The Great Depression was among the most spectacular failures of capitalism. The unprecedented and unregulated expansion of corporate greed during the roaring 1920s led to the creation of several mass monopolies on a scale never seen in human history. The stock market expanded exponentially into previously quiet Main Street economies. Smaller hometown hospitals and schools were bought out and controlled by profit-seeking carpetbaggers. Millions of people who had previously known little about Wall Street began to see this capitalist invention as their monetary salvation.

It wasn’t long before the Depression reduced gross domestic product by a frightening 30% and industrial production by an even more staggering 47%. By comparison, the GDP reduction during the 2007-09 Great Recession was 4.3%. The unemployment rate in 1933 peaked at 24.9%. Shanty towns, coined “Hoovervilles” after the failed Republican president, appeared in cities and towns across America. The worldwide economy crumbled and brought the working class down with it.

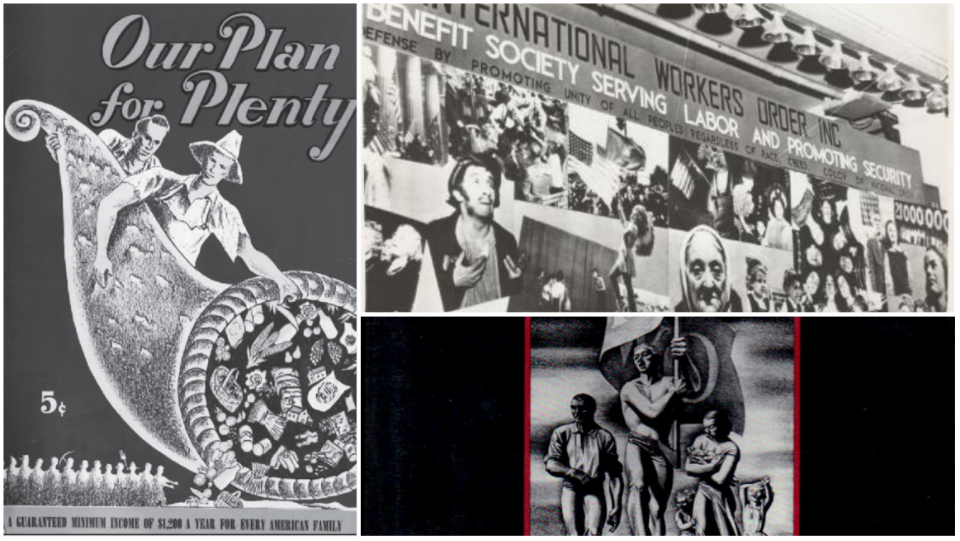

Largely in response to the Great Depression, multitudes of fraternal, religious, and mutual aid societies were chartered. Already existing organizations were quickly filled with new members and ideas. One existing Jewish fraternal organization, the Workmen’s Circle, officially split due to increased infighting and ideological differences. The more radical portion of the WC voted to form a new mutual aid society named the International Workers Order. Only a year after its founding, a leader and publisher with the IWO described the organization as a “class struggle” society with “communist party activism.”

Later, this same leader would go further by stating that “the IWO must look upon the Communist Party as the only labor party in the United States.” IWO lodges would also openly advertise and solicit subscriptions to the CP’s Daily Worker newspaper. While the IWO largely endorsed the CP’s program, the organization was careful to accept any worker regardless of political preference. Further, the IWO would take extensive precautions to ensure that collected funds were never used for CP purposes.

The IWO’s radical politics wasn’t the only thing to make the mutual aid society unique. It was the first healthcare service provider where any individual, regardless of race, status, gender, or religion, could receive equal benefits. The idea that a Black woman and a white man could receive the same benefits and services at the same cost was perhaps one of the most radical features of the IWO.

Pecola Moore, an African American woman and member of the IWO, said about the organization: “Being an American Negro (so-called), I have been helped beyond words to tell. The fellowship of help through the fraternity and sick benefits is a blessing to the poor and distressed persons. I would not have been able to pay a doctor, nor buy the medicines, to say nothing of paying for a home call from a physician, had it not been for the help of this organization.”

Moore would go on to say that her main attraction to the IWO wasn’t the benefits though: “What I liked best about the Order was the fact that it really practices brotherhood and democracy. The Brothers and Sisters in my Lodge hold picnics, socials, lectures, and many kinds of educational activities, and all persons of all creeds and races are together in perfect unity. My lodge has on many occasions fought for issues important to the Negro people…each year we celebrate Negro History Week with wonderful programs.”

Another African American member of the IWO put it simply: “No Jim Crow in the IWO.” One author noted that such equal treatment encouraged an equally powerful fight towards universal justice: “The IWO was one of the few organizations in which Jewish, Slavic and Italian Catholic, Hispanic, African American (including Black Muslim), and Arabic leftists worked side by side in pursuit of racial and workplace justice.”

At a time when birth control was still criminalized as a type of “pornography,” the IWO was among the first, and by far the cheapest, places for working-class women to access such aid. The birth control section of the organization became so popular that the New York Medical Department stated that the IWO was “operating a Birth Control Center in the interests of the membership of IWO and all of their friends…[and the] Birth Control Center is one of the finest and best equipped.” This birth center was attuned to the needs of the working class in various ways. As one example, the center was always open late enough in the evenings for working-class women to be able to visit without missing a precious workday.

As could be imagined, such an open and equitable society attracted masses of the working class from every background, race, and gender. Non-Marxists and non-CP members were quickly becoming the majority within the society. For example, at Philadelphia’s opening convention of the IWO, not a single person in attendance was a CP member. Among West Virginia mining towns, IWO leadership noted that they were “building branches of all nationalities,” without worrying over party preference. In Los Angeles, IWO organizers were creating whole Japanese and Spanish lodges without a single CP member.

By 1947—the same year the IWO was placed on the U.S. Attorney General’s list of subversive organizations—the IWO had successfully reached 180,000 members. The IWO found that while many joined the organization with limited working-class consciousness, they soon developed an enthusiastic attitude towards the IWO’s broader ideological initiatives.

It’s clear that the IWO became successful at organizing because it implemented much-needed mutual aid for the working class. This idea has been practiced more recently, too. The Amazon Labor Union organized thousands by offering aid that warehouse workers and their families desperately needed. The Los Angeles County Federation of Labor created a massive mutual aid initiative, coined the “People’s Project,” aimed at organizing nearly two million people. A New York gig-worker organization’s “strategic power” has come “from focusing on mutual aid as a method to build community.” Mutual aid was also effective in responding to a capitalist-induced housing fire and attracting working-class election candidates. Although on a different scale, these examples prove that mutual aid is still successful in organizing and growing the fightback against various capitalist incursions.

Across the United States, the working class is in dire need. When compared with the last 30 years, the purchasing power of workers’ wages is collapsing faster than ever. Nearly 30% of Americans making less than $50,000 had their entire savings destroyed due to the COVID-19 crisis. Workers’ wages are continually failing to keep up with the rapid pace of inflation. Furthermore, because the working class makes up less than 10% of city councils, 3% of state legislatures, and 2% of Congress, workers cannot depend on aid from the top.

For the working-class movement to best organize and thrive, it’s necessary for the powerful potential of mutual aid to be fully realized. Only then can mutual aid become both a short-term economic solution for workers and a long-term organizing tool in building a mass labor movement open to all.

To learn more about the IWO and its history, read: A ROAD TO PEACE AND FREEDOM: The International Workers Order and the Struggle for Economic Justice and Civil Rights, 1930–1954 by Robert M. Zecker.

As with many news analytical and op-ed articles published by People’s World, this article reflects the opinions of its author.

Comments