A circular economy is one in which products do not end up as waste but are instead repaired, reused, or transformed into new materials. This stands in contrast to the linear economy currently dominant worldwide—one built on extraction, production, use, and disposal. Despite the growing recognition of circularity as a sustainability necessity and the implementation of many circular economy initiatives worldwide, very few systems are truly circular in practice. Space debris—nonfunctional human-made objects orbiting Earth—starkly illustrate this contradiction, exposing the same structural failures that limit circularity on Earth. Thousands of defunct satellites, rocket parts, and metal fragments now circle the planet in orbits that are circular in motion but linear in design. Once launched, they have no way back because they were not engineered for retrieval, nor intended to be reused, recycled, or repurposed. Ironically, what appears circular from a distance is, in fact, a one-way journey to permanent waste.

Much like on Earth, the challenge in orbit is not only the loss of materials but also the growing risks posed by unmanaged waste. On the ground, discarded plastics, electronics, and toxic chemicals leak into ecosystems, pollute water and soil, and impose long-term costs on public health and infrastructure. In orbit, the dangers manifest differently but just as severely. Debris has become a high-velocity threat. We tend to imagine satellites moving in neat, parallel lanes around Earth, but orbital paths often intersect, and objects travel at about 29,000 kilometers per hour in low Earth orbit. When they meet at these speeds, even a screw-sized fragment can tear a satellite apart, splintering it into hundreds—and in catastrophic collisions, even thousands—of new fragments, compounding the threat. These risks are mounting fast, threatening systems that modern life depends on—from GPS navigation and weather forecasting to broadband internet, aviation safety, and disaster response.

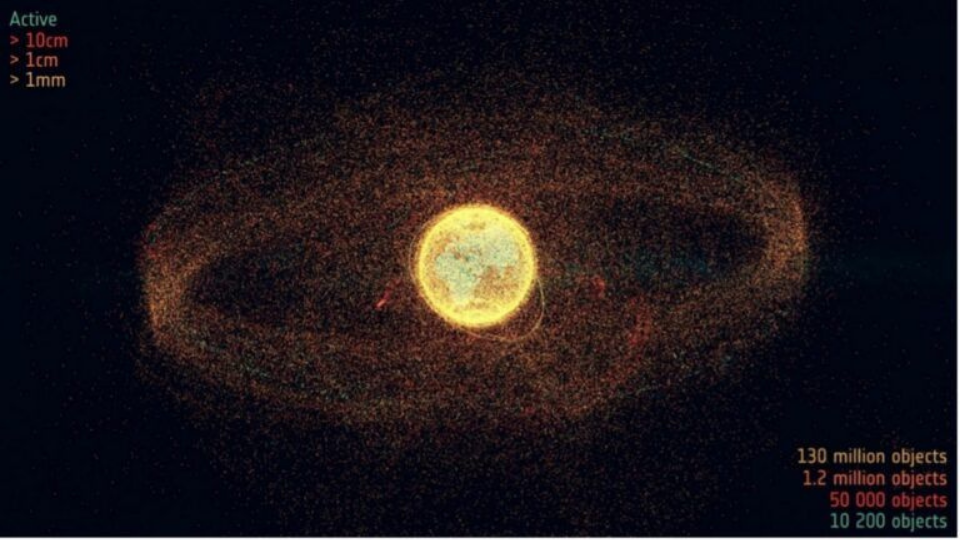

Since Sputnik 1 lifted off in 1957, objects have been steadily accumulating in orbit. Today, space networks track roughly 40,000 pieces circling Earth. About 11,000 of these are active satellites; the rest are junk. Yet these are only visible fragments. The European Space Agency (ESA) estimates that more than 1.2 million objects larger than one centimeter, each capable of causing catastrophic damage, are currently circling the planet. Despite decades of warnings, governments and private companies have continued launching missions with little plan for what happens after their useful life. The result is a growing halo of waste around Earth, and the trend is accelerating.

Space innovation is often celebrated as a sign of progress, yet its legacy of waste is overlooked. On Earth, too, technological advances—from electric vehicles and solar panels to smartphones and smart grids—are praised as a way to reduce emissions and environmental harm, yet the waste they generate remains largely ignored. Obsolete electronics, packed with rare earths and toxic chemicals, are increasingly difficult and costly to recycle due to complex product designs. Many high-value materials are lost, ending up in landfills or informal recycling sites across the Global South, where “cheap” recovery exposes communities and ecosystems to serious risks.

So, what can space debris teach us about the circular economy? Quite a lot. Space junk is the ultimate example of what happens when technologies are designed for use, not reuse, and when innovation races ahead of the systems meant to manage its aftermath. Orbit has become a mirror of our wider economy: filled with high-tech products built to perform flawlessly yet never intended to be sustainably recovered. It reflects not only our ingenuity but also our persistent failure to take responsibility for the full lifecycle of what we create.

Space junk offers at least three lessons about why circularity breaks down, in orbit and on Earth alike.

Design without end-of-life in mind creates lasting waste. Satellites, rocket stages, and fragments were never built for recovery, reuse, or safe disposal; not because it was impossible, but because it was never required. Doing so would have added weight, fuel, and cost to missions that prioritized performance and reliability over long-term stewardship. Once launched, they become “forever products.”

On Earth, we make the same mistake. Devices are engineered for sleekness and low production cost, not for disassembly or repair. Policymakers have only recently begun to address design as a driver of waste, recognizing that circularity cannot be achieved through recycling alone but requires products to be built for reuse, repair, and material recovery from the start. Modern electronics illustrate the point: valuable materials such as gold, cobalt, and rare-earth elements remain locked inside glued and soldered components, making recovery economically unviable. The result is a system optimized for low cost and high production and sales, not for repair.

Ignoring end-of-life design creates waste that someone else must clean up, and it weakens our economy by straining infrastructure, raising costs, damaging ecosystems, and exposing present and future generations to lasting health risks. In orbit, that waste circles the planet; on Earth, it piles up in landfills and scrapyards.

Shared space without shared rules creates shared problems. Space has become a shared landfill in orbit. Each country or company benefits from launching satellites, but the risks—collisions, equipment loss, and rising insurance costs—are borne collectively. It is often described as a “tragedy of the commons.” But that phrase is misleading. As Nobel laureate Elinor Ostrom showed, commons fail not because they are shared, but because they are ungoverned; left as open-access domains without rules or collective management.

Historically, the commons referred to shared resources—such as grazing lands, fisheries, and forests—that everyone could use. Some were managed sustainably through local rules and cooperation, but when no such governance existed, individuals acted rationally in their own interests, and the collective result was depletion. Orbital space today reflects this latter pattern: It functions as an ungoverned, open-access domain in which every launch consumes part of the shared resource of safe orbital paths. Maintaining collision-avoidance systems and insuring against debris risk already account for roughly 5–10 percent of mission costs, and are expected to rise as orbits become more crowded.

This open-access condition persists because global governance has not kept pace with orbital expansion. There are still no binding international rules requiring operators to remove defunct satellites or clean up orbital debris, beyond the broad obligations of responsibility and harm avoidance in the Outer Space Treaty (1967). The UN’s Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines (2010) remain voluntary and lack enforcement. Some national authorities, such as the US Federal Communications Commission and the UK Space Agency, now license commercial missions and require debris-mitigation plans for newly launched satellites. Yet these measures apply only within national jurisdictions, leaving global oversight fragmented and uneven. As private constellations expand at unprecedented speed—launching thousands of satellites each year—the governance gap has become a serious problem. What was once the domain of a few national agencies is now increasingly driven by commercial operators, accelerating congestion and multiplying the risk of collisions.

On Earth, the same pattern applies. Fragmented governance allows environmental costs to shift across borders. Producers and consumers benefit from cheap goods, while waste is exported to jurisdictions with weaker oversight and cheaper disposal, often poorer countries or fragile ecosystems. From e-waste to plastics and fast fashion, our fragmented environmental governance enables the same pattern: private gain, shared damage, and no effective global framework to ensure that polluters pay for the harm they cause.

A circular economy only works when rules are in place, and responsibilities are clearly defined and enforced. Otherwise, as in the tragedy of the commons, individually rational actions—launching satellites without end-of-life plans, designing short-lived products, or consuming goods under the assumption that someone else will handle their disposal—lead to collective harm: an orbit choked with junk above and a planet burdened with waste below.

Delaying solutions makes the problem exponentially harder. Earth’s orbit is not a single layer but a series of altitude bands with different decay times. In low Earth orbit (below about 600 kilometers), residual atmospheric drag gradually pulls satellites back down, allowing natural “clean-up” within years or decades. But higher orbits, such as those used for navigation and communications, lie beyond this drag. Objects there can persist for thousands, even millions, of years, effectively turning these regions into permanent dumps. Because each orbit serves a distinct purpose, congestion in them is, for all practical purposes, irreversible.

As launches accelerate, collision risks grow non-linearly: a single impact can generate thousands of fragments that trigger further collisions in a runaway cascade known as the Kessler Syndrome. Removing debris is technically feasible but prohibitively expensive, requiring a dedicated spacecraft to locate, match orbit with, capture, and deorbit each object. ESA’s planned ClearSpace-1 mission, scheduled for launch in 2026, will demonstrate the first active debris removal at a cost of about €86 million to capture a single 112-kilogram object. By comparison, launching an object of similar size costs well under €1 million, and such costs are expected to continue declining sharply as reusable launch systems, private competition, and economies of scale drive down the price per kilogram to orbit. Prevention remains far cheaper; even if cleanup technologies advance, debris will continue to grow faster than our ability to remove it because it accumulates exponentially, cleanup scales linearly and expensively, and governance lags far behind deployment.

Prevention means making circularity a requirement, not an afterthought. Every new satellite, public or private, should be licensed only with a credible and verifiable end-of-life plan to ensure controlled deorbiting within a few years after the mission ends. Regulators must make waste prevention a condition of launch approval, backed by enforceable standards and penalties for non-compliance. Yet prevention alone is not enough. Tens of thousands of legacy objects already orbit the planet, and removing them will demand costly, coordinated international efforts—from joint debris-removal missions to global funding and liability schemes grounded in the “polluter pays” principle. Without such dual action—designing out future waste while cooperatively addressing the past—orbital space risks becoming a permanently polluted commons.

We have already filled the Earth with rubbish, and we are now doing the same in space. The stakes are higher than they seem: orbit is already a critical part of Earth’s sustainability, yet it has become so crowded that a recent analysis of orbital traffic suggests a catastrophic collision could occur in days if collision-avoidance systems fail. Losing access to Earth’s orbit would undermine climate science, disaster response, agriculture, transportation, and the global coordination of communication and navigation networks. Without built-in pathways for recovery or safe disposal, waste accumulates by default, eventually choking the system. And someone always pays the price—whether through damaged ecosystems, disrupted services, or the loss of orbital access that modern life quietly depends on. The lesson is clear: If systems are not designed with circularity in mind, waste will build up by default, and the bill will eventually come due.

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today. Thank you!