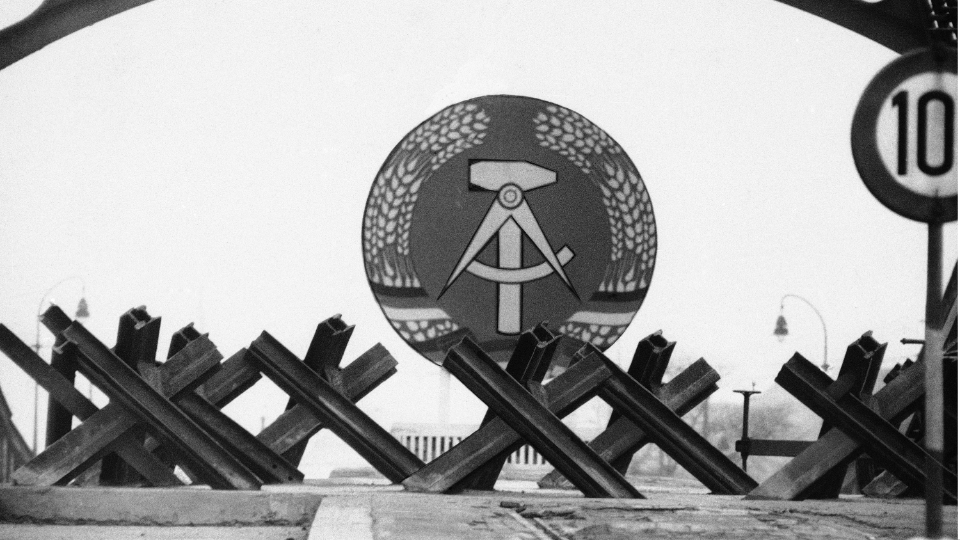

The German Democratic Republic (1949-1990) has long been a subject neglected by many historians—or, if it is given attention, it’s been portrayed simply as a totalitarian country ruled by Stalinists who oppressed the population. Katja Hoyer’s new book on the GDR, Beyond the Wall: East Germany, 1949-1990, in its British edition, soon to be published in the U.S., is being promoted as “the definitive history.” There is, of course, never a definitive history of any period, and this book, like any other, has been written through a particular ideological lens.

However, Hoyer, who was born in the Deutsche Demokratische Republik five years before its demise, does present a more differentiated picture from that to which we have become accustomed. Her aim is to give a more comprehensive description of the GDR, its difficulties and achievements, and thus reintegrate it as part of German history. A fair portrayal of the political situation in the middle of Europe at the interface with NATO, and of the real-life experiences of GDR citizens, is urgently needed for a better understanding of Germany today. And Hoyer has produced a very readable book that includes many personal stories which create a vivid picture that could help readers understand the real history.

Although more information about the GDR is most welcome, the book still feels unbalanced. Before she begins to deal with the GDR itself, she devotes around 150 pages almost entirely to the violence and the purges under Stalin in the Soviet Union during the 1930s and then the “invasion” of Berlin by Soviet soldiers who violate women and are described in the same style as a “drunken horde of foreign invaders.” No recognition here of our ally at the time, the Soviet Red Army, liberating Germany from the scourge of Nazism. Furthermore, the alleged power struggle between the first GDR leaders, Walter Ulbricht and Wilhelm Pieck, is given undue prominence, whereas hardly anything is said about the nature of the new society that was being built by so many.

By depicting the attempt to construct a new anti-fascist society as simply an imposition by a small political elite, forcing the people to make do and accommodate themselves to this new reality, the author ignores the considerable contributions made by so many genuine anti-fascists and socialists at the grassroots level. In this sense, Hoyer’s book only underlines the mainstream Western narrative of the GDR as a totalitarian state with few, if any, redeeming features.

Missing in her book, for instance, is an analysis of the different ways East and West were dealing with the post-war de-Nazification as laid down in the Potsdam Agreement. Hoyer sees de-Nazification more as an economic rather than a political question. While West Germany (the Federal Republic of Germany—FRG) introduced a law in 1953 that allowed former Nazis to return to their positions as army officers, lawyers, and teachers, the GDR removed most former Nazis from public office and was therefore obliged to rapidly train new people in these professions. This was of central political importance for the society the GDR set out to build, even though, initially, it had negative economic consequences.

Hoyer details the political and economic difficulties that led to the building of the Wall and writes about the relative economic stability achieved in the GDR after it was built. A sealed border put a stop to the steady hemorrhaging of professionals, academics, and skilled workers who, after completing their professional training, were, in the main, attracted to the West by the much higher wages and material standards of living. But by stressing in great detail the measures taken to prevent people fleeing the GDR, including the border shootings, the impression of a police state is reaffirmed.

Aside from some cursory comments about how East Germans wanted to build a state markedly different from that of the Nazis, only halfway through the book is the reader given any real inkling of what life was actually like for GDR citizens. Hoyer implies that the first decades were primarily about overcoming huge political and economic difficulties and that only from the 1970s onward did the benefits of childcare provision, comprehensive education, and support for recreation become freely available. While life did become more prosperous, the principle of free access to education, health provision, and childcare was there from the very early days.

It is disappointing, too, that the vast majority of the personal stories Hoyer retells are negative. They convey the impression that these are representative stories typical of life in the GDR. Yet there are many other potential stories about the excitement of helping to build something new, be it in industry (the battle for energy resources), agriculture (building of new agricultural structures and the sharing of technology), education (workers’ and peasants’ academies), or art (bringing artists and workers together). Apart from talking about the two pop stars Frank Schöbel and Dean Reed and a rock group, she does not cover the rich cultural life in the GDR—literature, theater, visual art, and musical life.

While Christian religious institutions played a not insignificant role in the GDR, relations between the ruling Socialist Unity Party and church were at times strained. Hoyer mentions the tension between state and church that came about with the introduction of the Jugendweihe (a secular form of confirmation for young people) but without further explanation. Jugendweihe is a coming-of-age celebration with a long tradition in Germany which goes back to the 19th century when it was introduced by the Free Masons. During the formation and consolidation of the GDR, religiosity among the people declined significantly, and an overwhelming number of 14-year-olds were welcomed into adulthood through the secular Jugendweihe, which became an accepted and popular rite of passage.

One of the progressive aspects that characterized the newly established GDR was its new constitution, particularly the fact that in it women were guaranteed equal rights. Hoyer ignores this, even though the contribution of women made a huge difference in the construction of that new society. She does refer to gender equality in the 1970s (and contrasts it with the situation in the West), but ignores the fact that gender equality had been a crucial factor already in the early years of the GDR. The independence and self-confidence of GDR women were much commented on by West Germans after the Wall came down, but this had been achieved because of the rights women had enjoyed over decades.

Hoyer talks about car ownership and the difficulties of obtaining a new automobile but does not mention the well-developed and subsidized public transport system. By leaving these facts out of her narrative, the reader cannot really understand why, in 1989, many people in the country were looking for a reformed GDR rather than its abolition and annexation by the FRG.

It is surprising that Hoyer does not mention the sanctions imposed by the West on the GDR (similar to those imposed on Cuba by the U.S.) throughout its short existence. She mentions the Hallstein Doctrine but not what impact it had on the GDR economy. It created almost insurmountable difficulties in terms of the introduction of modern machinery as well as research and development. Complex initiatives had to be taken in order to help overcome its effect.

The considerable contribution to international solidarity made by the GDR is also left out of the narrative. Its significant support for countries struggling for national liberation in Africa, Vietnam, and Latin America is ignored. The GDR offered schooling and traineeships to many young people from the so-called “Third World.” Hoyer uses the term “contract workers” when commenting about this, but that is to misunderstand this form of support. Those who came to study and train in the GDR could not be compared with the so-called “guest workers” in West Germany. Unlike those workers, who often toiled for low wages, the young people who came to the GDR received an apprenticeship or engineering qualification and then returned to their countries to help build the infrastructure of their homelands. This was a form of solidarity, not economic exploitation. (One exception to this was the contract workers from Vietnam who did come to work, as the result of a state-to-state agreement in the latter years of the GDR.)

Disappointing and puzzling is that Hoyer offers little space to discuss the process of change in the GDR which eventually led to reunification—in particular the blatant interference and then domination by the FRG which impacted decisively on the last GDR elections in 1990. Even more serious is the cursory description of the involvement of the Trust Agency (Treuhand) in effectively destroying the GDR’s infrastructure. And here, Hoyer gets it wrong: The Treuhand was formed in February 1990, with the stated aim of seeking a way to share publicly-owned properties among the citizens of the GDR. After the elections (when the GDR was still a separate state), a West German businessman was appointed as chair of the Treuhand and changed its task to become the privatization vehicle for all publicly-owned property, with most of those, formerly state- or publicly-owned enterprises sold off for a song, in the main, to West Germans.

Hoyer also devotes only a very short section (compared with the detailed descriptions in the first 100 pages of the violent history that predated the birth and beginning of the GDR) to describe the turbulent months that led to reunification. In the end, East Germans found themselves co-opted into an existing federal German state while at the same time their experiences, lives, and work were ignored, denied, and snubbed, leading to the feeling on the part of many former GDR residents of becoming second-class citizens in the new Germany.

This book portrays the 40 years of the GDR as a history of a dictatorship, a police state where threats and arrests were normal everyday occurrences. It gives the impression that this was a totalitarian system through and through, in which only two men (Ulbricht and later Honecker) wielded decisive power. By concentrating on Ulbricht and Honecker, the author gives the reader the impression that building socialism was their idea, their project, and no one else’s. She ignores the many anti-fascists who had returned from exile (both West and East) and were keen to build socialism on German soil as a reaction to what they had experienced under Hitler. On the positive side, however, Hoyer does—unlike almost all previous histories—portray the GDR as a country in a process of change, rather than as a nation fixed in a static, immediate postwar time warp.

As she says, the GDR has been written out of the national narrative of Germany, and she emphasizes that it “deserves a history that…gives it its proper place.” I just wished that more positive aspects had been covered to help readers understand why so many in the East still today treasure their past. On that note, it is instructive to recall that even after unification, almost a third of East Germans voted for the PDS (Party of Democratic Socialism), the successor party of the ruling SED (Socialist Unity Party). And, if anyone looks at the Facebook page of the group, DDR—ich war dabei! (The GDR—I was there!), they will see so many posts and comments from former GDR citizens who clearly look back on their lives in that country as rewarding and pleasurable.

One small, but amusing mistake in Hoyer’s book is that she mentions the anniversary of the establishment of the GDR as Oct. 3, but it was Oct. 7. Oct. 3rd is now designated the “Day of German Unity,” and it was purposely chosen back in 1990 to obviate the commemoration of yet another anniversary of the GDR.

Katja Hoyer

Beyond the Wall: A History of East Germany

Basic Books, 2023

496 pp.

ISBN: 1541602587, 9781541602588

————————

We hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, please support great working-class and pro-people journalism by donating to People’s World.

We are not neutral. Our mission is to be a voice for truth, democracy, the environment, and socialism. We believe in people before profits. So, we take sides. Yours!

We are part of the pro-democracy media contesting the vast right-wing media propaganda ecosystem brainwashing tens of millions and putting democracy at risk.

Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader supported. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all.

But we need your help. It takes money—a lot of it—to produce and cover unique stories you see in our pages. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today.