As the country continues to be divided on politics and “culture wars,” one American institution has been thrust into the center of it all—libraries. While heated debates surrounding book bans and attacks on education have been making headlines, a new documentary presents a compelling case that the American public library has always been at the heart of democracy.

Free for All: The Public Library uses the power of history to shed light on how essential public libraries are, and why the attacks on their ability to provide books and services to the community dismantle progressive change.

Directors and producers Dawn Logsdon and Lucie Faulknor (Faubourg Treme: The Untold Story of Black New Orleans) chronicle the evolution of the American public library’s trajectory. The documentary takes viewers on a journey from the original “Free Library Movement” that began in the late 19th century to the present, when many libraries find themselves caught in the crosshairs of the culture wars as they struggle to survive amid budget cuts and closures.

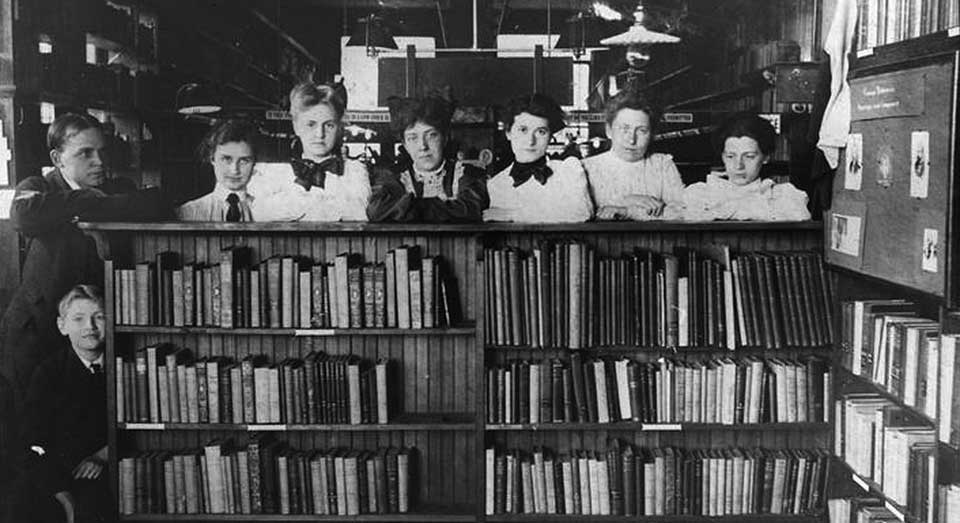

The film interweaves personal tales with expert opinions, archival footage, and recent news stories to paint a layered picture of the influential place public libraries hold in our society. It is through history that the doc showcases that the library has never been a passive institution bending in whichever direction that those in power push it towards, but rather a place on the forefront of change and progress, with numerous influential figures—often women—who helped to spur the communities they served as librarians forward.

The result is an educational and stirring 90 minutes of under-taught American history that gives nuance to the current far-right conservative pile-on to defund libraries because of the role they serve in working-class communities.

Free for All makes it clear that the origin of the American public library is a rebellious one. It explains that for most of human history, libraries weren’t accessible to ordinary people.

Reading and education were something reserved for the so-called wealthy elite and nobility. There was even a time when the Catholic Church discouraged devotees from reading the Bible themselves or translating it into their native languages. Martin Luther’s translation of the bible into German, his country’s vernacular, set off widespread religious warfare and the end of a unified Roman Catholic Church in Western Europe with the birth of Protestantism.

Highlighting Benjamin Franklin, historians explain that although he’s plastered on the U.S. 100-dollar bill and associated with capitalist wealth, his greatest legacy is the public works he helped to establish—the public library being one of them.

As the Revolutionary War of 1776 drew near, Franklin reflected on the power of the initial lending library system he helped to create in fostering the belief that people needed to be educated to govern themselves. He’s quoted as saying that “these libraries have improved the general conversation of the Americans” and “made the common tradesmen and farmers as intelligent as most gentlemen from other countries.”

The Boston Public Library, established in 1848, would follow this ideal as a pioneer of public library service in America. It would become the first large free municipal library in the United States, and the first public library to lend books.

It is through these tidbits that viewers are made to understand that the public library’s history is American history, and its evolution is reflective of the evolution of the United States. This is made very clear in one of the major themes the film focuses on: the role of women librarians.

This section of the film is perhaps its most compelling as it gives detailed information about important women trailblazers lost to history. It provides an image of librarians not often explored in mainstream media.

They are shown to be community advocates, social activists, and curators of empowerment through knowledge. This is because many women were empowered through becoming librarians.

In the early days, women librarians were required to be single, and this afforded them the opportunity to earn an income without the pressures of marriage and bearing children. Free for All goes into the fascinating details of how this came to be, and how the spreading of public libraries across the country was intertwined with the feminist movement and women’s liberation.

This kind of liberation and freedom was happening during a time when it was believed that if women read too much, they could become infertile. And that fictional stories could cause inflammation of the female heart.

Viewers will learn about important women such as Gratia Countryman, who led the Minneapolis Public Library from 1904 to 1936. Mary Ann Shaw, a Black woman who was an educator and philanthropist who helped fund Flushing Free Library, which later became part of the Queens Library organization in New York. Sarah Smith, who was an Indigenous woman who founded the first library for Native American children.

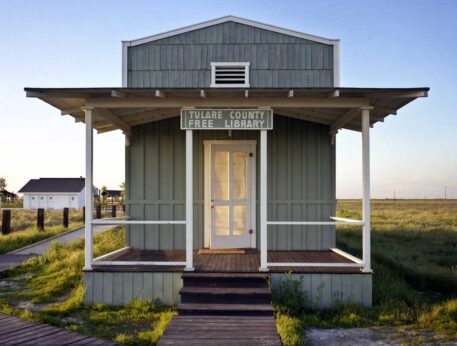

A significant portion of the film focuses on Lutie Stearns, a librarian, author, and political activist who traveled throughout the country with her mobile library to provide books to underserved communities in the rural areas of America.

The documentary also gives attention to the role that libraries played in the fight for racial equality and Black empowerment. While many have most likely heard about the Harlem Renaissance of the 1930s, the Harlem Library Movement is lesser known, yet just as impactful. Black librarians encouraged artists to create in the library space, which became a central hub for playwrights, poets, actors, and painters. Free for All shares stories of how libraries helped to influence many great Black leaders and thinkers in American history, such as James Baldwin and Martin Luther King Jr.

The film focuses on the multiracial effort to desegregate libraries during the time of Jim Crow, once again showcasing the way in which libraries have been at the forefront of social change.

Free for All provides much of this historical foundation to ultimately address the socio-political elephant in the room. That is the current far-right conservative attacks on the public library and the services and books it provides to communities. The film makes clear that censorship is not something new to public libraries.

From the early onset of this institution, there have been books that it provided that pushed back against the status quo. Images of the covers of Frederick Douglass’s My Freedom, The Woman’s Rights Almanac for 1858, Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman, and Manifesto of the Communist Party by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels are shown on screen in the film to drive home this notion.

The doc notes that during the McCarthy era of red-baiting and anti-communism, librarians like Ruth Brown, who fought for racially integrating the public library, were black-listed and accused of being un-American. Comparisons are made between the book burnings in 1930s Nazi Germany and the book burnings that have recently taken place in the United States.

The film argues that the “tax revolt” that began in California in 1978 through Proposition 13, and caused a chain reaction across the country of limiting government spending that ultimately saw libraries getting the brunt of the budget cuts, continues to significantly impact public libraries. Other, more recent happenings, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, natural disasters, and political divisions, have put libraries in the spotlight in a time when many are battling to keep their doors open.

In understanding the role that public libraries play for working-class communities, such as providing high-speed internet access (something 24 million Americans still lack in their homes), access to reading materials to expand their minds, a warm or cool place to sit depending on the weather (especially for the homeless), and workshops to help the community they serve, it is no wonder that there are regressive forces at work who seek to dismantle such an institution.

The powerful aspect of Free for All is that it doesn’t explicitly say this, but lets history speak for itself. By providing a thorough and captivating journey through the years, we, as viewers, are made to understand that the existence of the public library speaks to the idea of the empowerment of the people.

It has long stood as a beacon of hope for many marginalized groups, such as women, Black people, immigrants, and other communities of color. It currently stands as a free source of support in a time when social safety nets that working people fought for are being gutted and threatened. The word democracy comes from the Greek words “demos,” meaning people, and “kratos,” meaning power. Thus, democracy can be seen as “power of the people”—something in which the public libraries wholly exemplify.

To learn a significant aspect of American history that is not often explored in the mainstream, Free for All is a must-watch. It is essential to understand why libraries have become the battleground in the culture wars, and it’s a necessity for those who value freedom of thought and democracy to defend their continued existence.

Free For All: The Public Library will debut on PBS’s Independent Lens on Tuesday, April 29, 2025, at 10 p.m. (check local listings.) The film will be available to stream on the PBS app.