SANTA MONICA, Calif.—The term “liberation theology” had not yet been invented in 1923 when Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw, a member of the socialist Fabian Society in England, where he lived, first staged his play Saint Joan. The historical drama is receiving a thrilling and radically re-imagined production by New York’s Bedlam theatre company, now at The Broad Stage in this city.

But already Shaw could see that Jeanne d’Arc—Joan of Arc, known as the Maid of Orléans—was centuries ahead of her time in using her radical belief in God to challenge the temporal authority of feudal kings and lords, as well as the power of the Roman Catholic Church which underpinned the feudal system. True to his socialist ideas, Shaw also used the Joan story to lay down intuitively persuasive arguments for feminism and anti-colonialism, salient themes that were in the air as Shaw wrote.

(In 1918, women over the age of 30 who met minimum property qualifications became entitled to vote in the United Kingdom; equal voting rights for women over the age of 21 came only in 1928.)

Shaw was already interested in the Joan story, studying the substantial transcripts of her trial, but in 1920, Pope Benedict XV canonized her as a saint of the Roman Catholic Church, tacitly accepting the French people’s adoration for her as a national savior and in effect recanting its almost 500-year-old excommunication and execution of the young peasant girl-become-soldier. That propelled him to pursue this project. Saint Joan is considered today one of Shaw’s most successful and popular plays, among the more than sixty that he wrote. Two years after Saint Joan premiered, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature 1925, living another 25 years as a laureate.

Shaw’s plays are known for their intellectual weight and the quick-wittedness and sparkling repartee that most characterize the comedic genre. Although these characteristics also mark Saint Joan: A Chronicle Play in Six Scenes and an Epilogue, it is sometimes referred to as his only tragedy (burnings at the stake being not ordinary fare for laughs). Yet the play has no villains as such, and does contain considerable humor at the expense of the privileged castes. As Shaw wrote in a preface to the play,

“It is…what normally innocent people do that concerns us; and if Joan had not been burnt by normally innocent people in the energy of their righteousness her death at their hands would have no more significance than the Tokyo earthquake, which burnt a great many maidens. The tragedy of such murders is that they are not committed by murderers. They are judicial murders, pious murders; and this contradiction at once brings an element of comedy into the tragedy; the angels may weep at the murder, but the gods laugh at the murderers.”

Perhaps it’s simply more accurate to say that the play is a tragedy of human nature. Hannah Arendt’s expression, “the banality of evil,” may be apt.

Shaw does not portray Joan’s trial as just, according to modern principles of secular jurisprudence. Yet it was conducted with far more reason than many trials in his own day (as in our own!) where the fundamental crime can be reduced to poverty. In the 15th century if a woman arose claiming to be a direct conduit of God, through the voices and visions she experienced, that was a heresy, if not witchcraft and deviltry, that the Church could not permit to go unpunished. Shaw understood the folly of expecting humans to step out of their known world into a set of social arrangements that would be many centuries off into the future. Today a person presenting Joan’s symptoms might be diagnosed with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia.

The story of Joan takes place during the long Hundred Years War, actually more a series of wars and skirmishes than a single event. English soldiers have occupied parts of her French homeland, and she presents herself to the Dauphin (the heir apparent) with her divinely inspired mission to get a horse from him and the charge of a battalion. The French soldiers lacked real fighting spirit and, struck by her self-confidence and charisma, Charles agreed to her request. She immediately set about defeating the English troops at Orléans in 1429 and went on to further victories.

Joan’s guiding philosophy was simply “France for the French, England for the English.” Apart from being a feminist icon before her time, she came to be a national symbol in an epoch when the Church presumed supranational authority. She was an early proponent of nationalism, which historically Shaw recognized as an advance in human consciousness, and by trying to kick the English out of her country, she was, in modern terms, anti-colonialist. She fought not for her king but for God and freedom. And it would be Joan who crowned the new King Charles VII of France at Notre Dame Cathedral in the city of Reims.

The play is three hours long—quite long enough for a dissertation on ideas without a great deal of dramatic action—and of course Shaw ignores the fact that England was also conquered by the Normans (remember 1066?). The Normans were never expelled. Quite to the contrary, we owe our rich, exuberant English language to the unique conflation of Anglo-Saxon dialects with medieval French. For centuries the steady intercourse across the English Channel made France almost as much part of England as England part of France.

But Joan was not thinking about such questions. In challenging the Church she also anticipated the Protestant Reformation, which rejected Church abuses and re-imagined that a person’s relationship to God did not necessarily depend on the intercession of the priest and the ecclesiastical hierarchy. To the Church, loyalty to the “nation” sounded anti-Catholic and anti-Christian. We get the sense—Joan even hints at it—that we are poised at the outset of a new, wider era in history.

In short, although the Church, the monarchy and the lesser nobility had their own conflicts and opposing interests, by going up against all of them Joan was not simply an unformed rebel but a conscious revolutionary. Those are the aspects Shaw saw in her.

Once she had served her military and political purpose—even with miracles attributed to her—the French were more afraid of her than grateful. After being captured by the English at Compiègne, she was not ransomed, but tried and found guilty by the Church of twelve counts of heresy. Remitted to the secular authorities, she refused to recant the sins charged against her, and was burned at the stake.

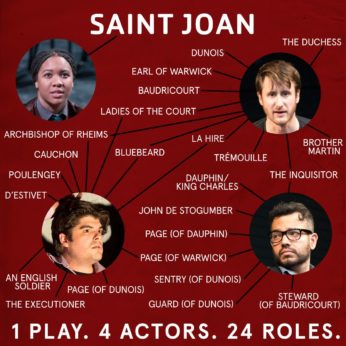

The play has some 24 roles, ranging in class from uneducated soldiers to petty nobles and indebted princes and kings, from lowly priests to archbishops, and deployed on both the French and the British sides. Even in good times, and even if you double-up a few roles, that’s an expensive production!

Bedlam’s solution is to pare down the cast to four players. The magnificent Aundria Brown plays Joan, and the other roles are divvied up among Aubie Merrylees, Sam Massaro and Kahlil Garcia, all exceptionally catlike in their astonishing agility and versatility. Eric Tucker directs, as he also does the same cast in a concurrent rotating repertory Hamlet. The set design, simple and utilitarian with a few props, is by John McDermott. The costumes and sound design are also by Tucker, who prefers modern casual street dress with only the occasional indication, such as a robe or head cover, to indicate rank or profession.

There is much to admire in such an essentialist approach: We focus on the text without distraction from gorgeous costuming or lumbering sets. Yet much is also lost in the process. Skilled as the actors are in adopting a different voice for each character, a distinctive walk or gesture, miss a single word (almost all of it barked at breakneck speed) and you’re liable to miss which character is speaking. Miss a couple of them in a dialogue or ensemble scene where the four actors are playing up to seven or eight roles, and you’re really at sea. The actors speak with American voices for the French roles, and British accents for the English, so that helps some.

There may be a method to Tucker’s madness. Many theatergoers will not be so familiar with the historical or invented personages Shaw introduces, nor precisely understand their particular part in the drama. What Tucker may be going for is to show all those forces—monarchy, nobility and Church—enthralled by Joan at first, then horrified by the popularity she has won and the threat to their power. In the third act, the trial, Joan occupies a well-lit spotlighted space center stage, but her accusers, both civil and religious, scurry back and forth in front of the stage on the audience level, along the side aisles and from the balconies in semi-lit areas or even in the dark house.

Then it becomes obvious that Tucker is no longer so concerned about individual characters and more interested in communicating that an amassed condemning world, including us in the audience, is aligned against the martyr. One could only think of the McCarthy hearings of the Red Scare period, with the klieg lights on the innocent subjects, the finger-pointing politicians and the compliant press. A “Christ” is sacrificed in every age.

Playgoers who already know Saint Joan will suffer less identity confusion amongst the characters and may follow the action more intelligibly. For first-timers, well, Shaw’s language and ideas are inimitable: It is not for nothing that next to Shakespeare he is regarded as the most prolific and most eloquent playwright in the English language. But critical continuity may be lost in the fog. In Act II some fifty or so members of the audience are seated on bleachers on-stage, and I envied their intimate proximity to the actors and the text. I wondered if the whole production would be more accessible in a smaller venue.

Aundria Brown’s Joan is excitingly memorable, and her companions most competent at their craft. This cannot stand as the definitive Saint Joan—nor does it pretend to.

Performances of Saint Joan and Hamlet continue at The Broad Stage through April 15 only. Tickets and other information are available at the venue’s website or by calling (310) 434-3200. The Broad Stage is located at 1310 11th St., Santa Monica 90401.

Comments