Between 1865 and 1950, over 6,500 African Americans were lynched or massacred by white supremacist terrorists. Of those murders, 4,400 took place after the defeat of Reconstruction and restoration of the former slavocracy to power.

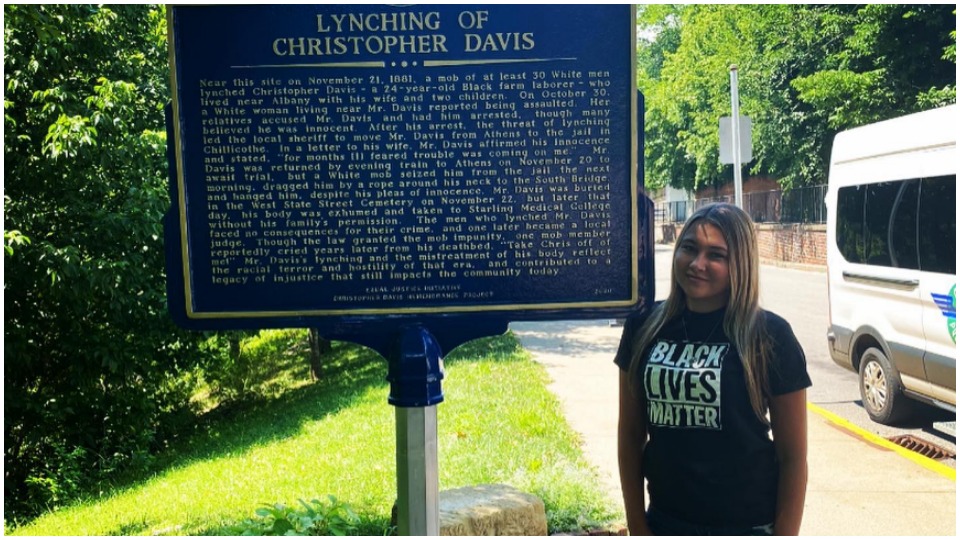

More than 80% of lynchings occurred in the former Confederacy’s 11 states, but over 300 took place in northern states. One of those gruesome killings was of Christopher Davis, a 24-year-old father of two. On Nov. 21, 1881, a mob of 30 white men lynched Davis in Athens, Ohio, home to Ohio University (OU). The community recently erected a plaque as a permanent remembrance of his murder.

During the long fight to free African Americans from bondage, Ohio was a center of abolitionist activity. Crossing the Ohio River meant freedom and the state had an extensive network of the Underground Railroad, including 300 roads, safehouses, and churches.

Including Davis, 15 documented lynchings took place in Ohio between 1880 and 1940. The Ohio Anti-Lynching League, a multi-racial organization initiated by radical Republicans and former abolitionists, led the campaign to end this heinous crime in the state, culminating in the passage of an anti-lynching bill in Ohio in 1896 after a spate of racist murders in 1894.

Ohio’s anti-lynching law became the model for other states and was used by the NAACP in the campaign for a federal anti-lynching law beginning in 1900. To this day, lynching is not a federal crime. Shamefully, the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act was passed by the Democrat-led House of Representatives in February but blocked in the GOP-controlled U.S. Senate by Sen. Rand Paul, R-Ky.

The acknowledgment of past injustice is critical for overcoming systemic racism and inequality and building a multi-racial democracy. The Christopher Davis Community Remembrance Project, a coalition of religious and community groups, waged a campaign to educate the public about Davis’s lynching. Working in collaboration with the Equal Justice Initiative, the coalition convinced OU to erect a plaque in Davis’s memory during the height of the Black Lives Matter protest in July.

What began as research into Davis’s lynching and the history of race relations in Athens turned into a doctoral thesis by Jordan L. Zdinak, a doctoral candidate in history at OU. Zdinak’s research was used in the campaign to educate the Athens community. People’s World interviewed Zdinak following the restart of in-person classes on Sept. 28.

PW: What motivated you to write on the topics of racism, slavery, lynchings, and segregation? Why, as a non-Black woman, did you choose this topic?

JL: Growing up in a diverse high school in Pittsburgh, Penn., motivated me to write on the topic of racism. I couldn’t help but notice systemic racism issues, whether it was treatment by teachers or police officers. I saw teachers treat the Black students differently by not providing the same attention as the white kids or not supporting or recommending them to be in the advanced classes. Police officers would closely scrutinize the Black kids at Friday night football games while white kids seemed to get away with a lot more.

I learned more about systemic racism as an undergrad and knew I wanted to pursue this topic as a graduate school historian. The subject of lynchings came to me through my advisor. She introduced me to a local coalition in Athens that was working to spread awareness about the lynching in Athens in 1881. It was something many people did not know occurred in the area, which is supposedly known for its good race relations due to its involvement in the Underground Railroad.

The coalition needed someone to do in-depth research on the lynching, and I was more than willing. It first began as an activity not related to my thesis, but I later figured since I was spending so much time doing this research, I might as well form it into a larger project. As a non-Black woman, I think it is essential to show that white people out there can act as supportive allies. Although we will never fully understand the obstacles Black Americans face, we can still offer support, whether it is through activism or spreading awareness and educating other white people about injustices in our society.

How did YOU come to put up the plaque honoring the subject of your thesis?

OU surprisingly readily agreed to put up the plaque. The Equal Justice Initiative agreed to pay for it, so we just had to get approval from the university for its placement site, and they were more than willing.

At the ceremony, we collected two jars of soil from the lynching site and had singers and speakers talking about our nation’s racial violence history. One jar of soil is in the Southeast Ohio History Center and is on display on the exhibit I created about Mr. Davis. The other is in Montgomery, Ala. at the National Lynching Memorial.

Was there any pushback?

We did have some backlash from the Athens Messenger, the local newspaper, when we had the ceremony commemorating Mr. Davis. Tyler Buchanan, the paper’s editor, wrote an article saying we should not have this ceremony because he believed Davis was guilty. Such a view echoed the problem with newspapers in the past, and which clearly continues in media today: They mostly automatically assume Black Americans to be guilty due to their skin color.

The lynching of Davis was justified in the press in its day. If Buchanan had access to my research, he would have known about the other newspapers further away from Athens that suggested Davis’s innocence of the accusation against him—the assault of a white woman. As a coalition, we decided not to respond to his ignorant message. We believed if we wrote a rebuttal, it would just draw more attention to his original document.

How do you feel about the success of your project in light of the recent BLM marches? How can others follow your example to create change in their community even if they are not academics?

I’ve always believed it’s essential for people to acknowledge past injustices and our nation’s history if we ever want to pave the way for a better future for race relations. The language on the marker recognizes the continuation of racial terror in this country and police brutality issues.

I think it is an achievement that the people of Athens now know this lynching occurred in their town, and they can work to make a better future and support the Black Lives Matter movement. I think creating a conversation about race and educating others will help create a better community.

Also, a lot of the members in the coalition were not academics. They found out about the lynching and wanted to spread awareness. We got into contact with the Equal Justice Initiative, which was able to help this vision come to life. If people are interested in making a difference, an organization such as this one is always willing to support new projects.

John Bachtell contributed to this article.

Comments