The English novelist Charles Dickens was born in 1812, during the Napoleonic Wars, into the lower petty bourgeoisie, whose life experience partly overlapped with that of the proletariat.

He died on June 9, 1870, at the age of 58. We write this on the 150th anniversary of his death.

Although Dickens’s authorial perspective always remained petty bourgeois, he never forgot how his father was imprisoned for debts and that the financial circumstances of his family forced him to leave school at the age of 12 and work a 10-hour day in a blackening (shoe polish) factory. This experience led to his lifelong conviction that no child should ever endure such suffering.

Apart from witnessing poverty and child labor, Dickens also experienced the efforts of the petty bourgeoisie to keep up some kind of façade in the face of financial hardship. Despite his incredible early literary success, Dickens never became complacent. Instead, his radicalism deepened over the course of his life.

Dickens’s first journalistic jobs were as a parliamentary reporter for radical magazines, thus moving in radical circles. He was also instrumental in organizing a strike by the reporters of the newspaper The True Sun and successfully acted as their spokesperson.

At the same time, his love of writing developed. In 1836, he gave up his job as a reporter and started to earn his living by selling his books and writings.

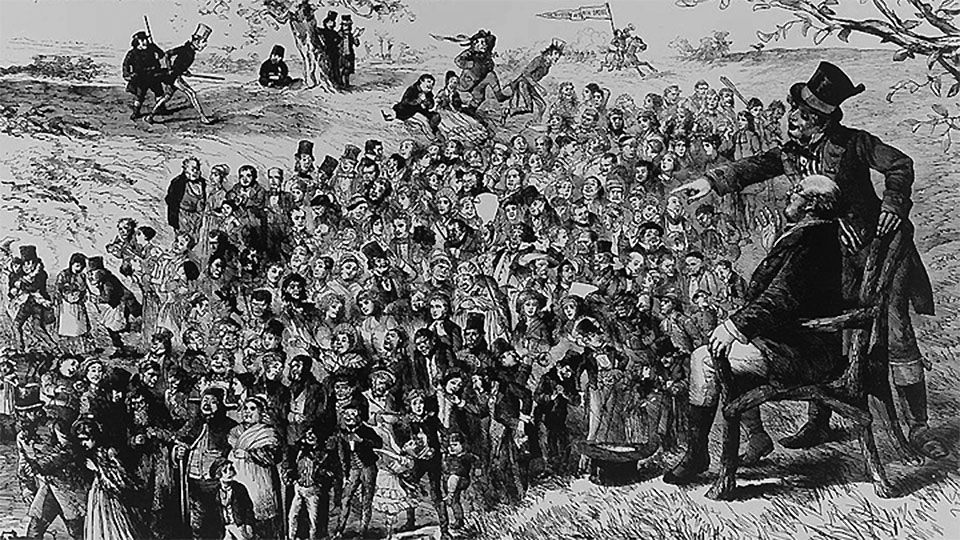

He was born into the rapidly accelerating period of the Industrial Revolution, which powered the transition of British capitalism into its imperialist phase. His first creative period from 1836 to 1842 coincided with the rise and peak of the Chartist movement. His second phase covered the temporary revival of Chartism and the upheaval of 1848-49, ending with the final triumph of European reaction in 1850, a triumph that marked his third creative period.

Dickens’s development as a writer, from a basic outlook of optimism to one of pessimism, thus reflects the sensitivities of English radicalism in those same years. His productive literary work falls into the period between the collapse of the English socialist movement under Robert Owen, and its revival under the First International in 1864. In France, the painter Gustave Courbet developed realism during this epoch, depicting people at work in an unromanticized way. This speaks to the spirit of the times, the context in which we must seek the significance of Charles Dickens.

Dickens always regarded himself as one of the common people, sympathizing with them as working people and exposing injustice against them. This made him lastingly popular with ordinary folk. His stance that the poor, and socially excluded groups like children, be treated as human beings was in itself a revolutionary demand.

Taking this position, Dickens developed a new type of novel. His novels take the focus away from characters in the wealthy classes and toward the lives of ordinary, mostly urban children, men, and women, who grapple with everyday challenges. With his strong sense of individuality, he made these people extraordinarily vivid. He shows his readers the darker side of society in the first great industrialized metropolis in the world. His most interesting and valuable characters are usually people from the lower social classes.

In 1842 Dickens traveled to the United States as a committed supporter of American independence, seeking to find the democracy of his dreams. Not only was he disappointed in what he saw, but the existence of slavery and its enthusiastic defense by many he met also outraged him. After his return, he wrote American Notes for General Circulation (1842), which strongly criticized American society and its values, especially slavery and violence, as well as its extreme individualism. In the novel Martin Chuzzlewit, published shortly afterward, he also described the conflict he experienced between expectations and reality in the U.S.

Until his visit to the U.S., Dickens’s perspective was directed exclusively toward southern England, while the main impulse for Chartism came from the industrial Midlands and the North. Not surprisingly, the radicalism in his earlier novels was more moderate and initially represented incidental ills. But as his writing developed, the entire social system that he depicts increasingly proves to be deeply rotten and unreformable.

Great Expectations

By way of example, let us turn briefly to one of Dickens’s later novels, Great Expectations (1860-61), in which the title-giving expectation is borne by a boy from the working class and is attached to the hope for a wealthy patroness’s goodwill. The novel describes Pip’s development and the shock of disillusionment.

In this book, there is absolutely no hope that conditions could be put right by the benevolence of the ruling class. Instead, it is the outcast Magwitch, cheated, exploited, and brutalized by the law, who shows gratitude and generosity to Pip. Just as the bourgeoisie owes its wealth to the exploitation of the working classes, so Pip owes his wealth to Magwitch—and Pip is just as ungrateful as the bourgeoisie.

Dickens’s depiction of the two lawyer characters, Jaggers and his employee Wemmick, is also noteworthy. They are ruthless in their working lives, but they lead a completely different, compassionate private life, showing that success in business is only achieved at the expense of one’s own humanity. To underline this metaphorically, Jaggers always washes his hands following a particularly dirty job. Pip also changes during the time of his “expectations,” at the expense of his humanity, as is painfully expressed in his shameful treatment of Joe Gargery and Biddy.

The novel shows the folly of indulging in illusion, and how the lure of great expectations leads to disaster. Dickens’s original ending underlined Pip’s complete break with his aspirations for social advancement and his insight into the heartlessness of “better” society. However, Dickens let himself be dissuaded from his planned, mercilessly consistent novel ending. Under pressure from the novelist Bulwer Lytton, he changed his intended ending in favor of a less likely, happier outcome. One is inclined to agree with George Bernard Shaw, who stated that Dickens’s original conclusion was the true happy ending. The logic of the novel contradicts the changed ending. Its most admirable characters are the blacksmith Joe Gargery and the teacher Biddy, Gargery’s second wife. Pip himself, as the main character, begins and ends as a working person.

When Charles Dickens began writing in 1836, the literacy rate in England was under 50 percent. More than any other writer of his time, Dickens must have helped inspire a desire for literacy among the ordinary people, by publishing stories—mostly serialized in magazines—that people really wanted to read because they could relate to the characters.

Dickens has had a great and continuing influence on subsequent writers. For example, in Robert Tressell’s Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists, not only does Tressell expand on Dickens’s focus by depicting a panorama of working-class people, but he is also clearly steeped in the Dickensian tradition in his use of names or motifs, which contain the power of social generalization. In this sense, Dickens’s increasingly fierce and pointed satires help prepare the ground for true working-class literature.