Famed Irish playwright Sean O’Casey’s only daughter and now sole surviving child, Shivaun, has gifted the worldwide O’Casey community a splendid memoir of her life in the O’Casey family. Shivaun O’Casey was born in 1939, at the dawn of the Second World War, into a household where politics and artistic practice were inseparable from daily life. Her father, Sean, then 59, and her mother, Eileen, 20 years younger, were politically aware people; Sean defined himself as a communist for the best part of his life, and until he died aged 84, in 1964.

The family home was a hub of the cultural front of mid-century socialism. The children were sent to the progressive, Fabian-linked Dartington Hall school at the suggestion of family friend G.B. Shaw. Among their many left-wing friends was Communist Party of Great Britain leader Harry Pollitt, and the house was filled with modernist art and Van Gogh prints. They were familiar with the Eisenstein films and the Jooss Ballet.

Yet ideological and aesthetic richness existed alongside real material scarcity, navigated through constant financial strain, bartering, and the solidarity of taking in evacuee children. From the outset, the memoir presents a world where politics was not theory but lived praxis, woven into family, art, education, and survival.

The end of the war was a slow transition marked by the rationing of bread, clothes, and meat, the lifting of the blackout, before fully returning to normality. The horrors of the concentration camps were brought to them, as witnessed by friends like Sidney Bernstein. Eileen O’Casey observes how the wartime sense of collective purpose faded, and people “drew back into themselves.”

Inside the often cold, damp house, the family maintained its distinctive rhythms. Sean, his eyesight deteriorating, had to keep a meticulously recreated version of his first Dublin room to find the books or papers he needed. He worked at night, “an old habit from his days as a workman in his one room in Dublin,” and was a storyteller who made pipe-cleaner figures and sang to Shivaun.

Eileen faced early school mornings with difficulty while confronting endless financial pressures with creativity—drawing comics, singing, even pawning her engagement ring to fund trips to London. The family’s “tablecloth was the Daily Worker.” Alongside these memories is the intimate, recurring task of plucking painful eyelashes from Sean’s eyes and the trove of unpublished family letters and drawings.

The children moved through this politically charged world: Breon heading into National Service, Niall and Shivaun adapting to Dartington Hall, rescuing kittens, and Sean’s letter to the principal on educational philosophy: “As a Communist, I am in favor of preferential treatment to all in all schools—that is the adapting of educational methods to each child according to its needs.”

All of this unfolded against the backdrop of rebuilding prefabs, the freezing winter of 1947, recurring money worries, and the doctor-ordered room rearrangement forced by Sean’s worsening sight. Yet, the O’Caseys protected a fragile but real sense of normality. Their post-war story is one of meeting hardship through routine, storytelling, and the persistent, defiant presence of art.

The chapter on his play Purple Dust captures both Sean O’Casey’s creative passion and the precariousness of his professional circumstances. His agreement to travel to London and stay with U.S. director Sam Wanamaker revealed unusual enthusiasm and a strong personal rapport. He contributed actively to rehearsals, writing additional songs for the production team—including composer Malcolm Arnold and choreographer John Cranko—and entrusted the work to a cast led by Siobhán McKenna.

Yet the project was not the success it deserved: poor reviews in Glasgow, partly attributed to Catholic sentiment, and a dispirited performance by Miles Malleson all undermined it. Despite admiration from figures like Charlie Chaplin, Purple Dust never transferred to London. Financial troubles at home worsened, culminating in a bailiff arriving at Tingrith.

The 1955 Dublin production of The Bishop’s Bonfire was a defining and painful moment in O’Casey’s fraught relationship with Ireland. Its premiere at the Gaiety Theatre—staged by Cyril Cusack, directed by Tyrone Guthrie, and attended by Eileen and Shivaun—descended into a first-night riot, likely sparked by members of the Legion of Mary, an international association of members of the Catholic Church who serve on a voluntary basis. At one point, a couple of protesters stood up, said something, and began “chucking down leaflets,” provoking such a furore from the audience that the performance had to be stopped.

As Eileen remarked, “They want it to be like the riots at the Plough.” Though Cusack restored order, the critical backlash endured. Gabriel Fallon, once a friend, delivered savage reviews that condemned the play’s anti-clericalism and permanently ruptured their relationship. While British reviews were more positive, hopes for a London transfer evaporated. The episode deepened O’Casey’s bitter and lasting estrangement from the Irish cultural and religious establishment he had spent a lifetime challenging.

In 1957, tragedy struck the family when Niall died suddenly of an aggressive form of leukemia—a loss from which they never recovered. The memoir portrays the private grief that followed: Sean keening alone in his room, Eileen numbing herself with secret drinking, and even attempting suicide.

For O’Casey, theatre was a battleground of ideas. His conflict with the Irish establishment—beginning with Yeats’ rejection of The Silver Tassie in 1928 and culminating in the Archbishop McQuaid-driven Tostal Affair of 1958—defined a career shaped by resistance. Riots over The Bishop’s Bonfire and the break with Gabriel Fallon were not mere disputes but episodes in an Irish cultural Cold War, pitting his radical vision against entrenched theocratic conservative power.

In Britain, he faced different constraints: the Lord Chamberlain’s censorship and the commercial prejudices of the “Grandees of the Theatre,” which drove political works like The Star Turns Red into left-wing venues such as the Unity Theatre. Shivaun’s memoir highlights the sustenance the family drew from international models: the Moscow Art Theatre and the GDR’s Berliner Ensemble, embodiments of how political art could thrive under supportive socialist state institutions rather than hostility.

The Tostal Affair saw Archbishop John Charles McQuaid’s objections to O’Casey and Joyce force the withdrawal of The Drums of Father Ned from the 1958 Dublin Theatre Festival. The act crystallized O’Casey’s lifelong fight against Irish conservatism and led to his principled response: a self-imposed ban on professional productions of his plays in Ireland, maintained until 1964. In a striking moment of solidarity that marked a significant breach in Irish cultural life, Samuel Beckett withdrew his own work in support, exposing the deep divide between the nation’s artistic innovators and its authoritarian establishment.

Shivaun’s journey across the United States illuminated the breadth of admiration for her father abroad, sharply contrasting with the hostility he faced in Ireland. She encountered a devoted U.S. cultural network—critics like Brooks Atkinson, Carlotta Monterey, and producer Lucille Lortel—demonstrating O’Casey’s stature as a major literary figure. This esteem translated into artistic activity: Paul Shyre’s staged readings of I Knock at the Door and Pictures in the Hallway won awards, and the early development of the musical Juno by Marc Blitzstein and Joseph Stein showed continuing U.S. interest in his work.

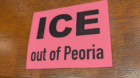

Shivaun’s 1957–58 tour diary offers a firsthand view of the nature of the U.S. empire. She records the shock of Jim Crow segregation, the poverty of Black sharecroppers and Native American reservations, and the ominous spectacle of Ku Klux Klan rallies—evidence of internal colonialism as well as systemic racism and exploitation.

The lingering chill of McCarthyism appears in the “strong silence” after she acknowledged Sean’s communism on television and in her meetings with blacklisted friends such as the Wanamakers. Other blacklisted U.S. friends, Don Stewart and Ella Winter, Shivaun had already met in London. A central irony runs through the tour: its financial dependence on conservative Catholic colleges, even as the same forces had banned her father’s work in Ireland, revealing a transnational alliance between religious conservatism and anti-communism eager to appropriate “Irishness” for ideological ends.

The political becomes personal when she links Cold War violence to family tragedy, performing at White Sands Missile Base while believing that Niall’s leukemia resulted from U.S. nuclear testing. Yet the memoir also maps a resilient internationalist cultural front: Paul Robeson, Charlie Chaplin, blacklisted artists, Soviet publishers, Samuel Beckett, Harold Clurman, Brooks Atkinson—a network in which O’Casey stood as a vital node. Across these connections, artistic struggle and political resistance remain inseparable.

Through Shivaun’s intimate narrative, Sean O’Casey emerges as an engaged and persistently relevant revolutionary artist, whose battles against clerical repression, capitalist theatre, and imperial power echo sharply today. The many detailed footnotes furnish readers with additional information, sources, and links.

The memoir’s power lies in binding his political legacy to the human scale: Sean’s love for Eileen and his children, his grief for a lost son, his anxieties over bills, failing eyesight, and relentless writing. It shows the personal cost and the unyielding necessity of a life committed to his “burning ambition…that I and all might be able to live a full life.” And it gives a wide-ranging scope of the whole of O’Casey’s work, which in Ireland and Britain is too often limited to the three Dublin plays and outside the Isles is known little at all.

The memoir is essential reading—a vital account of the historical intersections of communism and culture, and of the enduring work of solidarity, resilience, and bringing a radical vision to a hostile public stage. It is long past time for the English-speaking theatre world to look beyond the familiar Dublin trilogy and bring the full range of O’Casey’s repertoire back into view, where its breadth, defiance, and relevance can be fully felt.

Next Year will be a Good One. Life with Sean O’Casey, my family and theatre

By Shivaun O’Casey

Belcouver Press, 2025.

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today.