Frank Sheeran (Robert DeNiro) wanted to be respected. After all, who here doesn’t want that in some form? Legacies are born of it, along with resentment and bouts of regret.

Much like Sheeran, my father grew up during the post-war boom (the height of union membership), and after high school, he got a factory job, worked hard, and earned an honest living.

As a child, I vividly remember conversations around the dinner table where ideals such as “respect,” “solidarity,” and “duty” were synonymous with our family’s civic responsibilities and union membership—specifically, membership in the Teamsters.

Usually, the conversation would involve my uncle, a painters’ union member, listening to my dad ramble on about some bullshit disciplinary action he was handling: “Being chief steward was the best and worst thing to ever happen to me,” he said once, a long time ago.

The old man is retired now, after 35 years in the Teamsters union, and his health is in similar decline to that of Sheeran’s later years—lamenting some specific life choice here and there, consumed by the overwhelming dread of mortality.

Over the extended holiday break, we sat together for the first time in several months and watched Martin Scorsese’s impressive and expansive saga The Irishman (the title card reading “I Heard You Paint Houses”).

Now, before we dive in, I would like to take a moment and let you, the reader, know that I am not a film critic. My qualifications as a would-be-critic stem from my love of film, nothing more.

As far as this particular film goes, I enjoyed it. Would I say it’s great? A cinematic masterpiece?

Yes, and no.

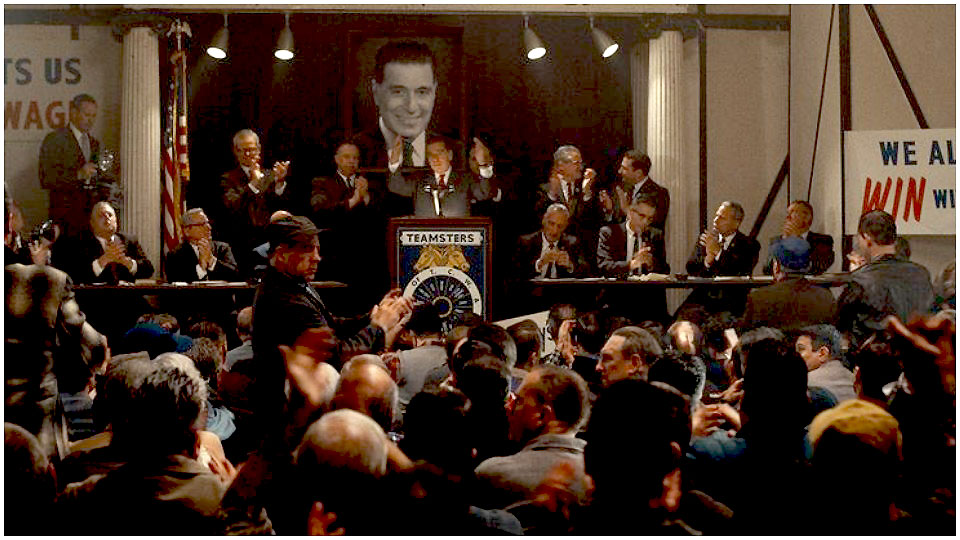

Scorsese did a masterful job approaching U.S. history through the eyes of the American Mafia, the “Mob,” La Cosa Nostra, and entangling some of history’s largest political and economic players and events: the Kennedys, Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino), crime boss Russ Buffalino (Joe Pesci), the Bay of Pigs, the war on organized crime, etc.

Pacino’s Hoffa—who got a thumbs up from my dad, who recognized him right away, despite his stroke—was a stellar performance, even with Pacino’s habit of elongating certain vowels and words. Joe Pesci, playing Russ Buffalino toned down his erratic behavior. And Robert DeNiro accurately portrayed an everyday character caught in two worlds: a forgotten soldier finding his way in post-war America, and a father consumed by a singular mission, protecting his family, unaware of the damage it would wreak. In merely seven words, Peggy Sheeran, played brilliantly by Anna Paquin, summed up all the emotion and pain caused by her father’s choices.

So why don’t I think it’s a full-blown masterpiece?

It had all the right elements: history, labor unions, politics, family drama.

But for all the things the film did well, it failed to portray the Teamsters union properly. We are thrown into this film from Frank’s perspective during the 1950s, which is all well and good. And yes, there was Mob influence within the Teamsters union (that we can’t deny). Yet, for all the trouble Scorsese went through to build up the relationship between Sheeran and Hoffa, he couldn’t spare a few minutes of this almost four-hour-long film to toss in a flashback as to why and how the Mob infiltrated the rank and file.

As Hoffa said in his autobiography, “Mob guys had muscle, and where in hell do you think employers got the tough guys when they wanted to break a strike?”

During the height of Teamster organizing efforts in the 1930s, companies, some of which are still in existence today, would go ahead and pay Mob tough guys to beat up and break any union activity or strike. They had no moral qualms with it.

Hoffa, on the other hand, just paid them off to stop breaking strikes and beating members. It wasn’t a smart decision maybe, but it was the only option left back in the day. It should also have been expected the Mob would take advantage of that inroad. Hoffa should have known better, but hindsight is 20/20.

And what’s the old saying: “Sometimes good guys gotta do bad things to make the bad guys pay.”

To be clear, I am in no way condoning the use of Mob muscle. I just wish the reasons behind why they were in the union to begin with had been explored a bit more.

I’ll also break with some actual critics and say some of my favorite parts came at the end, where Frank, lonely and broken, looks back at life, confesses (like a good Catholic), looks back again, and confesses some more. It’s not exciting, but it’s real, and it’s the realism that left me reminiscing about my life.

There is no ethereal ending to the film. The blurred line between fact and fiction is hard to distinguish but it’s there (occasionally), and overall it makes you feel something once the credits start rolling, and long after you’ve gotten up and off the couch.

Check out the books below to learn more about the Teamsters union, and the story of Frank Sheeran:

Hoffa: The Real Story by James R. Hoffa and Oscar Fraley

Revolutionary Teamsters: The Minneapolis Truckers’ Strikes of 1934 (Historical Materialism)

The Teamster Series (4 volumes)

Out of the Jungle: Jimmy Hoffa and the Remaking of the American Working Class

The Fall and Rise of Jimmy Hoffa

The Hoffa wars: Teamsters, rebels, politicians, and the mob