“I cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag; I know that I am a black man in a white world.” — Jackie Robinson

Those immortal words were spoken 71 years ago, even as Jackie Robinson broke the color line in Major League Baseball, by throwing on the #42 jersey, and taking the field as a Brooklyn Dodger.

Lester Rodney, sports editor for the Daily Worker, predecessor of People’s World, wrote at the time:

“The cheers and commotion add to the pressure he’s under, sure, but he knew what he was doing when he started fighting for a big league job, when he became the first, the forerunner, knowing he had to be better than just good enough.

“The cheers may make it a little tougher on Robinson, the athlete, in a way. But the cheers are saying something, something that will make it easier for Negro players to come, for the day when there’ll be no special pressure upon an American ballplayer whose skin happens to be dark.”

Over the weekend, Major League Baseball honored Jackie’s memory by having all players wear the #42 on the field—a custom since 2009.

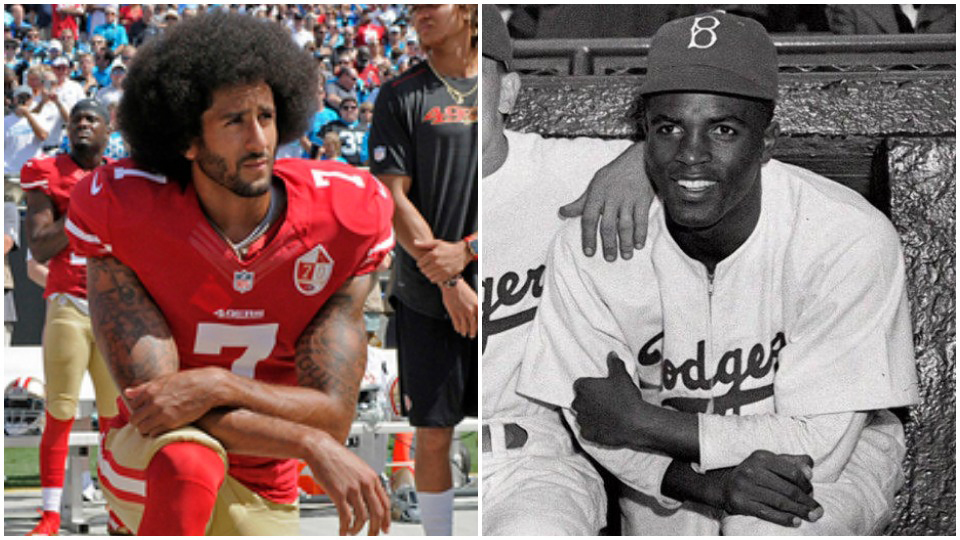

While baseball fans—including myself—celebrate the end of “color barriers” in professional baseball, we shouldn’t forget that even now, in 2018, we are still seeing the effects of “Jim Crow” professional sports. Just ask Colin Kaepernick, who continues to remain unsigned.

Unfortunately, those “cheers” Rodney wrote about have yet to make it easier for African-American athletes.

Kaepernick, who invoked Robinson’s quote Sunday, reminded us that the battle for racial equality in professional sports is far from over.

Kaepernick’s last game in the NFL was during the 2016 season with the San Francisco ’49ers. His actions on the sidelines, taking a knee during the national anthem to protest police brutality and racism, has led to his being “blackballed.”

Most recently, the Seattle Seahawks postponed talks with Kaepernick after he refused to assure the Seattle owners that he would stand for the national anthem this season. Also in the mixed bag of reasons why were his collision lawsuit and NFLPA grievance against the NFL and his other positions on social justice issues.

Though the workout had been scheduled weeks in advance, and the delay came right at the last minute, a team source said that it wasn’t connected to Kaepernick’s activism. I’ll let you draw your own conclusions, but personally, I think it was. Just look at the timing, especially with the Seahawks trading Michael Bennett and releasing Richard Sherman. Both were vocal supporters of the “take a knee” movement.

And if that wasn’t enough proof for you, then today’s re-signing of quarterback Austin Davis should be. Even if the Seahawks continue to say that the talks with Kaepernick are in a “holding pattern” and that bringing Davis back doesn’t rule out the possibility of signing the former ’49ers quarterback who led the team to their Super Bowl 47 appearance against the Baltimore Ravens.

But with the Seahawks’ back and forth positioning, it seems unlikely Kaeperinick will be making the move to Seattle.

Seventy-one years ago, the Daily Worker exposed the “Crimes of the Big Leagues.” Today, it’s the Crimes of the National Football League.

It’s no longer “Shame on MLB Commissioner Judge Landis.” Now it’s: Shame on NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell.

MOST POPULAR TODAY

High Court essentially bans demonstrations, freedom of assembly in Deep South

U.S. imperialism’s ‘ironclad’ support for Israel increases fascist danger at home

Resource wars rage in eastern Congo, but U.S. capitalism only sees investment opportunity

UN warns that Israel is still blocking humanitarian aid to Gaza

Comments