James Goldman’s The Lion in Winter is an actor’s actor piece of theater. The 1968 movie adaptation with stellar performances by Peter O’Toole as England’s King Henry II and Katharine Hepburn as Eleanor of Aquitaine left an indelible impression. The supporting (!) cast included Anthony Hopkins as Richard and future James Bond Timothy Dalton as King Philip. Lion received four Oscar nominations, and won two-Hepburn for Best Actress, and Goldman for Best Writing.

So with much anticipation I visited the newly refurbished Sierra Madre Playhouse to see the theatrical version of this medieval drama, which had premiered on Broadway in 1966. I was not disappointed.

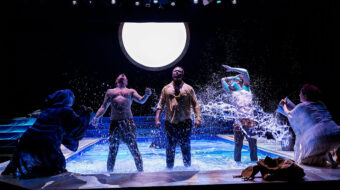

John Rafter Lee and Diane Hurley deliver bravura turns as the title character and his imprisoned, estranged wife Eleanor, whom Henry has permitted to leave her house arrest during the Christmas holidays of 1183. She joins Henry at the royal court in his castle in Chinon, France (the French-born British monarch presided over an empire), where their three sons are gathered as the 50-year-old grapples with the thorny issue of succession. The lads vie with one another to become heir to the throne: The eldest, Richard Lionheart (Adam Burch); the overlooked middle child Geoffrey (Clay Bunker); and teenaged John (James Weeks). Despite being the youngest and the least sharp rapier in the scabbards, John for some reason seems to be the affection-starved Henry’s favorite. (It never crosses their noggins that maybe the peasants should, like, vote on who shall lead them.)

Joining this big, if not so happy family are France’s King Philip (the Machiavellian Macleish Day) and Henry’s mistress, the French Princess Alais (Alison Lani), whom the conniving if convivial Henry hopes to marry off to one of his sons. Thrown into the mix, this makes for a most combustible concoction with more conspiracy theories than an Oliver Stone movie. Above all, the devious Eleanor and Henry match wits, as they eternally plot against one another.

It all plays out like a Eugene O’Neill drama set in the Middle Ages, although the relatives in question have vast powers and domains at their disposal. In addition to love between spouses, parents, children, and lovers, the temporal stakes are far greater than in O’Neill. But beneath it all are all too human frailties, not least of them the need to be loved, writ large on an imperial scale.

The play is funnier than the more dramatic film version, making for plenty of sparks a-flying and witty dialogue. Although after almost three hours (with one intermission), the verbal one-upmanship becomes somewhat tedious-not the fault of the acting, under Michael Cooper’s able direction. I think the problem lies with the type of characters portrayed.

During the Middle Ages European royalty reigned due to “divine right”: Those born of “noble blood” were pre-ordained by God to rule. But what Lion‘s action, characterizations, and dialogue reveal is that rather than being superior to the rest of us, monarchs are instead merely more bloodthirsty and avaricious. They may believe themselves our social betters because they are smarter than the 99 percent, but in reality they’re just more cunning than the masses because they’re motivated by greed and lust for power. Ever has it been so, down to our own Gilded Age of wild wealth disparity. So it does become tiresome to watch these “Type A” personalities compete for dominance, because truth be told, they’re just a pack of royal a-holes.

Albeit, as said, well-acted ones! On the theater’s new rake stage, sloped upwards away from us, the players seem truly larger than life. The period costumes designed by Carlos Brown delight the eye. If ticket buyers plunk down our buckeroos to see a period piece, most of us want the stage to act like a time machine and transport us long ago and far away.

Sammy Ross’s cleverly designed lighting imparts the sensation of flickering candlesticks, which is period appropriate. Gary Wissman’s set likewise helps us to willingly suspend disbelief, although the backdrop of a plain curtain becomes a bit dull.

This Lion roars, providing lovers of live performance with a rip-roaring night of thee-a-tuh that transforms the playhouse into a veritable lion’s den of drama amidst the jibes.

The Lion in Winter plays through Nov. 16 on Fridays and Saturdays at 8 p.m.; Sundays at 2:30 p.m. at the Sierra Madre Playhouse, 87 W. Sierra Madre Blvd., Sierra Madre, CA 91024. For more info: (626) 355-4318; www.sierramadreplayhouse.org.

Photo: John Rafter Lee and Diane Hurley of “The Lion in Winter” at Sierra Madre Playhouse. Gina Long.

Comments