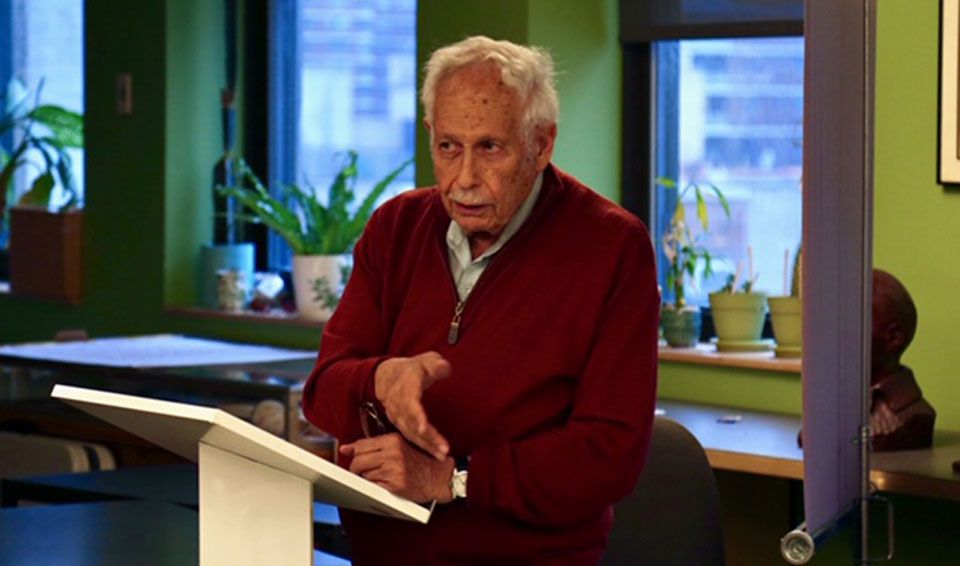

NEW YORK – “You know what today is?” Victor Grossman asks a gathering of 30 here during a stop on his book tour. He is coming to the end of his talk.

It is Victory Day, “the Anniversary of the liberation of Europe from fascism,” he says.

Seventy-four years later, we are sitting together in the NYC offices of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA).

Grossman is speaking about his new book: A Socialist Defector: From Harvard to Karl-Marx-Allee. The book tells about his life in the German Democratic Republic (GDR), a socialist country (East Germany) that existed after World War II from 1949 – 1990.

Grossman, 91, is the only person in the world with a degree from both Harvard University and from the GDR’s Karl Marx University. He is also the only U.S. soldier to have defected from the army and then lived in the GDR for most of its existence.

Grossman was drafted during the Korean War, but was stationed in Oberbayern, Bavaria, Germany. In 1952, he swam across the Danube river, was picked up by Austrian police, and taken, at his insistence, to the Soviets who then occupied that part of the country. The local Soviet authorities, soon after, took him by car to the GDR.

Steve Wexler — his birth name — had been a member of the CPUSA and other radical organizations during and prior to the McCarthy period. Now at his army base in West Germany, he received orders to appear before a U.S. military judge who would examine his “subversive” background. Under the notorious McCarran Act, years later found unconstitutional, he was eligible for years in prison. “That’s when I decided to take off,” he tells us.

After the war, Germany had been occupied by U.S., UK, and French troops in the West, and by Soviet troops in the East. With the support of the major capitalist powers, the Christian Democratic Union Party (CDU), under Konrad Adenauer’s anti-communist leadership, became the ruling Party in the West. The Socialist Unity Party (SED), formed when the socialists and communists in the East united, was the ruling Party in the GDR, which had the support of the USSR.

Grossman tells his audience “the first big step in dividing Germany” was when the U.S. and Adenauer rejected the Soviet offer in March 1952 of “a united Germany with free elections, and self-government, … [and] for all the occupying powers to get out, with one condition — Germany would have to be demilitarized and neutral.”

After this offer was turned down by the United States and Adenauer, the GDR then decided officially to proceed with the goal of creating a socialist society in the eastern part of Germany, in the GDR. This was just about the time Grossman arrived in the country.

Grossman, after working in a factory, had the opportunity to study journalism. He tells us about his first job after graduating from Karl Marx University’s journalism program. It was with a little newspaper called the Democratic German Report. “Its major mission was to expose the Nazis in West Germany,” he says.

“In every sphere, they were dominant,” — they “ruled the roost.”

“All 400 generals in [the West German) army had been Nazi Wehrmacht. … The old judges came back, who had sentenced people to death for listening to the BBC or for helping a Jewish escapee. … The old Nazi teachers came back.”

But Grossman says “the forces in back of the government” were most important. Specifically, he names Deutsche Bank and the big chemical complex, I.G. Farben. He highlights the Krupps, whose “family business” controlled Germany’s steel, artillery, ammunition, and armaments production, and Siemens, a multinational conglomerate producing everything from communications systems and electrical wiring to energy plants to medical devices and computers.

“The IG Farben heads built Auschwitz and ran Auschwitz,” Grossman informs us. “The Krupps … had 80 thousand slave laborers, of which I think about ten- or fifteen-thousand didn’t survive.”

Grossman reads an excerpt from his book, a quote from West Virginia Sen. Harley Kilgore, then-chair of the Subcommittee on War Mobilization of the Military Affairs Committee:

“Hitler and the Nazis were latecomers in these preparations for the war. It was the cartels and the monopoly powers, the leaders of the coal, iron and steel, chemicals and armament combines who had first secretly, and then openly supported Hitler in order to accelerate their ruthless plans for world conquest.”

In 1945, these “had all been thrown out [of the GDR]. … They never forgave the East Germans for that, and they tried for the next 40 years to win it back — until they succeeded,” he states.

These forces continued to rule in West Germany after the war, though IG Farben was split up into three daughter companies, including BASF “which grew … until it became the biggest chemical company in the world,” and Bayer “which also grew … until it was the second biggest in the world, but now it’s joining with Monsanto, which makes it the first.”

“Now,” Grossman says, “you have a neo-Nazi movement.” The Alternative for Germany is “the second strongest party after the Christian Democrats.”

Listening to Grossman talk, we find out a lot of surprising details about life in the GDR

Basic food staples stayed at the same very low price across the whole country from 1958 until 1990.

His rent also stayed the same, “never raised a penny. … Most people paid usually about 5 –10% of their income for rent,” he says, and “eviction was forbidden.” He says he never saw a single homeless person.

“Education was completely free up to postgraduate. … From upper-level high school [through] college, everybody got 200 [marks] a month which covered food and lodging and a little bit more.” He tells us that all students were “assured a job in their field.”

Childcare was also free, and women had “equal pay for equal work” although not many worked in the heavy industry, iron, steel, mining, or other higher paying jobs.

Pension age was 65 for men, and 60 for women and pensioners didn’t pay taxes.

“The gap between wealthy and not wealthy … was very limited,” he says. “One of the highest positions … the production manager of the [GDR’s] biggest car company … he got about 3,000 a month.” Unskilled workers would have been paid around 700, he tells us.

Grossman describes the theater, opera houses, films, directors, and actors in glowing terms: “the best in Europe, if not the world” … “magnificent” … “true masterpieces … especially the anti-fascist [works].”

“The entire atmosphere in the GDR was strongly anti-fascist, internationalist, against anti-semitism,” and there were all kinds of social clubs for people to participate in. The youth clubs were especially important. When the GDR ended, they were closed down, “leaving an awful lot of young people with nothing to do, often with very little hope for jobs,” and the “young fellows hanging around were prey for the Nazis who came in,” he says.

These successes in the GDR were achieved despite extreme challenges

“The GDR was not only much smaller than West Germany. It was incredibly poorer,” Grossman says, “with few resources.” All it had to develop its energy and chemical industries was brown coal “which is no damn good … it’s moist and full of sulfur and the processing of it stinks up the whole environment for miles around.”

At the end of the war, “East Germany had one steel mill. … West Germany had about fifty.” The GDR had to build up its energy sector, iron and steel industries, agricultural machinery, and shipyards from nothing.

Almost all the scientists and managers had Nazi connections, and went west, leaving the GDR with very few people to run industry. “They had to train their own new generation, but a lot of the professors had also been Nazis and had gone west.”

The GDR also had to pay war reparations to Poland and the Soviet Union. It bore the full brunt of reparations that the West Germans would not pay.

As a result, “it never had enough to invest in everyday consumer commodities.” Those it did produce, it had to export for western money to buy necessities. “West marks were considered four or five times the value of east marks,” which many places outside the GDR wouldn’t accept.

And all the while, West Germany was broadcasting scenes of wealth and abundance to convince GDR people of the wonders of capitalism.

The GDR also made many mistakes

There was some corruption, although Grossman says it was limited since “nobody could have stocks” or “make millions.” The leadership also “never really understood how to have a rapport with the public.”

Propaganda was “clumsy,” and “often boring,” painting a rosy picture when everyone knew there were problems. The teachers similarly were trained to convince the students that everything in the GDR was great and that everything in West Germany was horrible, but this created doubts in the children’s minds once they started watching TV.

Kids from left-wing backgrounds who asked difficult questions were “looked upon as almost provocateurs.” The vast majority of parents told their kids not to tell the teacher that they watched TV and to “[say] yes to everything the teacher says … which,” Grossman points out, “breeds hypocrisy and careerism.” The kids from right-wing families “resented then everything the teacher said, including the anti-fascist things, … [and] the anti-racist things and these were part of the base for the present right-wing youth development.

“Then three things hit hard,” Grossman says. One was keeping up with military developments in West Germany, which was “buying every modern kind of weapon.” Another was electronics, which threatened to make their machine tool industry obsolete. “This little country had to try and build up an electronics industry on its own.” Third was Honecker’s (the leader of the GDR from the early 1970s until the demise of the little republic in 1990.) promise, to provide every East German family with a modern apartment by 1990. These economic problems and goals were a huge economic strain on the country.

On top of that, Honecker’s economists made blunders, Grossman said. “There was a falling out with the Soviets with Gorbachev,” and when the wall came down in 1989, Honecker was ill with cancer, and the leadership was in disarray.

After the Berlin wall came down and the GDR was approaching elections, “West Germany offered everything, and especially the West Mark. … You got a hundred [west] marks … when you went over, to buy anything you wanted.

“An awful lot of people said, ‘We want a change. We don’t want to get rid of the GDR; we don’t want to get rid of socialism, but we do want a different and a better one,” Grossman says.

But, in the elections on March 16, 1990, “the Christian Democrats and their allies won the majority. … The remains of what was left of the SED had only 16 percent. The GDR officially ended on October 3rd, 1990.

“For many people,” Grossman recalls, “it did represent a [democratic movement] … when the wall went down” but it turned out it “was basically counter-revolution.”

“It has meant the Krupps, and the Siemens, and the Bayers (one of I.G. Farben’s daughter companies) have taken over again, and they have made Germany into a great power in Europe, perhaps second strongest in the world even, and a danger.

“This is an important day … especially in Berlin,” Grossman says. But “this time, to show it’s still a hot issue, somebody threw some kind of black smear element on top of [a famous anti-fascist] monument — it’s a statue of mother Russia mourning her dead. … It means that these fascist elements are still very strong and getting perhaps stronger.”

He laments a tragic irony: “On this very day, … this anniversary [of Victory Day], NATO is conducting mock exercises … rehearsing a new war with Russia.

“It seems to me,” he adds, “there’s now a four-part agreement between the United States, Saudi Arabia, Netanyahu [in Israel], and Bolsonaro in Brazil.

“Germany is part in, part out. … There are forces in Germany who would rather prefer trade with Russia than war with Russia, but they’re very powerful influences in Germany who want” — Grossman starts pounding his fists — “they’re in with the NATO.

“German politics is now to build up a European army which they dominate. … There are German troops in Afghanistan, in Mali, in front of Lebanon. … Economically and militarily, they’re spreading all over,” he warns.

“If you add the possibilities in Syria, … in Ukraine, and now I just heard that … the United States has taken over a North Korean coal ship, and … [in] Venezuela, … it seems so important to me that everybody … direct any movement they happen to be in — whether it’s [LGBTQ equality], or it’s Black Lives Matter, or it’s environmental … to link it together with the struggle to get peace and to end [these] maneuvers, and [these] trillions that are being spent on armaments.”

Victor Grossman’s full talk can be viewed on the Facebook livestream here. You can also access a fuller text description of his talk here.