From March 9-11, 2023, the African American Intellectual History Society (AAIHS) held its annual conference in Charlotte at the University of North Carolina Du Bois Center. Dozens of panels and workshops took place, as scholars discussed several topics, including “Racial Theories and the Black Intelligentsia,” “Contestations Against Police Violence,” “Black Women Envisioning Transformation,” “Policing and Resisting State Violence,” among others.

Tony Pecinovsky, People’s World contributor and author of The Cancer of Colonialism: W. Alphaeus Hunton, Black Liberation, and the Daily Worker, 1944-1946, participated in a Roundtable Discussion titled “Policing the Black Scare and the Red Scare.” He, and the other panelists, Charisse Burden-Stelly, author of Organize, Fight, Win: Black Communists Women’s Political Writing, and Denise Lynn, author of Where Is Juliet Stuart Poyntz?: Gender, Spycraft, and Anti-Stalinism in the Early Cold War, discussed how the Black Scare and the Red Scare are mutually reinforcing and serve to delegitimize anti-capitalist discourses while also criminalizing African American struggles for civil rights, equality, and liberation.

Below is a slightly expanded version of Pecinovsky’s presentation.

First, let me say what an honor it is to be presenting at the African American Intellectual History Society annual conference. Also, it is an honor to share a panel with Charisse Burden-Stelly and Denise Lynn.

Before I begin, we should—at some point—pause and honor the life and contributions of Charlene Mitchell, who passed in December of last year.

My talk today deals primarily with myths, and how we must disrupt and challenge myths if we are going to effectively challenge racism and white supremacy.

I’m just going to jump right in.

What is a myth? According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, a myth is:

“a story of historical events that serves to unfold the world view of a people or explain a practice, belief, or natural phenomenon;

“a popular belief or tradition that has grown up around something or someone especially one embodying the ideals and institutions of a society;

“an unfounded or false notion; or

“a person or thing having only an imaginary or unverifiable existence.”

The United States was founded on a number of myths. Among them are white victimization, capitalist progress, and the self-made man. These myths—among others—shape how many Euro-Americans think about themselves. These myths lay at the heart of ruling class justifications for settler colonialism, slavery, imperialism, war, and racial capitalism. They also serve to justify the ongoing assault on Black lives.

In essence, myths police our society.

Denise explained how the Red Scare was used to discipline and silence Roosevelt Ward, a Black Communist imprisoned due to his peace activism. By the time of Ward’s 1951 arrest, the myth of Communist subversion permeated our society. In her presentation, Denise used the phrase, “imagined threat to the state.” This is important. The FBI “imagined” that Ward was a threat. Like other Communists, he had taken no overt act to subvert the U.S. government.

Throughout the 1950s, this myth—that the Communist Party USA sought the violent overthrow of the U.S. government—justified thought control laws, such as the McCarran Internal Security Act. It justified Subversive Activities Control Boards and House Un-American Activities Committees.

This myth destroyed some of the most important civil rights organizations in U.S. history, such as the Civil Rights Congress and the Council on African Affairs.

This myth largely targeted Black radicals—Paul Robeson, Claudia Jones, William L. Patterson, Alphaeus Hunton—and the organizations they led.

Charisse explained how the Black Scare criminalized and condemned critiques of police brutality. The myth of Black criminality was—and remains—a key component of a strategy to debase, distort, and subject Black people. At the heart of the Black Scare is the idea that Black agency itself is a form of radicalism because it is a fundamental challenge to white supremacy.

The Black Scare characterized marches and protests as dangerous, engineered by Communists at Moscow’s behest. This myth transformed and distorted Black demands for equality and civil rights into something un-American.

Of course, we know this narrative is just as fanciful as the QAnon conspiracies today.

To be clear, Communists—in particular, Black Communists—did make important contributions throughout the 1960s. Debbie Bell, a field organizer for the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee; Esther Cooper-Jackson, a co-founder and managing editor of Freedomways magazine; and William L. Patterson, known as “Mr. Civil Rights,” are just a few.

And here, in the Du Bois Center, we must not forget that W.E.B. DuBois chose to officially join the CPUSA in 1961.

Which gets me to the main point.

The neglect of Black woman Communist Charlene Mitchell is an example of the ahistorical nature of the myth that the CPUSA became a marginal political force post-1956. It is a myth that serves to constrain the boundaries of political discourse, a myth that polices our society and history, and as a result, impacts the strategy and tactics we employ today in the struggle for equality and liberation.

To decouple Mitchell, the CPUSA, and world socialism from the struggles against racist and political repression in the 1970s and ’80s is to relegate Black Communist women’s radical activism to the margins. It is to ignore the fact that the CPUSA, despite its reduced size, still provided a pathway for Black working-class women’s agency, continued to challenge capitalist hegemony—and helped win some very important victories.

As you may know, in 1968 Mitchell became the first African American woman to run for president of the United States. She reflected a vision of the left rooted in the experiences of working-class women of color.

However, her campaign, as historic as it is, was just a prelude.

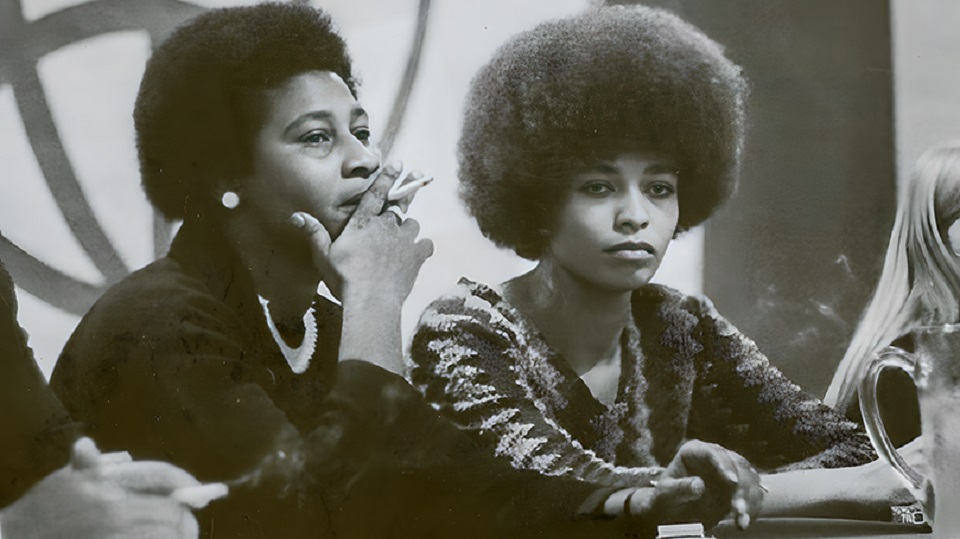

We’re all well aware of the Angela Davis case—her frame-up, trial, and acquittal in June 1972.

What is sometimes forgotten is that it was Charlene Mitchell who was the executive director of the National United Committee to Free Angela Davis, which grew to over 200 chapters nationally and inspired one of the largest global campaigns for freedom in history.

Like so many Black women before her, Mitchell did the unglamorous, grunt work of organization building.

Just as importantly, shortly after the Davis acquittal, in May 1973, the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression (NAARPR) was born—led by Mitchell.

A review of the Alliance’s founding documents, newsletters, reports, and papers, as well as Mitchell’s unpublished autobiography, foregrounds its pioneering role, while also placing it within a larger Communist tradition stretching back to the defense of the Scottsboro Nine.

Mitchell wrote, “it seemed as though people were waiting for [the Alliance]. We were just swamped with work. Of course, we also had to contend with latent and blatant anti-communism. People were always whispering, ‘Well, [the Alliance] is controlled by Communists.’ Sometimes it seemed as though I spent as much time fighting anti-communism as police crimes.”

Despite the redbaiting, the Alliance focused on the South, a region not known for its progressivism.

Interestingly, the Alliance got its start—in a way—in North Carolina. As Mitchell wrote, North Carolina “was almost a template…the degree of oppression [there]…was really amazing.”

The Alliance jumped in with both feet. In July 1974, it led 10,000 people past the Central Prison in Raleigh—two and a half hours from here—to protest the so-called “administration of justice.” North Carolina then had 45 people on death row—more than any other state—with 14,000 people then incarcerated, “one of the highest prison ratios in the nation.”

The coalition the Alliance built included the Rev. Ralph Abernathy, head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the National Lawyers Guild, and the National Conference of Black Lawyers, among others. Together, they collectively brought attention to police brutality and death and prison sentences disproportionately handed out to people of color.

As Mitchell wrote, “More and more, Black people…understand the direct link between racism and repression, between racism and arrests, and between racism and prison conditions, which create prison rebellions.”

With this in mind, the Alliance also helped organize legal defense for victims of racist and sexist repression. For example, Joan Little, 20, a North Carolina working-class Black woman, was facing the death penalty in 1975 for killing a white male prison guard. The prison guard attacked her with an ice pick, intending to rape her.

The Alliance put Little’s assault into political context. She became “a symbol of the economic exploitation, sexual violation, political persecution, and denigration of Black womanhood,” as Erik McDuffie noted in Sojourning For Freedom.

Mitchell told Little, “…We’ve got to get across to these damn jurors that you were defending yourself and that you had every right to defend yourself…” Apparently, to some white jurors, self-defense against rape was a radical idea.

Ultimately, Little became the first Black woman in U.S. history to be acquitted of killing her white attacker by arguing that she “used lethal force in self-defense against rape.” This was in August 1975.

These are just two examples of Mitchell’s and the Alliance’s leadership—leadership that brought mass action, legal pressure, and international attention to domestic struggles against racist and political repression, a unique brand of working-class Black women’s activism.

Mitchell’s and the Alliance’s work also demonstrate the continuities in Black Communist women’s radical activism spanning from the 1930s to the 1950s, and into the 1970s and ’80s.

I can only scratch the surface of the Alliance’s history. However, by illuminating the work of Charlene Mitchell and the Alliance, we illuminate a neglected aspect of Black resistance to police brutality, racist and political repression, and the links these struggles have to the CPUSA and world socialism.

Additionally, we disrupt another of the dominant myths of U.S. society. Just as the Red Scare is used to police and condemn anti-capitalist ideas, and the Black Scare is used to debase, distort, and criminalize Blackness, the myth that Communists—particularly Black Communists—became a marginal political force post-1956, serves to cripple our collective resistance to racism.

If we are to challenge racism in all of its manifestations, it is imperative that we disrupt the underlying, foundational myths that support white supremacy.