East Germany’s Minister for Education, its First Lady Margot Honecker, assessed the post-war beginnings of the young German Democratic Republic (the GDR, or East Germany) writing in her memoir, “Antifascists, communists, socialists, people of different worldviews, who came from their imprisonment in concentration camps, prisoners of war in different countries, the republican partisans who fought in the Soviet Union and with the Resistance—now they were together with democratic enemies of Hitler, to erect an anti-fascist, democratic order. They were supported in the Eastern zone (of postwar Germany) by the authorities of Soviet occupation.

“Starting a democracy demanded the mobilization of the capacities of all the layers of the people. The key condition was to build the unity of the working class…. Without the union of all these patriotic forces into the National Front the mobilization of men and women for a new democratic beginning, to impose basic democratic reforms in the economy and the state, and, therefore, the construction of socialism, would not have been possible.” (The Other Germany, The GDR).

Recalling Honecker’s writing about the latter part of the 1940s-50s provokes surreal, disjointed, and out-of-body feelings when attempting to reconcile this posture against an objective assessment of the United States during the same period.

While the “antifascists, communists, socialists” of the GDR were departing as rigorously as they could from the stench of two disastrous wars and an ethnic genocide, the elites of the United States were busy trying to return to the 19th century and preserve Counter-Reconstruction and Jim Crow.

Remind me again who was the “Greatest Generation” of a “Golden Age?”

A story, which may be apocryphal, related by historian Stephen Ambrose, nevertheless highlights the duplicity of the U.S. position. Ambrose states and historian Taylor Branch repeats, how amid the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v Board of Education case, our war hero-turned president Dwight D. Eisenhower pondered out loud to Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren if he wanted little white girls to be “sitting next to n*****s” in public schools (another version has Eisenhower saying “big Black bucks” instead of the racist epithet). This might reveal why the president dragged his feet so long to federalize National Guard troops to integrate a few Black students into an Arkansas high school. The national flower of the United States is the white woman.

At the same time, without a shred of irony, this same beacon of democracy and relatively minor player in that last war, was using its diplomatic, military, and spy resources to ensure that the most retrograde, authoritarian capitalist regimes filled that area declared under Monroe’s Doctrine to be a vast sphere of the United States.

Could this be the same world Mrs. Honecker was describing?

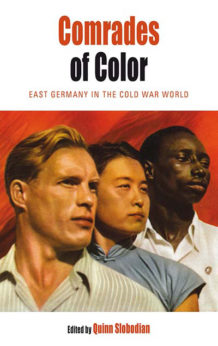

Quinn Slobodian is an associate professor of history at Wellesley College, but it seems to have taken a few years and a story of its own for his 2015 anthology to be published in the United States. I imagine Comrades of Color: East Germany in the Cold War World has too many strikes against it to make the New York Times Bestseller List. It is history. The anthology balances fairly the goals and conundrums of an avowedly anti-fascist, socialist workers’ state. It treats the global South in general and Africa in particular without any duplicity or reservation, unlike our war-hero, anti-Black president.

Quinn Slobodian is an associate professor of history at Wellesley College, but it seems to have taken a few years and a story of its own for his 2015 anthology to be published in the United States. I imagine Comrades of Color: East Germany in the Cold War World has too many strikes against it to make the New York Times Bestseller List. It is history. The anthology balances fairly the goals and conundrums of an avowedly anti-fascist, socialist workers’ state. It treats the global South in general and Africa in particular without any duplicity or reservation, unlike our war-hero, anti-Black president.

To a gun-toting, obsessively Black-fearful country that imagines the “good old days” to be those very days when this country was conniving to maintain its apartheid system, a book like Comrades of Color will find a small audience here in the U.S. Hence, it was published in the UK initially.

What Comrades of Color offers is a glimpse of what an aspiring socialist workers’ state, with internationalist values, struggled with from the beginning and right up to its demise.

Struggle, in this sense of the word, is not to evoke those beautiful partisan art-deco posters from anti-Franco Spain or Soviet war imagery. The struggle within the GDR was spiritual and of the kind where “people of different worldviews,” “to impose basic democratic reforms in the economy and the state,” seeking a common goal must look inward and develop as they go forward.

Inevitably, Slobodian writes, “the GDR’s commitment to otherwise abstract notions like solidarity and shared struggle against imperialism” brought successes, like East Germany’s assistance in rebuilding post-Vietnam War Ho Chi Minh City, but it also had some unforeseen consequences.

Two cases best illustrate the complexities of the GDR’s internationalist struggles.

East meets Africa

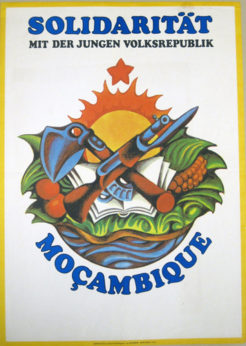

In the spirit of the USSR’s Patrice Lumumba University and Cuba’s Latin American School of Medicine, the GDR inaugurated the Schule der Freundschaft (School of Friendship) in 1981, even though its monetary commitments to the global South—scant in comparison to the better-financed West Germany—began as early as the 1950s.

Contributor Jason Verber’s piece on the GDR, Mozambique’s Liberation Front (FRELIMO), and the founding of the School of Friendship reveals the practical problems faced when the GDR’s “ideas of socialism” conflicted with the “politics of FRELIMO,” both of which often collided with the actual realities of a developing socialist state during the Cold War.

There is a subtext here and throughout the book, of opposing cultures, “people of different worldviews”—the GDR and Mozambique; the GDR and the DPRK (North Korea); the GDR and socialist Vietnam; the GDR and Cuba—that this was an internationalist project, and the proponents engaged and challenged their own chauvinism for the larger socialist project.

This is to say, that the marriage lasted, for better or worse, richer or poorer—until the house burned down in the catastrophe of 1989-91. Until the annulment, tiny East Germany strived to make its mark as an international player in building a socialist community.

As contributor Bernd Schaefer notes in his piece on how the GDR and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, “Unlike the asymmetric and often patronizing relations between the Soviet Union and other socialist states in both the Second and Third World, the East German capacity to contribute to the modernization of ‘fraternal countries’ in the Third World was smaller in scale but significant in substance.”

This meant that when faced with, for example, disparate notions of sexual politics with its African comrades, the GDR had to opt for the “pragmatic rather than the progressive.”

Nowhere was this made more evident than in the differing views of abortion. The GDR had legalized abortion at Erich Honecker’s initiative in 1971, while he was pushing a sort of sexual revolution. This did not jibe at all with Mozambican attitudes about women or their opposition even to the distribution of condoms.

Another example of this conflict came during and after the Communist Party USA’s Angela Davis’s 1970 arrest, trial, and acquittal almost two years later. Katrina Hagen’s piece notes how the GDR was swift in mobilizing grassroots support for Davis, culminating in a massive “1,000 Roses for Angela” letter-writing campaign by German students.

But how to deal with Davis was also a tightrope walk. In what foreshadows some of the differences between “ideas of socialism” and the “politics of FRELIMO,” a decade later, the more GDR officials became aware of Davis’s advocacy for Third World Black liberation struggles as racial struggles, the less comfortable they were. Nor was her work with the Black Panthers, a group that idolized Mao and de-centered the USSR in favor of China and Vietnam, a comfort. It was characterized by East German officials as “Black racism,” and they worried that she had veered from a class-based to a race-based revolutionary analysis. This kind of rhetoric did not connect with their own “ideas of socialism,” or their notion that the “key condition was to build the unity of the working class,” which steered clear of racial politics in favor of broader proletarianism

According to Hagen, the GDR instead played up Davis’s CPUSA credentials, the party’s history in organizing Black and white workers, and, strangely, her “good looks.” The “Angela Davis Story,” as seen through the sieve of the GDR media, is best exemplified by a 12-part biographical piece in the women’s magazine, Für Dich (For You), where Davis’s life is broken down as a “didactic story of socialist development.” (West Germany’s Der Spiegel, on the other hand, ran a contemporaneous story focusing on Davis’s “bourgeois respectability that middle-class readers could relate to.”)

The other Germany

The competing Germanys taking sides is a constant theme through this anthology, and a tension we’ve probably forgotten with time. The GDR had other motivations than just solidarity.

After being on the losing side in both of the 20th century’s worst wars, the two Germanys were in fierce competition with so many global actors. Each was eager to prove to the Western world and to the United Nations it was further away from the Third Reich than its opposite. Neither was admitted to the United Nations until the early 1970s because of that history and until then, West Germany was doubling down in its campaign to keep the GDR from being recognized at all. West Germany had to wear its anti-communism on its sleeve and prove to its masters it was on the right side.

Ahead of Angela Davis’s visit to the GDR, for example, West German diplomats, perhaps to solidify its role as Cold War ally to the United States and NATO, identified her in cables as “a militant activist of left-wing political extremism” and “a militant racial warrior,” and they described her supporters as “racial and worldview fanatics.”

But the book is not pure pro-GDR propaganda.

Slobodian includes in the anthology a 1968 piece that appeared in Red Guards of Shanghai, by a Chinese student studying in the GDR. The piece hearkens back to Dickens or to Upstairs Downstairs in describing East Germany and differs sharply from the image the state sought to project.

The Chinese student hits two bull’s eyes with one sharp pen, taking down both the revisionism he thought apparent in the GDR and the USSR for having betrayed the proletariat and set up a “bourgeois and fascist dictatorship.” Rather than a workers’ state, one finds in this piece a caste system of over-paid professor intellectuals who do little work and low-paid cleaning staff who work into their 80s, “one foot in the grave.”

“Power relations in the institutes are formed like pagodas and have a feudal coloring. Professors—doctors—assistants—laboratory assistants—material provisioners—cleaning staff—instrument cleaners,” the visiting Chinese student writes.

The SED [the GDR’s ruling Socialist Unity Party] is described as no better than a gentlemen’s club that adorns itself in Marxist baubles.

The GDR inadvertently planted the seeds of its own racial strife in handling the realities of a developing socialist state. This exploded later.

Tensions between the Mozambican students and East Germans erupted when their different value systems met headlong in local bars and discos, fueled by alcohol. Vietnamese workers trying to pick up East German women were often confronted and beaten up by East German men.

As Schaefer writes, by the late 1970s, the GDR had developed an extensive guest-worker program for Vietnamese, Mozambican, and Cuban nationals. These were prized jobs for the guest workers, brought in remittances to the families in the home country, and the GDR paid 12 percent of the guest-worker’s salaries directly to the home country government. This brought $35 million per year to socialist Vietnam. This was seen by East German elites as a win-win.

But guest-worker pay was much lower than that of their German counterparts, and these workers were increasingly used for more and more tasks to advance the GDR in comparison with its counterpart in the West. This fostered resentment among some East Germans who began to see these workers as depressing their own wages and stealing their jobs, while they had to endure deprivations.

Verber writes of a street brawl in 1986 between 50 Mozambican students, who had jumped the fence of the School of Friendship to confront over 100 East German youth.

This was not what East German officials had in mind by its “commitment to otherwise abstract notions like solidarity and shared struggle against imperialism.”

(The section “Training African students to be socialist leaders” in this recent article in People’s World also discusses this topic.)

The racial tensions boiling beneath the surface flowed over with the demise of the USSR and the socialist bloc and are painful to recall. Many were mystified to see the appearance of hateful forces that were reminders of another Germany of the 1930s. But other forces were unleashed after 1991. No longer faced with the pressures of a Soviet model, U.S. administrations set about to undo 45 years of social achievements. Bill Clinton dismantled the welfare system, sending more children into poverty than Ronald Reagan had. His wife employed the trope of “super predators” against Black men to push through some draconian laws to round up the inner cities. The prison population skyrocketed. With the destruction of the collective socialist endeavor, the nightmare resumed where it left off in the 1930s. So it is only in this context that the racist violence that emerged post-GDR seems logical.

On the other hand, studying these interactions between the GDR and the global South, as Slobodian has done broadly in this anthology, has current resonance. It is what we today call “culture wars” and “identity politics” in the West.

While the East German leadership was frequently confounded by some of the notions of their Mozambican brothers and sisters, their Maoist Chinese students, or how to handle a Black American political prisoner, the GDR did seem deeply committed to the project of making “otherwise abstract notions” of socialism that much more real. They didn’t seem guilty of the default position of so many white American leftists to exercise a kind of paternalism over Black and Brown members in their midst, because “the SED intended to prove that the notion of a shared struggle was more than just ideal talk and to put into practice their vision of socialist solidarity.”

We should understand the work the GDR was committed to and pick up the torch where it dropped.

Like free stuff? So do we. Here at People’s World, we believe strongly in the mission of keeping the labor and democratic movements informed so they are prepared for the struggle. But we need your help. While our content is free for readers (something we are proud of) it takes money — a lot of it — to produce and cover the stories you see in our pages. Only you, our readers and supporters, can keep us going. Only you can make sure we keep the news that matters free of paywalls and advertisements. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, support our work by becoming a $5 monthly sustainer today.

Comments