This is the first installment of a two-part series featuring interviews with the workers in the service, health, and other sectors who are still going to their jobs each day during the coronavirus crisis—the ones keeping our society functioning.

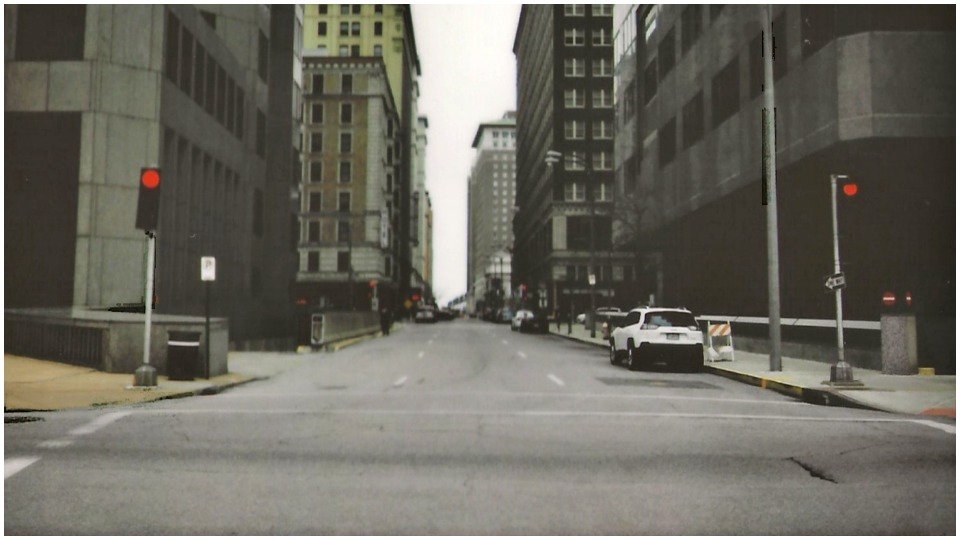

ST. LOUIS—The mood is uneasy. The streets are quiet and show their pain through the paint chipped curbs, cracked sidewalks, and boarded alleyway doors—there’s no foot traffic. Crowds no longer gather to hide the city’s worn-down façade.

Off in the distance, church bells ring. No one is listening. And soon it will be overtaken by the sounds of emergency vehicle sirens dashing off to care for troubled souls during troubled times.

This is a new reality. It’s the reality of life lived from a distance—at least six to 12 feet apart.

With the rapid spread of the COVID-19 coronavirus and in the wake of a bumbling and short-sighted response from Washington, D.C., communities have finally begun self-isolating at the request of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Stay home, read a book, walk outside (with precaution), and be patient. Those are the instructions, more or less. But not everyone can do that.

For those individuals working in the service sectors, some things have to keep going. Public transportation to and from work will be needed. Customers’ scant tips will be a necessity to weather this financial hell storm. Shoppers’ items have to be handled, scanned, and bagged. Health emergencies have to be addressed, even when personal protective equipment is in short supply. And on and on and on.

Their reality is this: “If we can’t work, we can’t feed or care for our own families.”

It goes beyond just the need for bread and butter. For many of these workers, they are the front line in the fight against the greatest health crisis of our time. It is something they know and take pride in.

A laughing child breaks a silent walk down city streets. A family of four have left their home for a quick morning walk—taking full advantage of the street’s emptiness.

Stocking up

Anxiety and fear accompany the spread of a viral pandemic, leading many to prepare for the worst possible scenario.

Crisis leads to a disorderly but methodical response: Stock up on basic supplies and hunker down.

So it was no surprise to find the grocery store parking lot packed full. Adults were pushing shopping carts overflowing with canned goods, toilet paper, boxes of dry pasta, and hand sanitizer while simultaneously dragging their kids behind them.

No one leisurely walks up and down the aisles, eyeing for their preferred brand. Instead, they all seem to be on a mission to get in and get out. Several shoppers sport the now common white surgical masks and blue non-latex gloves. Eye contact is avoided; no small talk takes place.

Towards the paper and sanitary products aisle, you see many unhappy faces, many cell phones pulled out of pockets to inform whoever’s on the other end of the line, “They’re out of toilet paper here too, damn it.”

The entire rack has been cleared, and no one can confirm when the shelf will be restocked.

Standing in the checkout line behind a grocery worker who’s off-shift, “finally,” with her cart full, I notice the exhaustion in the eyes of all the clerks.

“When did you get in today?” one shouts across the lane to another.

“Clocked in at 6:30 this morning,” the other replies, looking down at his watch. “Still waiting for my first break.”

It was now 2:00 p.m.

As I made my way to the register, I met Nicole. She was working a double shift and mentioned to her manager she needed to get off the line to call and cancel her son’s breathing treatment.

“I don’t know if you can tell from my eyes,” she said while scanning my bag of coffee, “but I’m exhausted.”

I asked her how things had been going at work since the government announcement pushing stay home with two weeks’ worth of food.

“Oh, it’s been crazy,” she said. “Today’s been a bit better than yesterday, but people have been in here constantly, and they’re not always the nicest…. They’re in such a rush they forget we’re only human, too.”

“What do you mean?” I ask.

“Well, they come in, fill up an entire cart with bottled water, and expect us to unload it, scan it, and then load it back up for them without any help.”

Nicole looks to be in her mid- to late-30s and is all of five feet tall.

She continued: “I already have a bad back from working in the warehouse, and this is just going to make it worse…. I can’t even get a thank you from customers most days.

“But we have to work, even if it’s forced overtime. People need to eat, and I need to pay the bills. I’m just telling myself today, and yesterday, and probably tomorrow, it’ll get better, and I’m happy to help people out in my way.”

The Bartender

Working in the “industry,” as the professionals in the food and restaurant business call it, comes with a few perks. Late nights with cash in hand, close friendships with other industry workers, and intimate knowledge of the best places to check out—knowledge only shared with friends, family, and good tippers.

Kate has worked as a bartender in an upscale sushi restaurant for three years. She’s been at the same restaurant for five years, working up from slinging plates to drinks.

We spoke briefly during her lunch break.

As more and more eateries and businesses closed to help stop the spread of coronavirus, she couldn’t understand why corporate had closed down her store.

“They sent out an email to the customers, letting them know about the precautions they were taking to make dining a safe experience,” she said. “But they didn’t say anything to us about it or what steps they would take to keep us healthy.”

Kate, 28, is immunocompromised and suffers from a genetic disease.

“I don’t mind coming in to work a shift. I take care of myself, wash my hands, and avoid touching my face…. Hopefully, I’ll be ok,” she said. “It’s just the people who come in to get a drink that I’m worried about; they’re coming into contact with me, and I have no idea where they’ve been or if they could have been exposed.”

She was scheduled to work an evening shift after her replacement called in sick.

“What pisses me off is that we’ve been so slow…” she continued. “At this point, corporate is making zero money off of staying open, yet here we all are.”

She laughed before saying, “And the few people that have come in complain that I don’t stay behind the bar the entire time they’re drinking. I was honest, and told them, ‘I am following CDC guidelines and staying at least 12 feet away from you.’”

Their reactions were stunned to silence, something she’d expected but was ok with.

“If we have to stay open, I’ll make sure those of us here stay safe until the city or state or whoever says we need to close.”

As her lunch break came to an end, I asked Kate about how the pandemic had affected her personally, if she’d learned anything from what’s happening.

“Well for one, to make sure I brew coffee the night before. I don’t want to put any of my barista friends at risk,” she said. “Also, I’ve never really been a political person, but with how things have been playing out, I’ve realized corporate and politicians don’t give a shit about those of us at the bottom. We deserve full pay and benefits during this crisis time—and I’ll vote whoever I have to out of office to make sure we’re not left behind ever again.”

Seeds of radicalism planted by a crisis—a small silver lining as society reflects upon how we treat one another.