it without compromise. Elected president of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society, he embarked on a nationwide lecture tour, telling audiences at Yale and Harvard that revolution was not a distant prospect but an immediate necessity. He simultaneously produced a formidable body of socialist essays, collected in The War of the Classes, alongside polemical short stories such as The Apostate, a devastating account of child labour; Something Rotten in Idaho, a defence of framed union leaders; and parables like The Strength of the Strong. Widely circulated as pamphlets, these works equipped the movement with powerful arguments. The pinnacle of this period—and of London’s intellectual legacy—was his 1908 novel The Iron Heel, his most profound and prophetic creation.

Yet the success that gave London his platform also generated fatal contradictions. Wealth from books such as The Call of the Wild financed his expansive Glen Ellen ranch while drawing him toward increasingly commercial writing. The writer who had once championed proletarian internationalism now asserted the inherent superiority of the Anglo-Saxon “race” in his South Seas work. In line with this, he abandoned his political principles. Having celebrated the Mexican Revolution in 1911 as a heroic uprising, by 1914, he was serving as a war correspondent, defending U.S. intervention and insisting that the United States act as a policing power in Mexico.

This betrayal culminated in his resignation from the Socialist Party in 1916. Aligned with the forces he had once opposed, isolated by illness, debt, and disillusionment, London succumbed to the despair he chronicled in Martin Eden (1909). Nevertheless, he must be remembered as a brilliant voice of the working class—shaped by struggle, amplified by genius, and ultimately silenced by the corrosive contradictions of the system he sought to overthrow.

Animal fables

Since the fables of Aesop, and before that, authors have used the animal story to reflect human society. With the advent of imperialism, however, English-language animal allegory became a potent vehicle for exploring competing world views. Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book (1894) is one example, translating the logic of the “White Man’s Burden” into the “Law of the Jungle,” where Mowgli’s mastery over animals justifies colonial hierarchy, and the Bandar-log are cast as outcasts incapable of self-governance. In response, Jack London repurposed the animal story for a socialist critique, though tempered by social Darwinist overtones. In The Call of the Wild (1903) and White Fang (1906), the “law of club and fang” means a system of capitalist exploitation and alienated labour. Later, George Orwell would draw on these traditions in Animal Farm, creating a fable where animals serve as masks conveying his own political views—even more directly than in Kipling —directly transporting Orwell’s anti-socialist thinking.

The Call of the Wild

Though often read as a children’s adventure, The Call of the Wild carries a profound philosophical allegory. Buck, a mixed-breed St. Bernard–Scottish Shepherd, moves within a narrated world that simultaneously stages Darwinian struggle for survival and can be interpreted through socialist critique as well as through Nietzsche’s concept of the will to power. The Yukon functions as a microcosm of ruthless capitalism: the “club” represents coercive power, the “fang” brutal natural competition. Buck’s kidnapping and sale, culminating in the lessons of the man in the red sweater, depict dogs as a brutalised proletariat, whipped and driven for the profit of others, discarded when weak or old. Power struggles among the dogs, exemplified by rivalry with Spitz, expose tensions between collective solidarity and hierarchical dominance, mirroring London’s own conflict between socialism and belief in the survival of the fittest.

The buyers of the sled dogs, though working-class, enact the capitalist system. François and Perrault are competent, fair managers; Hal, Charles, and Mercedes embody capitalist incompetence, causing disaster. John Thornton stands apart as a model of benevolent authority, a master who rules by mutual respect rather than violence, akin to an ideal feudal bond, where Buck remains the guardian of Thornton’s safety and property. Buck’s bond with Thornton restrains his call to the wild; only Thornton’s death releases him fully to ancestral freedom and the wolf pack. The pull of the wild is accompanied by haunting visions of the “hairy man”—a primordial human ancestor. The Yeehats appear as a racist stereotype of the “savage Indian,” while Mercedes exemplifies London’s male supremacy thinking: hysterical, sentimental, and ineffectual, her failure contributes to the group’s collapse.

Buck’s journey is one of de-civilisation: from domesticated “everydog” to brutalised work dog, shedding domesticated traits as he learns the laws of violence and competition. Ultimately, he transcends even these struggles to become the mythic “Ghost Dog,” answering the call of the wolf pack. The harsh Yukon environment enforces this logic: snow signifies indifferent nature, the whip and harness the coercion of alienated labour, the club the state’s brute power, and the haunting “call” recalls primordial ancestry. In this way, London transforms animal allegory into a searing critique of capitalist exploitation, societal hierarchy, and the tension between individualism and collective solidarity, while also acknowledging the allure of a world beyond human law. The human society readers encounter in the novel, outside of the initial ‘civilised’ setting from which Buck is kidnapped, is a brutal order, from which only escape promises actual freedom.

White Fang

While The Call of the Wild stands as a powerful allegory in its own right, its argument is profoundly deepened when compared with White Fang. Whereas The Call of the Wild traces the de-civilisation of a domesticated dog into the wild, White Fang depicts the civilising of a wild wolf-dog into human society. This mirrored structure allows London to explore the same brutal systems—capitalist exploitation, the “law of club and fang,” and alienated labour—from opposing perspectives. In contrast to Buck’s journey, White Fang, who begins as “The Cub,” a wild predator, must learn the rules of human society first through violence and later through love. The “law of club and fang” is explicitly taught. White Fang’s first master, the Native American Gray Beaver, is far from benevolent; he demonstrates absolute power. White Fang accepts this law as necessary for survival, developing a deep sense of loyalty, responsibility, and the defence of his master’s property. In both novels, the canine protagonists accept their roles within human society and the demands of work, provided their masters are just and fair.

White Fang expands the hierarchy of human authority into a more detailed spectrum. Gray Beaver represents competent management, while Beauty Smith embodies brutal, sadistic exploitation. Against this, Weedon Scott emerges as the benevolent ideal, the John Thornton analogue. Scott’s compassionate authority demonstrates that even a creature brutalised by systemic cruelty can be nurtured and granted a protected space within a reformed, gentler order. In this way, Buck’s howl in The Call of the Wild expresses a world so broken that escape is the only option, whereas White Fang’s eventual domesticity represents the hard-won reward of surviving that world, albeit suggesting that obedience to a kind master is the key.

The Iron Heel

Among the Left, London is probably best known for his dystopia The Iron Heel, written at the peak of his activism (1905-1907). This novel is not only a singular piece of revolutionary fiction but also represents the culmination of London’s socialist thought. The Iron Heel is a foundational text of the dystopian genre, emerging as a direct response to the advent of the imperialist era. It offers a fierce class-based critique of monopoly capitalism, exposing the power of finance and industry—Morgan, Rockefeller, Standard Oil, U.S. Steel—and the corruption of press, law, and church in defending their interests.

London depicts imperialism’s drift toward dictatorship and the violent suppression of organised labour, warning against illusions in parliamentary reform or peaceful transition to socialism. He demonstrates how the growth of monopolies leads to an increasingly powerful oligarchy, wars, the crushing of workers and dissent, and eventually global wars. London’s understanding of the essence of his time is almost uncanny. Having studied the political climate and the bloody suppression of the 1905 Russian Revolution, he argued that the ruling class would never relinquish power voluntarily; it must be overthrown by revolutionary violence. He breaks decisively with the idea that socialism might be achieved through peaceful reformation, and predicts the revolutions that were to shake Europe within a decade (1917 / 1918).

More than that, London predicted the imperialist wars of the 20th century, several years before the outbreak of World War I. The novel is further a prophetic warning about the emergence of fascist dictatorships. London’s “Oligarchy,” or “Iron Heel,” is a brutal regime established by capitalist monopolies to crush a rising socialist movement, a dynamic that would later unfold in Italy and Germany, about twenty years before they arose. His concept of a ruling oligarchy of industrialists and financiers remains strikingly relevant today, illustrating imperialism’s persistent, ruthless enforcement of its hegemony against any dissent.

The novel offers a scathing critique of reformist politics, showing how attempts to change the system from within are futile, as the ruling class co-opts or crushes them. The fate of Bishop Morehouse, committed to an asylum for his beliefs, and the narrator’s father—a scientist who simply disappears—illustrates this reality. The Oligarchy’s tactic of splitting the working class by cultivating a labour aristocracy is also emphasised. Yet, London underscores the importance of international working-class solidarity: one chapter, “The General Strike,” depicts a coordinated work stoppage by U.S. and German workers that successfully prevents an imminent war between their ruling classes.

The Iron Heel is unique in its narrative structure. Presented as a manuscript discovered centuries later, after socialism has triumphed, it allows London to use foreword commentary and endnotes to satirise his present from a future, socialist perspective. The blending of narrative, factual material, and footnotes from the future creates dramatic irony—the reader knows from the outset that Everhard’s immediate revolution fails. Yet, these notes also assure us that, after centuries of struggle, a socialist utopia is ultimately achieved, giving the novel a tone of historical optimism.

The book also created a new type of hero in U.S. literature: the working-class revolutionary, Ernest Everhard, a composite of London himself and figures such as Eugene V. Debs and “Big Bill” Haywood. However, this emphasis on ideas comes at the expense of character depth: Everhard often functions as a “living mouthpiece” for London’s views rather than as a fully realised character. He is presented as a fully matured personality, with London forgoing a depiction of his intellectual and political development. Similarly, the narrator, Avis Everhard, evolves from a professor’s daughter into a convinced revolutionary, but her development remains largely functional to the novel’s ideas. Some characters are more fully realised, yet this is primarily a novel of ideas.

In London’s work, diverse and even opposing themes coexist without undermining the coherence of his vision. He wrote of class struggle, the downfall of the bourgeoisie, and the law of the jungle; of the perils of drink, prehistoric life, and the crafts of boat building and farming. The Übermensch stands alongside the slum-dweller, the gold prospector alongside the South Sea chief, the sailor alongside the workers’ leader. London was an incomparable storyteller, whose passionate engagement—whether in sympathy or outrage—spoke directly to his readers, especially ordinary people, many of whom first encountered literature through him. Their hardships were his own, and their hopes for justice his as well. Though his “law of the jungle” was later misappropriated to justify ruthless competition, he remained true to the cause to which he devoted his life, and the people whose fate he shared always understood him, despite contradictions in his philosophy. His major body of work, shaped by these contradictions, becomes a mirror of a pivotal developmental period in the U.S. nation, establishing Jack London as a pioneering literary figure in realist U.S. prose, whose recognition and influence extend far beyond his homeland.

As expressed in The Iron Heel’s foreword and endnotes, the novel envisions that a socialist society would arise only after centuries of struggle, through successive uprisings and repeated challenges to entrenched power, offering contemporary movements for justice both perspective and hope.

By the late 19th century, capitalism had entered a more aggressive, international phase, reshaping the global order. Technological progress and growing urban poverty foreshadowed World War I, while intensified colonial expansion created new struggles over resources and sparked further conflicts. Traditional humanist and rationalist frameworks were increasingly displaced by a power-obsessed anti-rationalism and anti-humanism, with nihilism emerging as a defining ideology of imperialist modernity—paving the way for Hitler and other fascist “solutions.”

Three works of art mark the emergence of imperialism, each capturing the global horror it would unleash while achieving lasting international recognition: Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893), Jack London’s The Iron Heel (1908), and W. B. Yeats’ The Second Coming (1919). Among them, London stands apart as the only socialist, and his dystopia is the first to depict the logic of imperialism in systematic terms, making it the inaugural dystopian novel of the imperialist era.

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today. Thank you!