LOS ANGELES—If the name of photographer Baron Wilhelm von Gloeden means anything to you, you’ll know immediately what I’m going to be writing about here.

Von Gloeden (1856-1931), a German ex-pat who set up a photography studio in Taormina, Sicily, in 1897, was a prominent figure in the late 19th-century movement to validate homosexual love in a world (see: the trial of Oscar Wilde) that not only did not understand it but in many countries severely punished it. The intellectual guiding lights of that early homophile movement were inspired by tales of ancient Greek love, documented in myth, legend, military lore, and in philosophical treatises such as Plato’s Symposium. The traditional model of homosexual love involved the mentorship of a younger man by an older man who would aid his youthful partner in learning life’s lessons. Some of these relationships turned into enduring commitments, while others formed part of a young man’s education, as either partner was also free to marry and sire children according to the standard practice of their times.

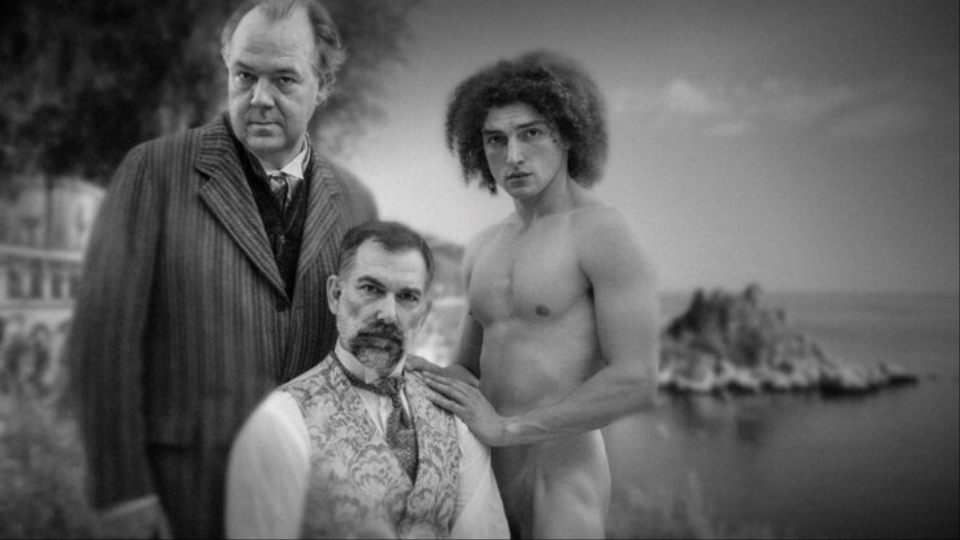

As a photographer, von Gloeden was drawn to recreate imagery from ancient times with the boys (and girls) he hired from the local community to pose as nymphs, fauns, peasants, and historical figures depicted in classical sculpture, with appropriate loincloths, sandals, turbans, wreaths, garlands, pottery jars and flora as part of the makeup and décor against background settings such as Mt. Etna and ancient ruins.

Today, many of these images seem quaint and fey (search his name on Wikimedia Commons for a generous selection of images), but in their day they represented the highest form of queer art in photography. Only some showed the male completely nude, and fewer of these any genitalia, but foreign visitors to von Gloeden’s studio, from repressive America and Northern Europe, found them sublimely liberating, beautifully capturing the essence of pure and generous selfless love. Painters of the time, such as the American Maxfield Parrish (1870-1966), similarly exploited such neoclassical themes with androgynous figures from an imagined fantasy world.

In Tom Jacobson’s world premiere production of Tasty Little Rabbit, the playwright explores the context of von Gloeden’s studio in its heyday, as well as the repercussions of his art 30 years later, once Mussolini’s fascists have come to power. The through-line between the two eras is provided by one of his models, Pancrazio Buciuni, whom we meet as the “tasty little” 18-year-old” of the title and see later (more fully dressed and wearing a hat) as a 57-year-old, married with five children, preciously guarding the studio and all its negatives and prints that the photographer left him upon his death.

In the earlier period, we meet the photographer, played by Robert Mammana, who in the alternating later scenes also plays an officious minor local fascist, Cesare Acrosso, assigned to the job of erasing these “degenerate” unmanly images from Italy. A third actor, Rob Nagle, plays the Irish-British poet Sebastian Melmoth who visits the studio, and later one Francesco Maffiotti, sent out from Rome to oversee the case, though he is more tolerant and open-minded and discourages overly punitive measures for what he acknowledges is in the end, not pornography but simply art.

A final “character” in the play is the Sicilian character itself and the culture of “umirtà” (a variant of the word “omertà”), a code of silence and loyalty, best known today as the modus operandi of the Mafia, which never cooperates with authorities or outsiders. This code comes into play when it becomes clear that only three decades or so later, many of the boys and girls von Gloeden photographed, and with whom he remained friendly until his death only a few years earlier, in 1931, were still very much around and deeply proud of their artistic immortalization by the world-renowned artist who lived peaceably among them. Sicily was considered the last fascist region of Italy.

A final “character” in the play is the Sicilian character itself and the culture of “umirtà” (a variant of the word “omertà”), a code of silence and loyalty, best known today as the modus operandi of the Mafia, which never cooperates with authorities or outsiders. This code comes into play when it becomes clear that only three decades or so later, many of the boys and girls von Gloeden photographed, and with whom he remained friendly until his death only a few years earlier, in 1931, were still very much around and deeply proud of their artistic immortalization by the world-renowned artist who lived peaceably among them. Sicily was considered the last fascist region of Italy.

I don’t think it’s too much of a spoiler to reveal that the visiting Irish-British poet turns out to be none other than Oscar Wilde, still profoundly traumatized by his experience as a convict in Reading Gaol (1895-97) in the homosexual scandal that rocked late Victorian England and prodded British homophiles to seek their pleasures abroad. Wilde would die at age 46 in 1900, a broken victim of homophobia.

Ironically, the fascist movements—and we still see this today—had their own version of uplifting male culture and physique in ways that social theorists also identify as somewhat homoerotic. Politicians such as JD Vance and Missouri’s Senator Josh Hawley put down women and queer folk of all stripes in their scheme to promote straight white male superiority.

Tom Jacobson bases much of his dramatic output on historical events. I have had the opportunity and pleasure of assessing a number of his earlier works, such as, recently, The Bauhaus Project and Crevasse, and in the past, Tar, Plunge, and Mexican Day. He has a congenial and stageworthy manner of folding his historical characters into his plays in ways that look and sound natural, both contemporary to their times and still relevant today.

He continues in that same spirit with Tasty Little Rabbit, reminding us that queer liberation did not start with the Stonewall Rebellion of 1969, but had its antecedents at least a couple of generations before, and indeed, it would not be hard to argue, several millennia back in time, in the era von Gloeden’s imagery evokes.

Recalling his discoveries about these confiscated photographs and Buciuni’s latter-day ownership, Jacobson asks, “What were his feelings about these renowned images of himself that the government declared obscene? What was his relationship with von Gloeden? Our feelings about von Gloeden’s work today are complicated, and understanding Buciuni helps us approach these extraordinary and groundbreaking images more honestly and with greater empathy. Theatre and photography—especially portrait photography—are grounded in empathy, so theatre is a wonderful way to tell this photographic story. The play reveals a number of secrets that make it both fun and dangerous.”

Director George Bamber says, “Benito Mussolini used moral cleansing as a means to gain control of the people in Italy. Tasty Little Rabbit focuses on one such persecution of 1890s photographer Baron Wilhelm von Gloeden. He was the Gilded Age’s ultimate ‘influencer.’ His photographs of the locals on the Sicilian coast made the village of Taormina a required stop on the grand tour, particularly for prominent men attracted to beautiful male youth. What drew me to the play, what made it essential for me to direct, is Tom’s unparalleled ability to make issues of complexity more understandable. We are too easily manipulated by headlines that force us to stand either on the right or the left. Tom’s skill is holding our focus so we can contemplate the complexity of art vs pornography, normative vs deviant orientation, sexual agency vs exploitation.”

This play is a part of “Reflections on Art and Democracy,” a celebration of plays and lectures in Los Angeles aimed at raising awareness about the rise of fascism, racism, and antisemitism, the power of art and design to resist them, and the confluence of visual and performative artworks to promote democracy.

I recommend this play wholeheartedly, especially if, like me, you are interested in the subject matter. (I’d go so far as to say that anything Tom Jacobson turns his mind to would almost certainly be of interest to me). Discussing the play as we left the theater on opening night (May 2), my companion and I did question the viability of reducing the cast to three performers impersonating six roles. I understand the economics of it, but does it work? One can always use suspension of disbelief to accept a single actor as a young man of 18 and as the same person in his 50s with a hat. But with the other two actors, the parts they play are so unrelated that I wonder if, in its next iteration, sometime somewhere, a director might choose to cast a couple more actors.

Tasty Little Rabbit runs 90 minutes without intermission, playing through June 6 with performances Fri. and Sat. at 8 p.m. and Sun. at 4 p.m. There is one additional performance Thurs., June 5 at 8 p.m. Moving Arts is located at 3191 Casitas Ave., Los Angeles 90039, with plenty of parking in the building’s lot. Ticket information and reservations can be found here. And yes, for the easily shocked (or titillated), there is one brief scene featuring frontal male nudity.

Mark Mendelson is responsible for the atmospheric scenic design, and Garry Lennon is responsible for the costume design. Lighting is by Dan Weingarten, and sound design by John Zalewski. Projections are by Nicholas Santiago.