LOS ANGELES — Mauricio Terrazas, a longtime Mexican American activist and trade unionist, died here recently at the age of 92.

Terrazas was born Jan. 28, 1917, in El Paso, Texas. His father, also named Mauricio, and his mother, Josefa, had 16 children, eight of whom survived including Mauricio. Juana, Emilia, Berta (this writer’s aunt: she married my uncle Emilio), Aurora, Carolina, Guillermo and Carlos.

In 1937, at age 20, Mauricio rode a freight train to Los Angeles, where he worked in the downtown produce market, for the Southern Pacific Railroad, maintaining and laying tracks, in a laundry and other places. In 1939 he brought his family to Los Angeles.

At the height of the Depression, the speakers at the street corners who discussed the devastation of working people impressed Mauricio. He joined the Communist Party because he saw that they had an answer to the poverty and suffering he saw around him. He helped the party organize workers, which exposed him to other organizations helping the under-served.

In 1945, Mauricio became a truck driver at Safeway stores, where he worked for 20 years. In 1946, he married Irene Malagon, with whom he had four children: Eddie, Linda, Orlando, and Conrado.

Mauricio and Irene were community activists. He wanted to become involved in the Community Service Organization, but they did not want members of the Communist Party. He volunteered for Edward Roybal’s successful campaign to win a Los Angeles City Council seat in 1949. He also was involved in the Committee to Defend the Foreign Born in the Los Angeles area. Around 1954, he helped found the Mexican American Political Association. During the 1950s the FBI followed him to his home and work, and Irene was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee. The Mexican American community struggles suffered greatly as a result of the McCarthy period. But the witch-hunters were unable to deter Mauricio.

In 1965, in the first Christmas for the United Farm Workers union grape boycott, he convinced Safeway Stores to donate a truck and he drove it to Delano filled with food and toys. Safeway stopped supporting these efforts when they became the target of the UFW boycott.

In the 1970s, Mauricio became involved with Teamsters for a Democratic Union to make his union more democratic.

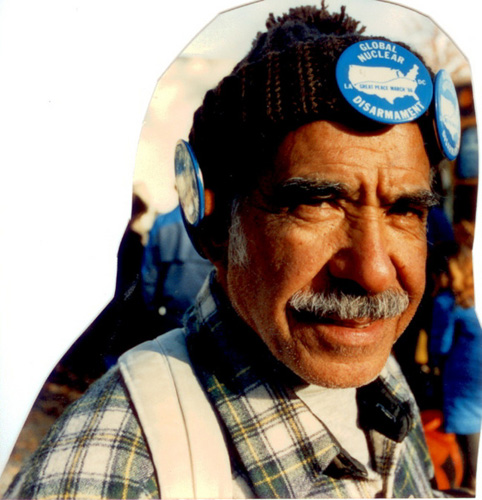

In 1986, Mauricio joined the Great Peace March for global nuclear disarmament. It began in Los Angeles and traveled for nine months to Washington D.C. Thousands of people joined the march. He met his second wife Jean at that march; they married soon after.

Mauricio spent the last 23 years in happiness with Jean. They continued their activism by opposing the war in Iraq. Mauricio was a reader of the People’s Weekly World until his death on July 8.

Each of his children spoke of their father’s devotion to make this a better world. They told stories of their father’s activism. Mauricio’s daughter said she remembers when her father would get them up to go to a demonstration, telling them that people fought for the eight-hour day and other things they now enjoy and that it was their responsibility to give back to the community.

His son Orlando described how, when his father arrived in Washington, he went straight up to the desk at the most expensive hotel and told the manager that he had just walked 3,000 miles for the manager and his family and he would like a room to rest in for free. The manager gave him a suite and did not charge him a dime.

Mauricio’s other son, Conrado, said that when he became an open gay man his father embraced him with open arms, saying “You are my son and I love you.”

Comments