MINNEAPOLIS—The consensus among activists speaking at a recent press conference in Minneapolis is that it will take massive street protests to convict Derek Chauvin for the murder of George Floyd.

Frank Chapman, a spokesperson for the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression, which was founded in 1973, pointed to the national significance of the trial in a recent Facebook post: “This trial is not only important for Minnesota, which has never seen a white police officer prosecuted for murdering a Black person. It is important for the entire country, which was set aflame in rebellion after Floyd’s murder. We will not rest until we see all four of George Floyd’s killers taken off the streets, and our communities have the power to decide who polices our communities and how our communities are policed.”

In Minnesota, since 2000, there have been 405 documented cases where Minnesotans have been killed by law enforcement, including four people since the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020. Many were Black, brown, Asian, and Native lives. That Derek Chauvin is the first white police officer to be tried in Minnesota for the murder of a Black man is both a victory and an indictment of political and civic leaders at all levels for their failure to hold law enforcement accountable. Protesters in Minnesota and around the nation, however, are determined that Chauvin will be the first white officer imprisoned.

“DFL on trial”

Since 1979, Minneapolis city government has been headed by a Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party mayor and a majority DFL city council. It is fair to say, then, that the failure to deal with police violence within the Minneapolis Police Department (MPD) lies squarely with the DFL Party. The DFL leadership has presided over a police disciplinary system where only 1% of thousands of complaints against police have been adjudicated, according to Communities United Against Police Brutality (CUAPB), which tracks complaints against the MPD. Due to this lack of oversight, since 2003 city taxpayers have paid $45 million in civil judgments resulting from MPD officers accused of harassment, assault, and wrongful death.

This political failure under DFL governance means that in the background of the Chauvin case, “the DFL is on trial,” said August Nimtz, a political science professor at the University of Minnesota and a well-known leader of the solidarity movement with Cuba. Dave Bicking of CUABP echoed Nimtz’s charge, adding that the inability of the city to stem police violence also implicates the city’s business, banking, and real estate interests that play a key, if not a decisive role in city politics.

Who is Derek Chauvin?

He is like too many officers in law enforcement agencies across the nation. Chauvin is a product of a regime of recruiting, hiring, and training that reproduces officers like him decade after decade. A system that is run by state boards and administrative units, like those in Minnesota, whose members are largely comprised of law enforcement personnel. A system overseen by state legislators that are often complicit in authoring and passing laws that in effect harbor the likes of Chauvin. Thus in Minnesota, like in other states, cops train, hire, supervise, and investigate their own.

Chauvin’s record of brutality reads like an indictment. In 2006, he was involved in the shooting and killing of Wayne Reyes, and in 2008, he shot and seriously injured Ira Latrell Toles. Despite his egregious record of complaints and misconduct over his 19-year tenure, Chauvin received two medals of valor for his police work.

Given this lack of accountability, Chauvin could reasonably assume as he pressed his knee into Floyd’s neck for more than nine minutes that he would not face justice, even if Floyd died. In broad daylight, knowing he was being filmed, Chauvin did not blink an eye. He dared someone to intervene. Chauvin, as many here in the African-American community have witnessed repeatedly, was also doing his job—training two new recruits assigned to him on how to treat Black people.

Defense strategy vs. the people’s protest

The state statute typically cited by county attorneys for not indicting an officer for using deadly force is not applicable in Chauvin’s case. Statute 609.066 applies to incidents where an “objectively reasonable officer would believe” that they or a fellow officer is in imminent danger. Clearly, however, as seen in the video of Floyd pleading for his life, neither Chauvin nor the other three officers were in imminent danger.

This begs the question on what legal grounds the defense might argue Chauvin’s case. According to material gleaned from media reports and from motions filed by Chauvin’s defense attorney, they are likely to present medical evidence that Floyd died of a drug overdose and not due to restraints applied by the officers. Chauvin’s attorneys will also attempt to influence the jury by slandering Floyd’s character based on his past legal and drug problems.

David Schultz, a visiting professor at the University of Minnesota Law School, said in an email exchange that recent case history shows “it is difficult to secure police convictions…. The law favors them.” Schultz also noted that although to many people the video of Chauvin pressing his knee into Floyd’s neck is irrefutable evidence of guilt, “it proves only part of the requirements to show someone is guilty of a crime.” The law, as he said in a 2015 article, “has tipped too far in favor of police.”

Reforms or revolutionary demand?

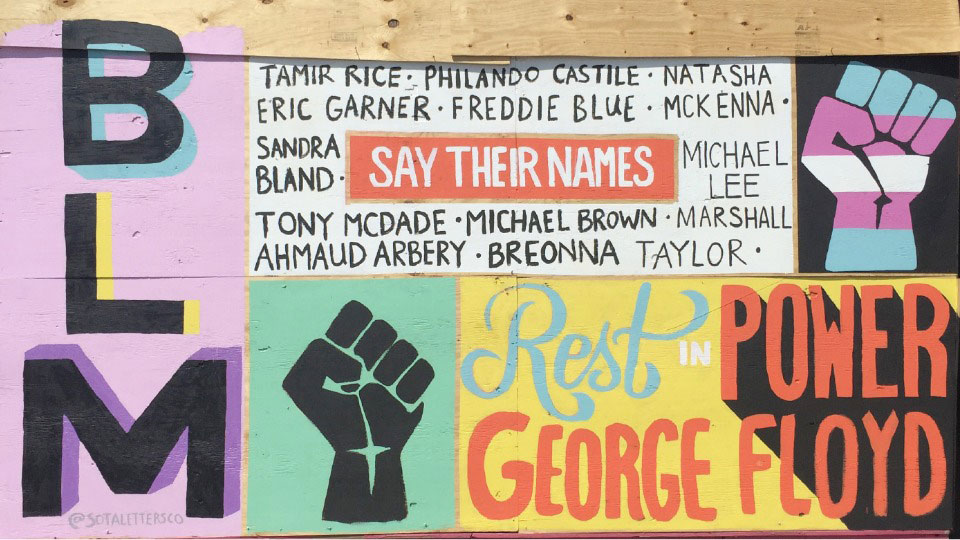

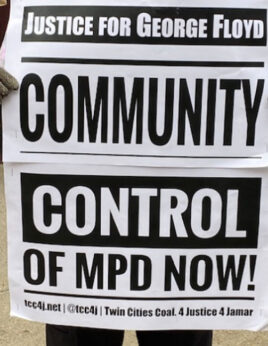

So long as the current hiring and administrative processes remain in place, there will be more George Floyds. Decades of reforms have clearly failed to stem the violence. A solution articulated by African-American leaders in the 1960s is community control of police—an idea that is in everyone’s interests.

At that time, and in today’s context, it is akin to a revolutionary demand. Community control means citizens, not police administrators alone, would oversee the hiring, discipline, and evaluation of law enforcement officers. Police and community members will surely need to work together, but the community, not police, would have the final say.

In Chicago and other cities, activists are organizing citizen support for a model called the Civilian Police Accountability Council (CPAC), or a commission, as it is called in Minneapolis. After decades of reforms that have clearly failed to end police violence and have even failed to reduce crime, CPAC is becoming a marker around which a more militant struggle is arising.

Legislation proposed in Minneapolis would give residents decision-making authority regarding law enforcement policies, budgets, and disciplinary actions. The democratic principle underlying CPAC is that the people who live in a community should decide how policing is conducted and who serves. A step toward building the people power to win community control is to convict officers like Chauvin and to force law enforcement agencies to purge racist cops and those with records of brutality.

Is it possible to reform the police? What does it take to stop police violence? Professor Nimtz, in an interview, answered by pointing to his June 2020 article “Why there are no George Floyds in Cuba.” In Cuba, as Nimtz notes in the article, a person cannot become a police officer without being vetted by the community they will serve. Such vetting is the core demand underlying CPAC.

Historical view

According to Nimtz, the Chauvin trial is the most high-profile police brutality case since Rodney King was assaulted and beaten by Los Angeles police officers in 1992. It was the first time police brutality was filmed and broadcast on national television. Lest we forget, he added, “It pains me to think about all the murders that did not get captured on camera.”

“In the African American community, we always knew about it, but you couldn’t convince anyone that this was actually happening,” Nimtz said. That changed with King, and the period from that moment up to the murder of George Floyd marks the era of the contemporary struggle against police brutality.

Because people rose up in the streets, the system was forced to indict Chauvin and the other three cops. “This is why Chauvin is on trial,” Nimtz said. The uprising showed the power of applying pressure on the system from outside, instead of having faith in a justice system that is beholden to laws that protect the police.

“Don’t ever confuse the law with justice,” Nimtz added. “In the U.S. so-called criminal justice system, cops don’t get indicted, they don’t go to jail.”

Thus, “If we can convict these cops, that would be an important step. That’s the only way to break the code of silence.”

Comments