For millions of workers, getting through the pandemic has been a major struggle for survival, while the largest corporations have enriched their wealth. The pandemic exposed the systemic, raw inequities in health, housing, and employment for Black and Latino families who suffered more losses.

These realities are shaping workers’ struggles emerging from COVID-19. One example is the epic battle for new union contracts and funding for the city now unfolding between the workers and the city standing up to Yale University.

Yale, one of the richest universities in the country, increased its endowment to $31 billion during the pandemic. Located in New Haven, a city whose population is majority Black and Latino, Yale’s huge tax-exempt landmass is a major contributor to the fact that the city is strapped economically. Yale’s hiring practices are a major contributor to the city’s official poverty rate of 26.5%.

The Black and Latino neighborhoods that historically have been red-lined are the same neighborhoods with the highest unemployment and the highest number of COVID-19 deaths.

“It’s time to change the map!” declared Tyisha Walker-Myers, president of the New Haven Board of Alders (city council) and chief steward of Local 35 Unite Here that represents service and maintenance workers at Yale most of whom are city residents.

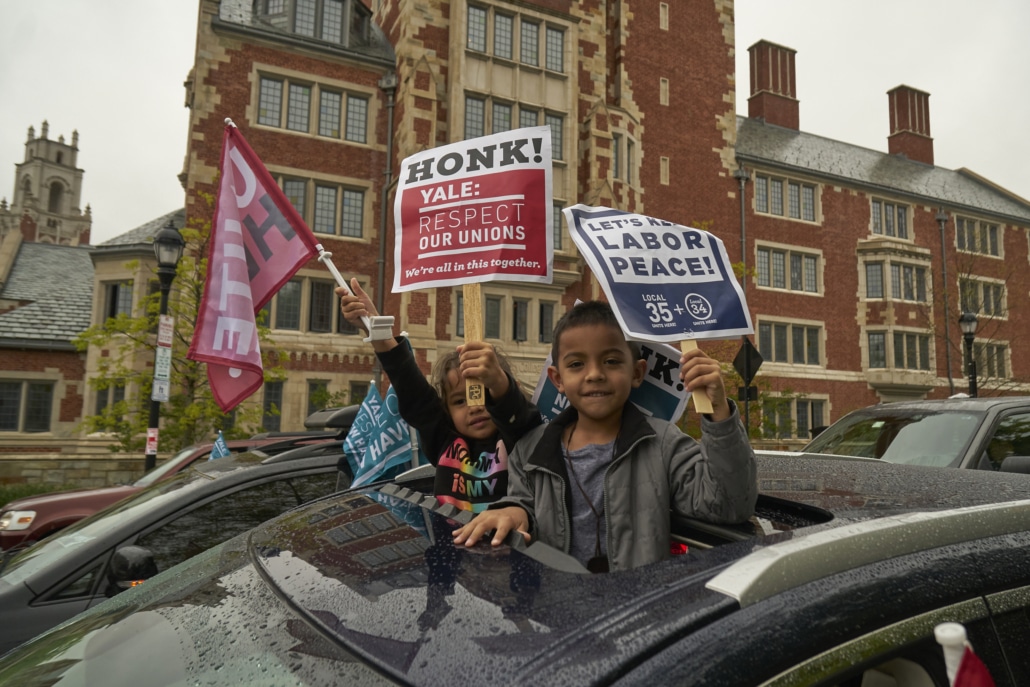

On May 5, well over a thousand workers, joined by the community, showed up in a massive 800 car caravan and march to demand “Yale: Respect New Haven.” The caravan jammed Prospect Street for several hours and then stopped traffic as it made its way downtown.

On May Day, union members and the community group New Haven Rising had painted the words “Yale: Respect New Haven” on the street at Prospect and Grove, contrasting the University’s small contribution to New Haven with the university’s $31 billion endowment.

“The turnout brought joy to my soul,” said Barbara Vereen, staff director of Local 34 Unite Here representing the clerical and technical workers; “We had so many members participating for the first time.” Together, Locals 34 and 35 represent over 5,000 workers at the university.

The action demands were for fair union contracts that maintain job security, good pay, and benefits; a substantial contribution to New Haven instead of taxes; fulfilling the promise to hire 500 workers from neighborhoods of need, and union recognition for graduate teachers Local 33.

A Local 34 member and newly-elected to the union’s Executive Board, Lynell Graham is an essential worker, assisting patients and families with their medical appointments. At the Connecticut People’s World May Day rally, she summed up the intersection of issues: “I work at the university, my children attend New Haven schools. Yale has pretty much said that they would outsource. We need these jobs to stay here.”

Graham continues, “I have not seen Yale give anything back. People come from all over the country to go to an ivy league school. And our own children, which are right around the corner, don’t have enough for lunches. Yale does not pay taxes in our city. And the amount, if they’d just pay taxes, would be such a big relief for us.”

Walker-Meyers also spoke at the May Day rally, saying, “There’s no reason why we have a world-renowned institution in our city and we have kids graduating from high school that have to take remedial courses in college. It’s unacceptable. We have kids that go hungry every single night — unacceptable!”

According to Walker-Meyers Local 35 members, considered “essential,” changed their lives and schedules during the pandemic. “We did everything to make Yale function. As soon as it was over, they wanted to come after our two largest departments, which are dining and custodial services. Which are mainly minorities and we all live in New Haven. Yale thinks we are afraid to lead our members out on strike. But we’re not. They might have money, but we have collective power and people.”

Outsourcing, sub-contracting, and job security have been among the biggest issues in contract negotiations for at least two decades. With community support, the Yale unions have mostly been successful in limiting their damage. But the Covid-related shutdown of most on-campus activity is accelerating Yale’s attempts to undermine the union workforce. There are reports from many departments that Yale will resume operations with a more centralized, automated, downsized, and outsourced staff, often cutting jobs by not replacing workers who leave or retire.

Ten years ago, Yale workers’ unions made a long-term commitment to the New Haven community. Going door to door, volunteers talked to ordinary residents in all the neighborhoods about their priorities and a grass-roots community organization, New Haven Rising, was built. The new organization registered thousands of voters, and union members and allies were elected as a majority of the 30-member Board of Alders.

The fruits of this alliance came in 2015-2016, when community members joined Yale workers in a successful campaign to save 986 union jobs at the Yale medical school that were threatened with outsourcing. At the same time, community pressure led to an agreement by Yale to hire 1,000 New Haven residents — including 500 from “neighborhoods of need” over 5 years. Again in 2019, at a hearing called by the Board of Alders’ Black and Hispanic Caucus, hundreds of residents spoke out to demand that Yale fulfill and extend its hiring agreement.

New Haven Rising organized hundreds of residents to attend this year’s city budget hearings, calling on Yale to increase its contributions. New Haven is almost entirely dependent on property taxes for revenue, but more than half of all real estate is tax-exempt, with Yale accounting for the biggest chunk. As a result, services are limited, and property taxes on homeowners and businesses are high. If Yale paid taxes on all of its property, it would mean an extra $157 million in annual revenue — equivalent to 26% of the city’s budget.

Last week, the alders adopted a budget that includes a $4 million increase in Yale’s contribution, adding to the university’s pressure to deliver. The city budget also includes an increase of $49 million in state funds, dependent on the final state budget to be decided in the next week. Yale unions and New haven Rising are part of the statewide Recovery for All coalition, fighting for better state funding for services and cities. It would be financed by taxes on Connecticut’s millionaires, who now face a much lower burden from state and local taxes than working-class residents.

Seventy members of the unions at Yale and New Haven Rising were part of Unite Here’s groundbreaking door-to-door efforts in the midst of the pandemic, helping mobilize votes in Philadelphia to carry Pennsylvania for Biden-Harris. In December, they traveled to Georgia to help to secure the breakthrough victory that enabled Republican obstruction in the Senate to be partially overcome.

The victories in these elections are strengthening the fight for worker’s rights as the pandemic recedes. Participants in these campaigns have been given a new sense of their power. Going into contract negotiations, they have experience and determination. Local 34 Executive Board member Mary Thigpen said, “Of course our election work can help get a contract. Now, with Biden, people have the right to organize. That will be power. This is important not just for unions but for communities.” She concluded, “We will end up with another good contract.”

In their unions and their communities, working people across the country are fighting for something better than a return to a “normal” of growing inequality. Their struggles are demanding a larger share of the wealth produced by the working class, a voice at work and in government, and dismantling the structures that perpetuate racism and inequality.

In this environment, the organizing in New Haven around Yale University is a national example: the unity of the three Yale unions, representing clerical and technical, service and maintenance, and graduate teachers; the long-standing ties to community struggles for jobs and public resources; the merging of union and political organizing leading to coordinated power in the workplace and at City Hall; and uniting around the demand to “change the map” of racism, which for almost a century has concentrated poverty, unemployment, crime, and now COVID in the same neighborhoods, occupied primarily by people of color.