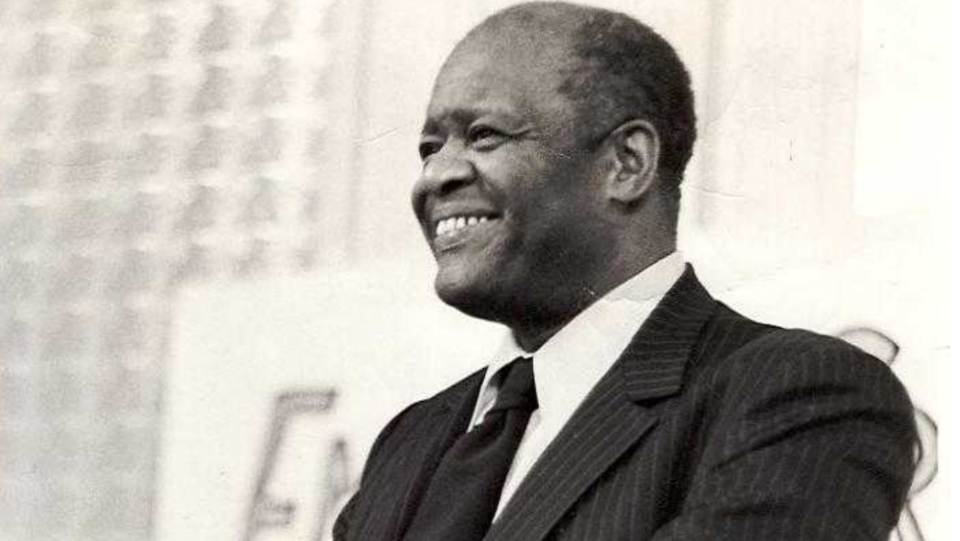

The following article originally appeared in Political Affairs in 2012. It is based on remarks delivered by the late Charlene Mitchell at an event commemorating the 100th anniversary of the birth of Henry Winston, a leader of the Communist and Black Liberation movements who died in 1986. Charlene Mitchell was a long-time labor and political activist; the first Black woman candidate for President of the United States, running for the CPUSA in 1968; and a founder of the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism.

I count myself as among the lucky ones who had the privilege of working with Henry Winston over a number of years and in a number of struggles. Karl Marx wrote that: “Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.” Henry Winston made history, but his contribution to history was not based on his unique genius, although he was a genius. The history he made was grounded in the world he lived in.

Growing up in Hattiesburg, Miss., and Kansas City, he experienced first-hand the brutal oppression of the African American people and the callous exploitation of the working class. In Hattiesburg, in the early 1900s, more than one-half of the town was African American, yet only one percent of them were registered to vote due to the disenfranchisement of the African American people in the South.

His father was a laborer in a local sawmill, who struggled to feed, clothe, and house his young family on the meager wages of the mill. Thus, from birth, Winston’s life was intertwined with the two social forces that would mark his future life—he was a member of the working class, viciously exploited by the capitalist system, and he was an African American, subjected to the base degradations of national oppression.

As a fighter, Winston grew to adulthood organizing against these twin forms of oppression. He was a leader of the Young Communist League, the Unemployed Councils, and the

Scottsboro Defense Committee. In the midst of these struggles, he honed the theoretical and organizational abilities that would serve him so well later as a leading member of the Communist Party USA.

Many of Winston’s most lasting theoretical contributions are in the areas of the anti-colonial and independence struggles of Africa and the movement for African American equality. Although his personal life experiences certainly gave him important insights into these issues, it was not a sense of nationalism that drove his analysis. Instead, it was a firm belief in the future of socialism and the historic role of the working class in bringing about that future. Winston was fully aware of Lenin’s admonition that Marxism cannot be mixed with even the most refined forms of nationalism.

In a 1964 pamphlet entitled Negro Liberation: A Goal for All Americans, Winston referred to the African American question as “the touchstone in the struggle for democracy in this country,” adding that “the achievement of equality for the Negro people is the key in the struggle to defend and extend democracy for all.”

Winston was an advocate of the centrality of the struggle for African American equality. He understood that the fight against African American oppression was “central” to the unity of the working class. He understood that this “centrality” could not be posed against the class struggle—as some social democrats attempted to do by insisting that only

the class struggle is “central.”

Instead, Winston understood the interconnection between the class struggle and the struggle against national oppression. He also understood that no movement would lead the U.S. working class toward the fundamental transformation of this system without a correct understanding of the centrality of the fight against African American oppression. The white sector of the U.S. working class will never break with bourgeois ideology without cleansing itself of the odious ideology of racial superiority—in whatever form it takes.

These ideas, the struggle for a correct line in the African American and African support movement, are the centerpiece of Winston’s book, Strategy for a Black Agenda. In that work, which was a major intervention in the ideological struggle within the African American movement and among those in solidarity with African liberation and independence, Winston pulled the covers off of the Maoists, who under the guise of “anti-revisionism” sided with the imperialists in the struggle for the liberation of Angola.

More importantly, Winston’s analysis demonstrated that these positions were not merely mistakes or errors in judgment by the Maoists, but were the logical outcome of an anti-Leninist, anti-working class philosophy.

In that book and in his Class, Race, and Black Liberation, Winston also dissected the then-current Pan-Africanist movement. He demonstrated that the nationalism and lack of anti-imperialist grounding in that movement reflected that it owed more of an intellectual debt to George Padmore and Marcus Garvey than to DuBois’ conception of Pan-Africanism.

He noted that they were quick to base their analysis on Dubois’ famous quote that “the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line.” However, Winston added, “Dubois said it was the problem, Dubois did not say it was the solution.” Winston went on to write, “As Lenin demonstrated, the solution lies in a strategy to overcome the disunity of the oppressed and exploited at the line of differences in color and nationality.”

Comrade Winston’s leadership on these issues was not limited to the theoretical sphere. He played an active role in guiding mass movements in these areas. Winston was the organizational brains behind the formation of NAIMSAL, the National Anti-Imperialist Movement in Solidarity with African Liberation.

Under his guidance, and through his connections with African leaders throughout the continent, NAIMSAL succeeded in injecting a consistent anti-imperialist content into the then-developing movements in solidarity with African liberation. NAIMSAL was one of the first organizations in this country to campaign for the freedom of Nelson Mandela and, with the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression (NAARPR), launched a petition drive that helped make Mandela’s freedom a national issue.

Much of NAIMSAL’s work laid the basis for the larger African liberation support movement that

developed in the 1980s.

And under Winston’s guidance, the Communist Party helped build the largest political defense movement this country had seen since the Scottsboro defendants of the ’30s. I can still remember receiving a call from my brother, Franklin Alexander, in the summer of 1970 informing me that Angela Davis was facing arrest on trumped-up charges stemming from a shootout at a courthouse in San Rafael, Calif.

I immediately went to discuss this development with Winston and Gus Hall. Both had no hesitation in throwing the weight of the entire party behind the movement to defend Angela, and both immediately saw this threat as an attack against the Communist Party, the African American movement, and the entire progressive movement.

Winston, especially, demonstrated a particular sensitivity to the role of gender. It was an advanced attitude I had seen displayed by him over the years. In his work in defense of Angela, he consistently expressed the importance of the role of women in the movement’s leadership and in the broader society. This may have partially been due to the influence of Claudia Jones, one of his closest comrades from the “old days” and at one time chair of the Communist Party’s Women’s Commission.

With Winston’s assistance, we rallied the Communist Party to build an international movement demanding the release of Angela and all political prisoners. This movement, more than any other single motion, helped rebuild the CPUSA’s image in the African American community and in the broad left. There are still many activists around who “cut their political teeth” in that movement. And in the process of building that movement, the party made many valuable contacts with activists across the country. It was this movement that positioned us to launch the NAARPR.

In Winston’s last years, he had developed a particular concern for the plight of African American youth. He recognized that the general crisis of capitalism and the national oppression of the African American people were combining to stigmatize African American youth as, in Winston’s words, “social pariahs.” Decades later, we see Winston’s concerns manifested in astronomical youth unemployment rates, collapsing public education, and mass incarceration as a method of control of African American youth.

Yet Winston was full of optimism about the long-range future.

In a 1951 pamphlet, entitled What It Means to be a Communist, Winston wrote: “Those who see only backwardness, immobility, and disunity in the working class, are bound to ignore the essential truth that it is the working class that possesses all the necessary qualities to bring about the transformation of society, and build socialism.” The working class and its allies are the only force that can bring about the fundamental transformation of this society.

It’s important that we honor the life and legacy of Henry Winston. But we must also recognize that Henry Winston was not a great man in spite of being a Marxist-Leninist. He became a great man because he was a Marxist-Leninist. He was not a great man in spite of being a member of the Communist Party. He became a great man because he was a member of the Communist Party.

Nothing in his contributions makes sense if separated from the Communist Party and its ideology. And yet, his legacy belongs not just to the Marxist-Leninists or to the Communist Party.

His legacy belongs to the African American people, to the working class, and to the oppressed people all across this world, who all strive for a better society and a better future.

People’s World has an enormous challenge ahead of it—to raise $200,000 from readers and supporters in 2023, including $125,000 during the Fund Drive, which runs from Feb. 1 to May 1.

Please donate to help People’s World reach our $200,000 goal. We appreciate whatever you can donate: $5, $10, $25, $50, $100, or more.