Pat Fry was a long-time activist, journalist, and leader in the working class, peace, solidarity, anti-imperialist, and left-wing movements in the United States. As a trade unionist, she had been a rank-and-file member and local official of the United Auto Workers (UAW) and worked for many years as a staffer of the Committee of Interns and Residents (CIR), a New York City-based health care union. She was a founding member, and co-chair from 2009-16, of the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism (CCDS).

She died at age 76 on June 28 in Traverse City, Mich., after a long struggle with cancer.

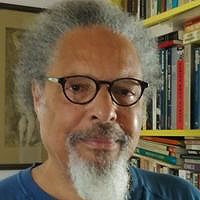

My own friendship with Fry goes back to the early 1970s in Detroit, where we were active in the local Marxist study group movement of the period. She was my successor as Detroit reporter for the Daily World, the newspaper associated with the Communist Party USA, and we maintained a close lifelong friendship.

Pat possessed a wealth of good humor and graciousness, as well as an incisive mind that was always open to new ideas and experiences. She was an ardent and always interesting conversationalist. Her resistance to dogmatic thinking and routinized philosophizing was not just an endearing quality; it also spurred her ability to work and make friends with a broad range of people of widely differing backgrounds and perspectives.

Patricia Louise Fry (born June 14, 1947) was the first of five children born in Detroit to Catholic, working-class parents John Henry Fry, a salesman who died in 1960 at the age of 36, and Anna Mae (Jones) Fry, a stay-at-home mom and a clerical worker who, at age 98, survives her oldest child.

Pat “came to the left from a moral Catholic background,” remembers Jim Jacobs, an old friend. She attended Benedictine High School in Detroit during the period of Vatican II, and the influence of Catholic social teaching of the time stayed with her.

During her senior year, 1965, the civil rights movement came home. A white woman from her neighborhood, Viola Liuzzo, had gone to Alabama to be part of the struggle and was shot to death in her car there by members of the Ku Klux Klan. “I was in awe of Liuzzo’s heroism,” Fry would later write. “Her racist murder shook me.”

“The civil rights struggle became my struggle,” she wrote. While a student at Eastern Michigan University (EMU), she joined the battle for open admissions and helped form a campus-wide human rights committee that called on Michigan’s Human Rights Commission to investigate systemic racism on campus.

She also fought Jim Crow in the North, picketing establishments that refused to serve Black customers, and collected data on landlords who broke the law by refusing to rent to Black people. She graduated EMU, “barely,” in 1970, she said, with a bachelor’s degree in education. She moved back to Detroit and soon got a job at Wayne County Community College as a clerical worker, becoming active in her UAW local. It was as a UAW rank-and-file member that she attended the first convention of the Coalition of Labor Union Women, held in Chicago in March 1974.

Fry plunged into the anti-Vietnam War movement. The following year found her in Cuba as part of the Venceremos Brigade, a group of mostly young people from the United States who went to Cuba to protest the trade blockade and work on the sugar cane harvest as an act of solidarity with Cuba’s effort to construct a socialist society.

She began her study of Marxism in the early 1970s as part of a bourgeoning movement of activists in Detroit from the campuses and the auto plants that assembled in groups to study the ideas and ideals of socialism. Pat joined one such group, the Detroit Organizing Committee.

Most of the members of these groups did more than just study. Fry was active in the fight against STRESS (Stop the Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets), the peculiarly named police unit that soon gained a reputation in Detroit’s neighborhoods as a terror squad whose victims were mostly Black, unarmed, law-abiding, citizens. The campaign against STRESS was a major contributor to the 1973 election of Coleman A. Young, Detroit’s first Black mayor. When Young disbanded STRESS, it brought jubilation to the city.

The election of the left-leaning Young administration was a period of lively debate on the entire range of social issues in the restaurants, bars, workplaces, classrooms, and living rooms of the city. Fry was in the thick of all of it.

Pat found herself part of a circle of young radicals around Harry Haywood, a legendary former leading Communist Party USA member whose book, Negro Liberation (1948), was the classic expression of the party’s early approach to Black Liberation. Haywood, whose ties to the CP ended as a result of the late 1950s crisis in the party, was living in Detroit. He was writing his autobiography, Black Bolshevik (1978), by then, and Pat became part of a group that worked on its production. She conducted interviews with Haywood, transcribed them, and typed the manuscript. The book has since become a classic of left-wing and African American political literature.

By 1983, Fry had joined the CPUSA, influenced by older radicals like Chris Alston, a Black community leader who had been part of the UAW organizing committee in the drive to unionize the massive Ford Rouge Plant in the early 1940s, and Al Fishman, a Communist who was a major Detroit peace activist.

Pat also credited me with being instrumental in her joining the CPUSA. I’d invited her to a 1983 meeting in Detroit where CPUSA activist and former Smith Act political prisoner Carl Winter gave a talk on the significance of the Young administration, then under attack from right-wing forces in the city and region. After hearing Winter’s presentation, Fry wrote, “I filled out a membership card joining the Communist Party that day.”

Within two years, she joined the staff of the Daily World as Detroit correspondent. One of her earliest stories was based on interviews with worker-participants in the great Flint GM Sit-Down Strike of 1936-37, in celebration of the UAW’s 50th anniversary.

Over the next several years, she chronicled a city and class in crisis. Plant closures, federal abandonment of aid to the cities, the onset of economic crisis and depression, and the increasing difficulty of union and urban officials to mount an effective response no matter how earnestly they tried, were all part of Fry’s beat.

These were also the waning days of the Cold War, and the ratcheting up of the peace movement, the fight against apartheid in South Africa, solidarity with the Palestinian people (which had a particular resonance in Southeast Michigan, with its large Arab population), and the effort to keep the United States from intervening against revolutionary and democratic movements in Central America. It was all found in Fry’s reporting in those years.

The end of the Cold War, with its crisis of Communist Party-led socialism, also brought crisis to the CPUSA, which manifested in the resignation of about one-third of its membership at the party’s 25th National Convention in Cleveland at the end of 1991. Fry was a founding member of the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism, an organization formed in the wake of that convention.

Pat moved to New York from Detroit to work full-time for CCDS in its national office, working with Charlene Mitchell, the former Communist Party leader who ran for president of the United States under the party’s banner in 1968, and who led the CCSD until a stroke in 2007 sidelined her. Fry served seven years as CCDS co-chair.

Fry joined the staff of the Committee of Interns and Residents (CIR) in 1999, an affiliate of the Service Employees International Union, as Director of Special Projects, retiring in 2012.

As the presidential election was ramping up in 2016, Susan Webb, an old common friend from Detroit and a former editor at People’s World, the successor publication to the Daily World, asked several writers, including Pat and myself, to share our reflections on the meaning of socialism in current times. This symposium took place during the Democratic primary season, during which Bernie Sanders placed the question of socialism and socialist politics at the center of public life in the U.S. for the first time in a century.

“There is no blueprint for socialism,” Pat wrote for that People’s World symposium. “Socialism cannot emerge from sentiment, ideology, or wish fulfillment. Socialism emerges because the working class, as it struggles around the crisis of everyday living, comes to recognize that it is a necessity.”

CELEBRATIONS OF THE LIFE OF PAT FRY

NEW YORK

Friday, September 22, 2023, from 5 to 8 p.m.

The People’s Forum

320 W. 37th St., New York City

DETROIT

Saturday, September 30, 2023, from 2-4 p.m.

Curtis L. Ivery Downtown Campus

Wayne County Community College

1001 Fort Street, Detroit

Comments