On this date 190 years ago, in 1825, the Erie Canal, first major man-made waterway in the U.S., was opened, providing a navigable water route from Buffalo, on Lake Erie, across New York State to Albany on the Hudson River, which feeds into the Atlantic Ocean. All along the route cannons were fired and celebrations were held for the opening.

Construction of the 363-mile-long canal started on July 4, 1817, and eventually cost $7,602,000. Before railroads flourished, the Erie Canal enabled both farm and industrial products from the quickly growing Midwestern states to reach markets on the East Coast and abroad. The canal also facilitated internal migration of population westward.

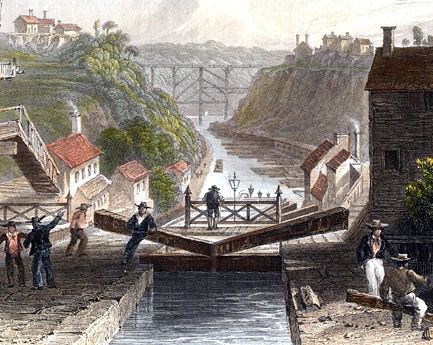

East to west, from the Hudson to Lake Erie, the land rises about 600 feet. Locks could handle up to 12 feet, so even with the heftiest cuttings and viaducts, at least 50 locks would be required. Such a canal would be expensive to build even with modern technology; in 1800, the expense was barely imaginable. Pres. Thomas Jefferson called the idea “a little short of madness” and rejected it; however, New York Governor DeWitt Clinton became interested in the project. The opposition ridiculed the project as “Clinton’s folly” and “Clinton’s ditch.” In 1817, though, Clinton received approval from the legislature for $7 million for construction.

Canal workers cut the channel 40 feet wide and 4 feet deep. They piled removed soil on the downhill side to form a walkway known as a towpath, and some of it provided landfill for New York City.

Its construction, through limestone and mountains, proved arduous and daunting for the canal workers. Construction used some of the most advanced engineering technology from Holland. The stonework was accomplished hundreds of immigrant German masons, who later built many of New York City’s buildings. All labor on the canal depended upon human and animal power and the force of water. As the canal progressed, the crews and engineers working on the project developed expertise and became a skilled labor force.

The men who planned and oversaw construction were novices, both as surveyors and as engineers. There were no civil engineers in the U.S. then. But despite their inexperience, they overcame each technical obstacle and produced a perfectly working design. According to planners, using an earth scraper and a plow, a three-man team with oxen, horses, and mules could build a mile in a year.

Increased immigration filled the need for labor: many of those working on the canal had recently come to the States from Ireland. Construction continued at an increased rate as new workers arrived.

The workers lived on the edge of subsistence financially; physically, canal work was back breaking, dangerous, and at certain times fraught with the near certainty of cholera and malaria, which carried off sizable chunks of the work force during virulent years.

In 1824, before the canal was completed, a detailed Pocket Guide for the Tourist and Traveler, Along the Line of the Canals, and the Interior Commerce of the State of New York, was published for the benefit of travelers and land speculators.

Once the entire canal was officially open, a flotilla of boats led by Gov. Clinton aboard the Seneca Chief sailed from Buffalo to New York City in ten days. Clinton ceremonially poured Lake Erie water into New York Harbor to mark the “Wedding of the Waters.” On its return trip, the Seneca Chief brought a keg of Atlantic Ocean water back to Buffalo to be poured into Lake Erie by Buffalo’s Judge Samuel Wilkeson, who would later become mayor.

The Erie Canal was acclaimed as an engineering marvel that united the country and helped New York City to become a financial and trade capital. The port of New York became essentially the Atlantic home port for all of the Midwest. Because of this vital connection, and later the railroads, New York would become known as the “Empire State.” At the western end, Buffalo grew from just 200 settlers in 1820 to more than 18,000 people by 1840.

As the canal brought travelers to New York City, it took business away from other ports such as Philadelphia and Baltimore. Those cities and their states started projects to compete with the Erie Canal. In Pennsylvania, the Main Line of Public Works was a combined canal and railroad running west from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh on the Ohio River, opened in 1834.

On Jan. 28 and 29, in 1834, Andrew Jackson became the first president to use federal troops against protesting workers. The workers were protesting not just their low pay but also the intolerable working conditions on an important canal construction project.

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal was intended to facilitate the shipping of goods from the Chesapeake Bay to the Ohio River Valley.

In 1842 a continuous rail line (which later became the New York Central Railroad) opened the whole way to Buffalo and provided for faster travel. Yet as late as 1852, the canal carried 13 times more freight tonnage than all the railroads in New York State combined, and continued to compete well with the railroads until the beginning of the 20th century.

The canal helped bind the still-new nation closer to Britain and Europe, as Midwestern wheat flowed to the Old World. Concern that erosion caused by logging in the Adirondacks could silt up the canal contributed to the creation of a New York National Historic Landmark, Adirondack Park, in 1885.

Many folk tales and songs were written about life on the canal, as well as writings by well-known authors. The popular 1905 song “Low Bridge” by Thomas S. Allen memorializes the canal’s early heyday, when barges were pulled by mules rather than engines.

The late environmentalist Virginia Warner Brodine wrote the novel “Seed of the Fire” (International Publishers NY) based on the actual struggles of Irish immigrants and other workers in the canal camps of Ohio in the 1820s.

A 36-mile stretch of the old canal is preserved by New York State as Old Erie Canal State Historic Park. In 1960 the Schoharie Crossing State Historic Site, a section of the canal in Montgomery County, was one of the first sites recognized as a National Historic Landmark.

Sources: Chase’s Calendar of Events, Wikipedia.

Photo: View east of eastbound Lockport on the Erie Canal by W.H. Bartlett, 1839; cropped by Beyond My Ken. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons.

Comments