“Heaven is a large place,” one of heaven’s head clerks says in Mark Twain’s story, Extract from Captain Stormfield’s Visit to Heaven. “Large empires have many diverse customs.” In the short story, Stormfield accidentally arrives at the wrong heaven after racing a comet on the way to his final home. He must engage with a bureaucratic nightmare at the gate that’s “billions of leagues from the right one,” before getting to the gate for his solar system (the angels (clerks) at the first heaven are unaware of Earth and find it on a map listed as “the Wart”.

In Divided Heaven, a popular 1963 novel by East German writer Christa Wolf, lovers Rita and Manfred are separated between the two Germanies—Manfred moves to the West and Rita stays in the East. “But even if our land is divided, we still share the same heaven,” says Manfred. “No” Rita replies, “they first divided the heaven.”

Both stories highlight how our material conditions shape our images of other worlds, divided by customs, language, and daily life. As Twain put it, “I have traveled more than anyone else, and I have noticed that even the angels speak English with an accent.”

Dissolve the people

In the late 1980s, West German director Wim Wenders secured a meeting with the Minister of Culture of the German Democratic Republic (GDR/East Germany), Hans-Joachim Hoffmann, in anticipation of filming Wings of Desire.

One of the few Wenders films that had been shown in East Berlin up to that point was Paris, Texas, the chronicle of Travis, an alienated individual searching for his lost wife. While the motif was clearly critical of American capitalism, Wenders remained unwitting, claiming that the film was screened in the GDR because “for some reason they decided it was an anti-capitalist movie.”

Wenders hoped that his session with Hoffman could score an approval for Wings of Desire, too. Hoffman, while he’d been a fan of Paris, Texas, was not, as might be expected during the Cold War, keen on the idea of a scriptless film about angels who can move through walls. The movie failed to get the green-light to appear in GDR cinemas.

Frustrated by the decision of the cultural commissar, Wenders might have recalled the famous playwright Bertolt Brecht, who’d been critical of the GDR’s leadership in the 1950s. He became known by many in the West for a section of his sarcastic poem “Die Lösung” (“The Solution”), about the GDR’s response to the 1953 workers’ uprising:

“Would it not in that case

Be simpler for the government

To dissolve the people

And elect another?”

But Brecht and writers like Divided Heaven’s Wolf never mistook their internal qualms with bureaucracy for an endorsement of capitalism or anti-communism. Wolf was herself a member of the ruling Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), and Brecht formed the Berliner Ensemble in East Berlin, remaining an ardent Marxist after escaping Nazi Germany and McCarthyite America. They still believed wholeheartedly in a socialist future for Germany.

In the case of Wenders, it would seem he wanted to dissolve political people altogether and elect no one.

Mercedes-Benz suicide

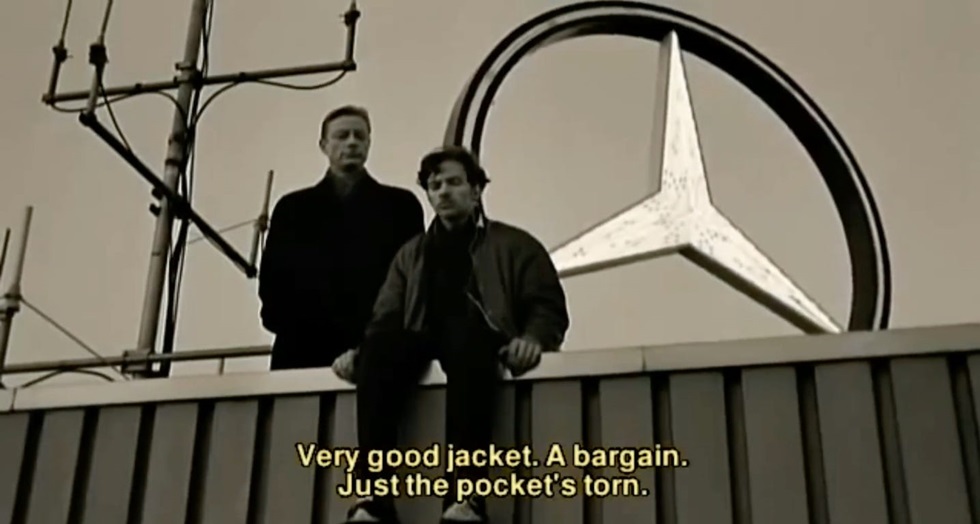

The decaying, yet colorful, image-obsessed depiction of America in Paris, Texas couldn’t be further from Wenders’ Berlin. Wings of Desire depicts a West Berlin that more closely resembles stereotyped images of the socialist bloc, with gray buildings and anxious inhabitants. Wenders reverses this image, holding up a mirror to a capitalist dystopia rampant with homelessness, suicide, and rockstars singing about 17-year-olds. Even the circus is depressing. In a pivotal scene, a young man with headphones is sitting on a building with the Mercedes-Benz sign spinning above him before he jumps to his death.

In the film, two angels named Damiel and Cassiel have existed in Berlin since long before it was a city and up through the rule of the Nazis. But it’s not until 1987 in West Berlin that Damiel is inclined to give up his wings and become human, inspired by a conversation with the actor Peter Falk (Columbo), a former angel himself. When Columbo gives his monologue to Cassiel, however, Cassiel stays back and grins, apparently unswayed by the actor’s charming pitch. The implication is that Columbo can sense the presence of angels being a former one himself.

But a far more critical reading could be employed here: Columbo doesn’t sense angels at all; he was actually just a madman delivering a sales pitch for a pyramid scheme called life. Columbo, a man living on the capitalist side of the world and knowing his new angel recruits would be homeless and hungry, could convince these angels, who presumably have no desperate need for housing and food—an oft-overlooked staple of developed socialist countries—although it might seem like an overly economic-determinist view, is the real story of a divided Germany.

Lederhosen in the GDR

“For the first time I have a painful sense—not simply a rational one—of the tragedy of our two Germanies,” wrote the East German writer, Brigitte Reimann, after her brother moved to West Germany. “Torn families, opposition of brother and sister—what a literary subject! Why is nobody taking this up, why is no one writing a definitive book?”

She took it upon herself and wrote the 1963 novella, Siblings, a story mirroring her experience seeing her brother defect; Reimann followed Wolf and Brecht’s dual criticism of and support for a socialist Germany, telling personal stories of average workers and also organizing through Writers’ Union workshops like one at a lignite plant in Hoyerswerder.

Reimann and Wolf’s novels express, as Dr. Jenny Farrell noted, “women’s confidence in their social equality to an extent that is unparalleled in Western literature and society at that time.” Women’s equality is just one aspect of socialist culture that has been forgotten; another is the story of many defectors going to the East, including American soldier Victor Grossman, who escaped political persecution in the U.S. by swimming the Danube River.

Despite the torn Berlin in Wings of Desire, none of the color that’s so visible in the novels of the GDR translate into Wender’s politically innocent world. “Every person is a universe all by itself,” Wenders said in an interview. Heaven is divided. Wenders presents a capitalist dystopia that seduces the very bureaucrats of heaven (Cassiel gives in to becoming human in the second movie). Meanwhile, West Berliners in the early years would traverse the border to exploit the subsidized food prices—I recall a specific conversation with longtime labor organizer Scott Marshall who remembered visiting the GDR after the Wall went up and constantly running into American G.I.s who’d crossed into East Berlin to purchase lederhosen.

In a TikTok satirizing a tour through the DDR Museum, the tour guide describes the difficult conditions East Berliners witnessed: “They were given an apartment by the state and the apartment was very small. It was free, but it was very dark.” The video shows images of a spacious fully furnished apartment that, if it was located in Manhattan today, would likely sell for a million dollars. The fictional visitor promptly punches the guide. Grossman, the American defector, reflected himself that he only ever paid between 5%-10% of his income on rent in the GDR, which he contrasted to his hometown in the U.S. (even today, the U.S. considers housing affordable when 30% or less is spent on rent).

Much like Rita in Divided Heaven, Grossman, and Brecht, many are coming to a more nuanced understanding of the history and political project of building socialism, one that is imbued with criticism, yes, but also with a belief in moving past a self-destructing world of war and profits. Here is where Wenders and many Western films fall tragically short.

“The worst illiterate,” Brecht formulated, “is the political illiterate… He doesn’t know the cost of life, the price of the bean, of the fish, of the flour, of the rent, of the shoes, and of the medicine, all depends on political decisions.” That Wenders made films critical of capitalism appears to fall on his own deaf ears.

Wings of Desire shows that it’s not only easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism, but that it’s even harder to imagine a heaven after capitalism. One is left seriously questioning the character of angels who, after witnessing all of history, wait until the peak of capitalism in West Germany to check out. To quote Twain, “When I reflect upon the number of disagreeable people who I know have gone to a better world, I am moved to lead a different life.”

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today. Thank you!

Comments