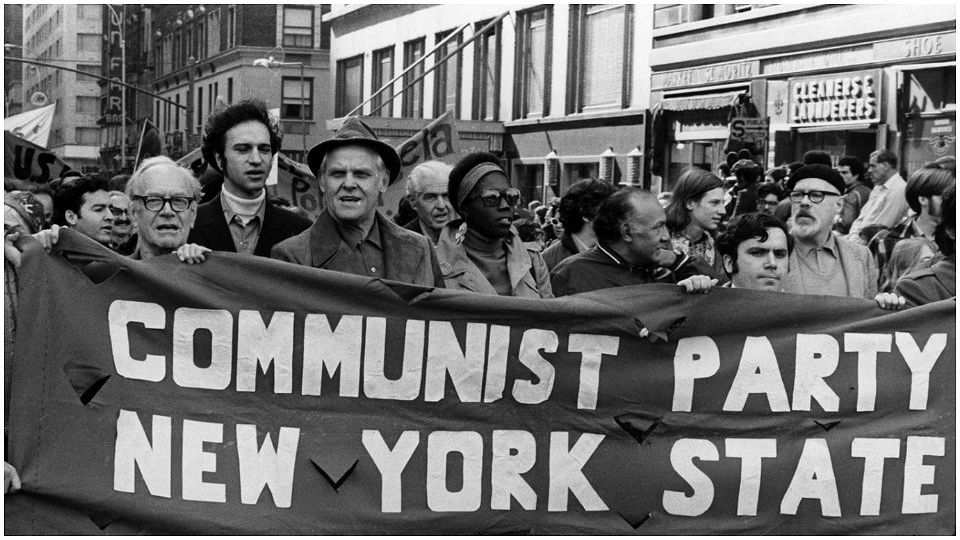

This collection of May Day memories from former Communist Party USA General Secretary Gus Hall (1910-2000) is an excerpt of an article that originally appeared in the Daily World newspaper on April 30, 1977. Hall shares flashbacks to some May Days in his own life—in his neighborhood, with his family, in prison during the Cold War, and more.

For some 90 years, workers throughout the world have been celebrating, demonstrating, and marching on May 1. On this special day, workers hold their heads higher and walk with a jaunty spring to their step. This is their day. In many small ways, they reflect a deep pride and unwavering confidence in their class. Some consciously and others instinctively feel that our class has the task of clearing the path, providing the main force, in the struggle for social progress.

On May 1, hundreds of millions of workers bask in the sunlit grandeur of the achievements, the victories, and the historic role of our class. It is the day when class conscious is on display.

The mass demonstrations are public expressions of the meaning of May Day to workers. But the depths of May Day’s roots can be more clearly noticed in the actions of individual workers who were not or are not in a position to take part in mass actions.

The class roots of May Day have a special meaning for me and can be best illustrated in these flashbacks.

Andy the Barber

For 40 or maybe 50 years, Andy was a barber in his one-man shop in the heart of a working-class neighborhood. His shop was open six days a week. It was also a center for working-class education.

On the first of May every one of those years, Andy did his special, unique May Day thing, and it was done with dignity and “class.” Andy, who ordinarily never wore a tie, would come to work wearing a bright red one. Not even the McCarthy Cold War hysteria stopped Andy from observing May Day. He would open his shop and put up the old sign, “May Day—No Work Today.” Of course, all his working-class customers knew that while Andy was not cutting hair on this day, the shop was open, including the door to his backroom apartment.

It was open for coffee and donuts and interesting and lively conversation. The Daily Worker and Communist literature were always present in Andy’s shop. Besides being a good barber, Andy was an excellent teacher, propagandist, and fighter. He used to say, “When a worker leaves my shop, he has much less hair, but much more understanding and class consciousness.” All one had to do was sit in his shop and observe to be convinced that what he said was true. Andy’s customers were politically advanced. They were his students.

During the McCarthy hysteria days, the FBI tried to harass Andy and his customers. For instance, a few would come and sit in his shop. But when they returned the second or third time, Andy decided to do something about it. He took out his razor strap and hung it on the wall next to the two agents. Then, with very deliberate, calm strokes, he began to sharpen his long razor. Years later, with a twinkle in his eye, he would relate how quickly the agents left his shop. Of course, everyone who knew Andy also knew that he would not harm a fly; the FBI agents were not so convinced.

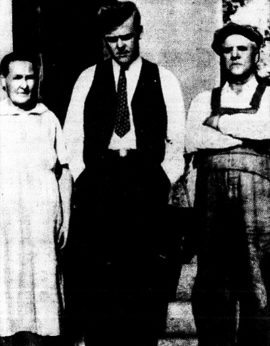

My father, Matt the Iron Miner

My father, Matt the iron miner and lumberjack, never worked on May Day. He lost jobs because of this. But for Matt, it was a matter of working-class principle. Instead of going to work, Matt would get a clean shave and put on his one good shirt without any fuss or planning, because in a sense May Day was a special family day. Susan, his wife and my mother, who was fully conscious of the political meaning of the day, would add an extra egg for the breakfast and a few extra pieces of meat to the stew for dinner.

But more than anything else, it was a day when the family conversation invariably drifted to political matters. It was a day when, more than at other times, Matt would talk about his experiences in strikes and other mass actions of the workers. As he related his experiences, it seemed that the workers had lost most of the struggles. But Matt never referred to them as defeats. He would mention with obvious pride how he had been arrested for his strike activities and with a mixture of anger and sorrow he told of the time when the National Guard broke into the homes of strikers and bayoneted them to death in their beds. They had been friends of Matt’s. After 25 years, he still refused to have anything to do with those who had scabbed during the strike.

May Day was also the day when socialism and the first working-class state, the Soviet Union, were the centerpiece of family conversation. Racism was also a subject that was discussed on this day more than others—racism and its effects on the nearby “Indian Reservation.”

In this household, there was a May Day atmosphere and a May Day family closeness. This was Matt’s and Susan’s way of instilling in their family working-class history and traditions, and pride in the working class.

These warm memories of past May Days are reflections of my family’s May Day roots.

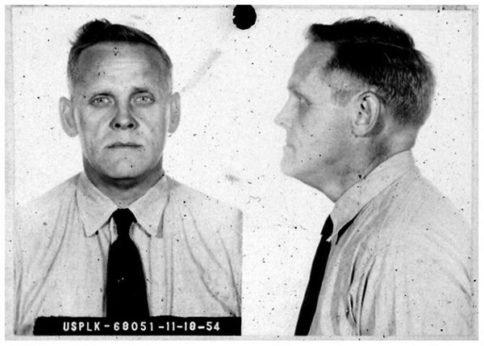

Bank Robbers

In jails and prisons, one gets to know many bank robbers. For most of them, robbing banks is not a profession. More than likely, it is a one-shot gamble. The fact that their address was Leavenworth Penitentiary was proof that the gamble did not pay off. Most of these prisoners came from poor working-class and farm families.

Possibly because some specific experiences before being sent to prison, or as the result of some reason, or as the result of some reading while in prison, some of these prisoners knew that for the Communist prisoners like me, May 1 had a special meaning.

There were some who wanted to express their sympathies and, in a sense, to join in and share this day with us. So one May Day, the prisoners who worked in the prison bakery secretly baked a cake for us.

On another May Day, a Black prisoner who had worked at the air field in Galveston, Texas, had smuggled some candy wrapped in red paper into the “hole” where were were—at the risk of being thrown into the “hole” himself.

And one year, a young bank robber from Cleveland, who had obviously given some serious thought to what he would say to us Communists when we met in the prison yard, greeted us with, “You…can’t observe May Day here in Leavenworth. But I’m convinced the time will come when the whole world will celebrate and honor the thoughts and ideas for which you’re in prison.” I must say it sounded much more forceful when he said it in what we call “prison lingo.”

Bristles and Brouhaha

There is one more May Day prison story I will never forget. About a week before May 1, there was a lot of commotion in the prison brush factory. Security guards were frantically rushing around. That evening, through the prison grapevine, I was told what all the commotion was about. The brush factory was getting hog bristles from the People’s Republic of China. The workers who unpacked the bristles knew they were addressed to the prisoners at Leavenworth.

When they opened on of the big wooden crates on this day, in addition to hog bristles, they found a hand-made sign that said, “May Day Greetings to Gus Hall.”

May Day for us all

May Day’s roots are in the class consciousness of workers—in the history, the experiences, the memories handed down through generations, the treasured traditions and pride in their historic role.

May Day is and will always remain a day of tribute to the Andys, Matts, Susans, and others—to the working class of our country who have sunk these roots.

The roots of May Day belong to every worker. They are forever a part of the past, present, and future of the working class.