The content streaming juggernaut Netflix has once again premiered a series that may help viewers forget about the current coronavirus troubles of the world while simultaneously reminding us of the systemic problems that helped deliver us to this moment in time. The docu-series How to Fix a Drug Scandal was added to the platform this month, giving a glimpse into the ever-present problems of the so-called ‘war on drugs’ through an exposé of the largely ignored drug laboratory chemists who ultimately help determine the fate of those charged with narcotics possession.

Through the stories of lab chemists Sonja Farak and Annie Dookhan—and the scandals their actions contributed to creating—the program sheds a light on the inequality that characterizes the justice system when it comes to drug use and possession. It will ultimately leave viewers a bit more enlightened and perhaps a lot more frustrated by the truths the series tells.

The program was produced by Alex Gibney (The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley) and directed by Erin Lee Carr (Dirty Money). The four-part series focuses on the misconduct of lab chemists Farak and Dookhan that sets off a chain of events affecting government officials, lawyers, and thousands of inmates. The two workers become symbols of a larger systemic problem within the judicial system concerning how people are persecuted under the law regarding drug possession.

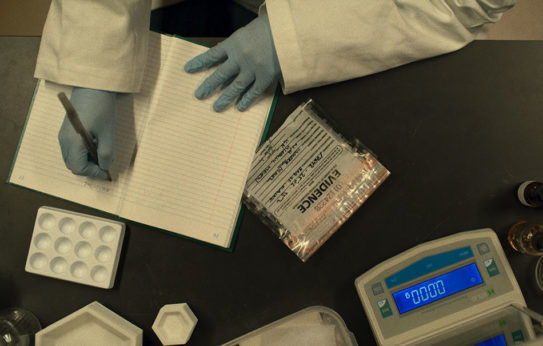

Farak was a drug lab expert in Amherst, Mass., who also happened to be a drug addict that used the substances she was supposed to test. She often conducted drug analysis while under the influence of these substances. A good chunk of the documentary takes a deeper look into her trial and the impact on those convicted of crimes based on her drug testing.

Dookhan was a chemist at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health lab who admitted to falsifying evidence affecting close to 34,000 cases. While the series takes a look at the lives of these women and what may have driven them to the actions they took, it is the response of the Attorney General’s office and government officials that gets to the real crux of the story on what happens when, instead of addressing systemic shortcomings, leadership buckles down in obstruction and cover-ups in order to “fix” the scandal rather than the system.

Government officials wanted to treat Farak and Dookhan as outliers who made bad decisions that were isolated instances. What the documentary unveils through interviews with lawyers and public officials, however, is that Farak and Dookhan are products of an environment that doesn’t care much for its lab workers and doesn’t concern itself with proper vetting—because it cares more about conviction results than quality of work.

This is what makes up a majority of the series, as defense lawyers fight to get their clients, who are serving time based on the compromised testings of Farak and Dookhan, some sense of justice in the face of law enforcement’s refusal to take another look at their cases.

This is not a flashy series with the quick jump cuts and comedic irony interlaced within the story that you sometimes find when documentaries try to appeal to mainstream audiences. What you get instead is a program that relies heavily on direct-to-camera interviews, archival footage, re-created court testimonies, and the journey to some sort of semblance of justice. It’s a riveting story that doesn’t actually need a lot of bells and whistles, but for those wanting a more fast-paced exploration, you may find this series lacking.

The lack of tantalizing action may also relate to the fact that when people think about the war on drugs, (a drug prohibition campaign led by the United States federal government with the proclaimed aim of reducing illegal drug use and importation into the country), we often think about law enforcement, lawyers, and those persecuted. Rarely receiving any attention at all are the lab chemists who test the evidence and testify in court about their findings, something that plays a major role in convicting those being charged. It isn’t a glamorous job with loads of television shows glorifying it in pop culture, but it is perhaps the most important aspect of the whole process that ultimately leads to the statistics concerning who ends up in prison thanks to this so-called war.

With that understanding, it would seem a given that lab chemists are workers who earn livable wages and that they are properly vetted and background-checked, since they have power to imprison so many. We learn in the documentary, however, that this is not the case at all.

We also learn in the documentary that, depending on your race and status, presumed innocence until proven guilty is a privilege not afforded to all.

In watching the program, viewers may become frustrated at the willful ignorance of government officials in not holding themselves accountable for the problems their negligence caused. Viewers may also become enraged at the fact that certain personalities in this tale end up with happier endings while others (read: working class people of color) have a harder time getting such second chances. It is a documentary filled with events that will have audiences discussing the intersectionality of race, class, and gender when it comes to the criminal justice system.

Drug laws and harsh sentencing has resulted in detrimental effects to communities of color. Studies have shown that people of color, particularly Black and Latino, experience more discrimination at every stage of the criminal justice system than their white counterparts, and are more likely to be stopped, arrested, convicted, sentenced, and chained with lifelong criminal records. Nearly 80% of people in federal prison and 60% of people in state prison for drug offenses are Black or Latino.

Research has also shown that prosecutors are two times as likely to pursue a mandatory minimum sentence for Black people compared to white people charged with the same offense.

This has lasting effects, as one in 13 Black people of voting age are disenfranchised by felony convictions that deny them their right to vote.

In the series, you only see a few glimpses of the nearly 50,000 people Dookhan and Farak helped to convict with their testimonies and compromised tests, but they serve as a dreadful reminder of the much bigger problem of inequality and bias in the criminal justice system.

At just close to four hours of television, the documentary only scratches the surface about the topic. How to Fix a Drug Scandal should make viewers angry about systemic injustice and government cover-ups, and hopefully that anger fuels more calls for progressive change.

Comments